Reach for the Stars: The perils of being a 90s pop star

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBlame the Spice Girls.

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw an explosion of sugary, lightweight pop music, as record labels realised there was a market for something other than dreary indie bands with haircuts as dishevelled as their clothes.

Steps, Westlife, B*Witched, 5ive, S Club 7, Busted and Atomic Kitten topped the charts and sold out arenas with songs that captured the giddy inertia of teenagedom: Don't Stop Movin', Keep On Movin', Rollercoaster, Flying Without Wings.

In the pages of Smash Hits and Top of the Pops magazine, these bands seemed improbably glamorous. Then along came Michael Cragg to dispel the myths.

His new book, Reach For The Stars, is a history of British pop from 1996 to 2006 that lays bare the "mechanisms behind the manufactured pop juggernaut".

It's a story of exploitation, exhaustion and even fist fights.

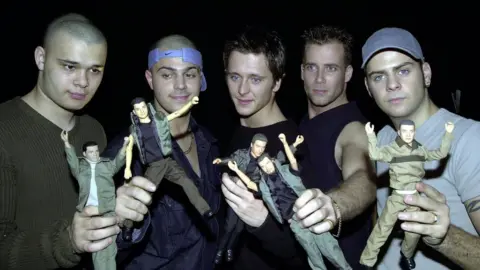

Claire Richards from Steps recalls "starving myself for four-and-a-half years because I was told I had to lose weight on day one". Sugababe Mutya Buena was granted two weeks maternity leave before being shoved back "in the studio, breastfeeding at 5am". The boyband 5ive went from sharing a house to outright animosity in the space of 12 months.

"There were fist fights that spilled out into corridors," admits singer Ritchie Neville.

"The hours were brutal, and the schedule like no other," adds Hear'Say's Myleene Klass. "No rock stars would be able to keep up. It's hardcore."

PA Media

PA MediaAnd when it all ended, the fallout was extreme.

"Not knowing what was next was a huge shock," says S Club 7's Jo O'Meara.

"[S Club] was so military and then it stopped so quickly. We were told what to do, told where to go, told when I'm eating. I didn't know how to be without it."

One For Sorrow

Cragg, who has written for Vogue, GQ and The Guardian, spoke to more than 100 people for his book, uncovering scores of previously untold stories.

"I wanted to ask questions they weren't really asked at the time, when they were more likely to be asked what their favourite sandwich filling was," he says.

He discovered an industry that put "punishing" expectations on singers who'd barely left school.

"They were governed by the charts. If you didn't make the top five, it was like 'This is not enough.'

"I think now, people would be doing backflips if their debut single got to number eight, but back then there was a lot of money being spent, so the rewards had to be really high and quick."

Not that bands necessarily saw any of those rewards.

Sugababes' Keisha Buchanan reveals that she "got transferred £3,000" after the band signed "a million-pound deal".

"Even when the money was coming in," adds 5ive's Scott Robinson, "we were given £100 a week".

PA Media

PA MediaThere was one exception, says Cragg, in the form of line-dancing pop behemoth Steps.

"They'd all been [Butlins] Redcoats or had other jobs, so they understood what was going on a tiny bit more," he says.

"They knew that if they went to America to support Britney Spears, that the money would be coming out of their budget, so they were reluctant to do it at first.

"And that's interesting because most other people would have (a) been told they had to do it or (b) would have jumped at the chance and not thought about the finances. But Steps were a slight anomaly."

Sound of the Underground

Although his book is presented as an oral history, Cragg's knowledge and affection for the music shines through every paragraph.

That's how he manages to unearth the real reason 5ive didn't get to record Baby... One More Time (they confidently told songwriter Max Martin it was awful), and to explain why the public turned against the original reality TV band Hear'Say.

"Popstars was done as a documentary, and people were incredibly upset when they launched as a band because they'd had a tiny makeover," he says.

"Suzanne got hair extensions and everyone was like, 'Oh my God, who she thinks she is?'"

PA Media

PA MediaRevisiting this decade-long flourish of British pop was more than just an academic exercise, however.

At the time, Cragg was a "closeted teenager" who hid his love of pop music behind a veneer of indie cool. In the opening prologue, he recounts making a pilgrimage to Dublin to see Scottish rockers Travis when, really, he wanted to gorge himself on Spice Girls memorabilia.

"I actually won those tickets," he says. "I entered a competition and I won and I took my friend and we stayed in a youth hostel where I got hit by an inflatable armchair.

"It's such a dark time in my life. I was hiding away from this music because I thought it revealed too much of me."

Writing the book was the first time he was able to "look back at the music [and] be happy to embrace it fully. And that was quite exciting."

Cragg showed an early interest in journalism. As a child, he'd watch the TV news and write down the details. In the era of MySpace, he started blogging music reviews, then took a job selling adverts for The Guardian, where he eventually plucked up the courage to pitch a festival review.

"It just sort of rolled from there," he says, reminiscing about his first ever interview, with Texas rock band Midlake, "one of whom was asleep".

"I was overly-prepared. I had 14 pages of questions and I literally sat there and read them out. It was not ideal."

Since then, he's honed his technique on everyone from Lady Gaga and Katy Perry to Miley Cyrus and Britney Spears.

"Once I started writing about pop music, I guess I jumped out of the closet," he laughs.

Nine Eight Books

Nine Eight BooksOver the course of his career, the gravitational centre of music writing has shifted from glossy magazines to broadsheet newspapers, resulting in more serious-minded coverage. Nowadays, stars like Billie Eilish and Dua Lipa expected to have opinions on war and mental health and LGBTQ rights, instead of declaring their favourite colour.

Our conversation takes a long detour into the merits of this approach. Has the press stripped pop music of its glamour? Or did old-school magazines do 5ive and Sugababes a disservice by papering over the mental health crises that forced their founding members to quit?

"I think the mental health situation with those bands was the responsibility of the record labels and the people around them, not the journalists who were trying to sell this fun pop era to fans," Cragg says.

"These days, if you're going to be on the cover of a broadsheet supplement, there's definitely a pressure to talk about these incredibly large and heavy issues - but if you go into an interview with Charli XCX and you talk about her mental health, is that helping Charli XCX, necessarily?

"Charli XCX is incredible. She's hilarious. She makes absolutely bonkers music. I want to know about that. I want to know, like, if I came around for dinner, what would she cook me? I think that's more interesting, as a fan."

As a result, Cragg insisted his book didn't just present the "sad stories" of pop.

"Even 5ive, whose career ended horribly when they were at their peak, have come to a place of acceptance and are able to look back on it fondly."

With S Club 7, Busted and Sugababes all on the comeback trail, the book arrives with auspicious timing. Unless, that is, you're Louis Walsh, who gave Cragg an unforgettable pull-quote for the dust jacket.

"Nobody buys books. No-one's going to read this."

Reach for the Stars: 1996-2006: Fame, Fallout and Pop's Final Party by Michael Cragg is published on 30 March.