Venice Biennale: Ukrainian art exhibition opens in shadow of war

EPA

EPAOn Thursday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky opened an exhibition about defending his country's freedom at the Venice Biennale festival.

Speaking via video link, he said "art can tell the world things that cannot be shared otherwise".

His country's culture is a focus of attention in Venice and artworks have been escorted out of Ukraine by police.

In contrast, the Russian Pavilion stood locked and empty; a sign of the country's isolation.

President Zelensky described the pain of war as he addressed the world's oldest and most prestigious contemporary art exhibition earlier this week.

He offered examples of Ukrainian soldiers finding murdered civilians in Bucha, of medics rescuing injured people in Kharkiv, and of a girl writing a letter to her mother who died in Mariopul as experiences that can be best reflected in art, "because this is about something beyond words".

As he talked of his country's fight for freedom, he said: "There are no tyrannies that would not try to limit art. Because they can see the power of art. It is art that conveys feelings."

Jack Garland

Jack GarlandUkraine's art is taking centre stage at the Venice Biennale, which has made a space at the heart of the Giardini for what is effectively a temporary pavilion for Ukraine.

There is a pile of sandbags, mirroring the sandbags being used in Ukraine to protect artworks, and a scorched structure covered in posters of war-related art work.

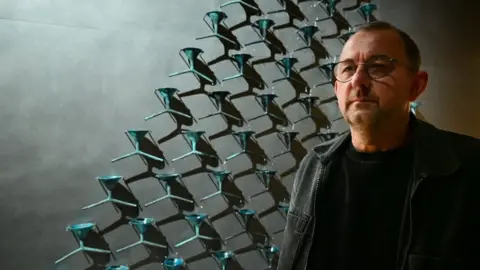

The official Ukrainian Pavilion in the nearby Arsenale shows a work by artist Pavlo Makov that nearly didn't make it to Venice.

Called The Fountain of Exhaustion, it's a series of funnels arranged in a triangle through which water drips and divides. Makov described it to me as a metaphor for "the exhaustion of humanity, the exhaustion of democracy".

Vincenzo Pinto/Getty

Vincenzo Pinto/GettyOn the day the Russians invaded, with air raid sirens blaring and shelling starting, co-curator Maria Lanko loaded the funnels into the boot of her car and began the long journey out of Ukraine to Venice. Lanko told me "leaving Kiev was very scary because you could see the fires on the outskirts after the shelling. That was the scariest".

At that point it was unclear if Makov would be joining her in Venice. He lives in Kharkiv, one of the places to come under early Russian assault. He spent time in shelters after "really intensive bombing of the city", he says, before leaving with his 92-year-old mother and other family members "under missile attack... We put five of us in my car, and we just left the city".

Makov is 63. The younger male co-curators of his exhibition had to get special dispensation from the Ukrainian Government to leave the country temporarily to attend the Biennale.

The fact they were allowed to - when all men between 18 and 60 are forbidden from leaving - is a sign of the importance the Ukrainian authorities place on cultural representation. In Venice, as journalists from across the world queued to interview them, both Makov and Lanko talked of being cultural ambassadors.

Vincenzo Pinto/Getty

Vincenzo Pinto/GettyThey are no longer representing their art as individuals; they are representing a country whose culture is under threat.

Makov told me the Russians are continuing what they have tried to do for centuries. "They want to level and demolish Ukrainian culture totally because Ukraine doesn't exist, it's part of Russia," he says. "They say it openly. The war is a punishment."

At the Zelensky-endorsed exhibition called This is Ukraine: Defending Freedom, I watched Ukrainian artworks being unwrapped by the likes of Maria Primachenko, who has become a symbol of the country's national identity, as well as a beautiful 17th Century icon of the Virgin Mary, believed to be by Stefan Medytsky.

These works were transported from Ukraine under police guard. They are now totems for a country that fears its culture will be wiped out.

Jack Garland

Jack GarlandMeanwhile, the Russian Pavilion is shut and empty. The curator and artists who were due to exhibit their work in Venice this year pulled out when the invasion started.

The only thing to see when I passed by was a protester, another Russian artist, Vadim Zakharov, who unfolded a poster denouncing the war.

In 2013, Zakharov represented his country at its Biennale pavilion. Now he berates Russia for its "propaganda" and the "murder of women, children, people of Ukraine".

Jack Garland

Jack GarlandHe was applauded by some people who stopped to watch. Soon the Italian police arrived and his poster was removed, a far better fate than has befallen artists and other anti-war protesters in Russia. "If I was in Red Square," he said, "it would be different."

At a time when they are fighting at home, Ukrainian art is taking on special significance in Venice. But Makov told me he finds it almost impossible to think of creating new work after what he witnessed in Kharkiv.

He referenced the famous anti-war painting by Picasso, created after the bombing by the Nazis and Italian Fascists of the Basque town of Guernica in 1937.

Carlos Alvarez

Carlos AlvarezMakov told me that if Picasso had actually been in Guernica during the bombing, he might not have been able to paint the picture. "Some artists can, but for me, it's very difficult," he says.

"Art is an important piece of life, it helps us to create and maintain our culture. But I heard this explosion, I saw the destroyed centre of Kharkiv. You know, art is a modest thing, because the drama of life is always bigger."

As his country fights for its survival, though, Ukrainian works here in Venice have a role to play in revealing the richness of Ukraine's culture, and what there is to lose.