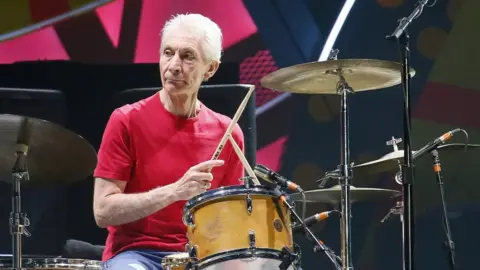

Charlie Watts: The subtle magnificence of the Rolling Stones' drummer

Reuters

ReutersOne night in 1984, Mick Jagger made a mistake.

Worse for wear in an Amsterdam hotel, the Rolling Stones frontman phoned up Charlie Watts' room and demanded, "Where's my drummer?"

Twenty minutes later, Watts appeared at his door, dressed to the nines in a Savile Row suit, clean-shaven and wearing cologne. "Never call me your drummer again," he told Jagger. "You're my singer."

According to Keith Richards' 2010 memoir, Watts then hauled Jagger up by the lapels "and gave him a right hook".

"Mick fell back onto a silver platter of smoked salmon on the table and began to slide towards the open window and the canal below it."

It was a rare display of emotion from the usually unshakeable drummer, who shunned the flamboyant, showbiz lifestyle of his colleagues.

Even when he succumbed to drug addiction in the mid-80s, Watts handled it with characteristic poise - ditching all of his vices in one go, after breaking his ankle retrieving a bottle from his wine cellar.

"I happened to be booked for a jazz show at Ronnie Scott's in six weeks' time, and it really brought it home to me how far down I'd gone," he told The Guardian in 2000. "I just stopped everything - drinking, smoking, taking drugs, everything, all at once. I just thought, 'enough is enough.'"

He was equally stoic about his success with The Rolling Stones - which he once described as "five years of work and 20 years of hanging around".

But Watts' contribution to the band was vital. His jazz-inflected swing gave the Stones' songs their swagger, pushing and pulling at the groove, and creating room for Jagger's lascivious drawl.

On tracks like Honky Tonk Women and Brown Sugar, he created some of rock's strongest grooves, and the isolated drum track from Gimme Shelter is a masterclass in timekeeping and musicality.

"As much as Mick's voice and Keith's guitar, Charlie Watts's snare sound is the Rolling Stones," Bruce Springsteen once wrote. "When Mick sings, 'It's only rock 'n' roll but I like it,' Charlie's in back showing you why!"

As the world absorbs the sad news of his death at the age of 80, here are some of his best moments from The Stones' back catalogue.

1) Get Off Of My Cloud

Allow Google YouTube content?

Watts was never the most flashy drummer - but his propulsive strength is the backbone of Get Off Of My Cloud, The Stones' fifth consecutive UK number one single.

He opens the song with a rock-solid beat-and-fill pattern, that he basically repeats for three straight minutes without ever letting up. It's a feat of endurance that keeps the song in perpetual, thrilling motion.

2) Honky Tonk Women

Allow Google YouTube content?

In his youth, Watts dreamt of being a jazz drummer, but he never saw a big distinction between his first love, and the rock music that made him famous.

"What is jazz?" he asked Modern Drummer magazine in 1981. "Originally, it was primarily dance music. Rock and roll is dance music."

His slinky, cowbell-driven groove on 1969's Honky Tonk Women is one of Watts most danceable drum tracks. He even pushes the tempo up in the final chorus to really set the dancefloor on fire.

Interestingly, the cowbell itself isn't played by Watts but by the Stones' producer Jimmy Miller - and the band could never replicate his slightly stumbled intro in concert.

"We've never played an intro to Honky Tonk Women live the way it is on the record," Watts said in the book According to the Rolling Stones.

"That's Jimmy playing the cowbell and either he comes in wrong or I come in wrong - but Keith comes in right which makes the whole thing right. It's one of those things that musicologists could sit around analysing for years. It's actually a mistake but from my point of view it works."

3) Paint It, Black

Allow Google YouTube content?

The best Rolling Stones songs have a viscous streak of darkness, and Paint It, Black is among their darkest.

Jagger's lyrics depict the abject grief of a man who has suddenly and unexpectedly lost his partner - his hopelessness amplified by the haunting sitar line and Bill Wyman's Hammond Organ chords.

In response, Watts pitches his drums low, rattling the floor tom with a pounding 4/4 beat that gives the song a sinister, eerie undercurrent.

4) Sympathy For The Devil

Allow Google YouTube content?

Originally written as a folk ballad in the style of Bob Dylan, Sympathy For The Devil went through six different rhythms as The Stones tried to figure out the best setting for the song.

"It was all night doing it one way," Watts later recalled, "then another full night trying it another way, and we just could not get it right. It would never fit a regular rhythm."

They eventually settled on an Afro-Brazilian samba groove known as Candomblé. Rocky Dijon played congas, while Bill Wyman added an African shekere - but it was Watts' Latin jazz-flavoured beat that gave Sympathy its Satanic heat.

Jagger later singled out the rhythm track for its "tremendous hypnotic power".

"But it has also got some other suggestions in it," he added, "an undercurrent of being primitive - because it is a primitive African, South American, Afro-whatever-you-call-that rhythm (candomblé). So to white people, it has a very sinister thing about it."

5) 19th Nervous Breakdown

Allow Google YouTube content?

The Stones are firing on all cylinders on this 1966 single, from Mick Jagger's vituperative lyrics to Brian Jones' hypnotic, Bo Diddley-inspired bass riff.

Underpinning it all is Watts, with one of his most manic drumbeats, full of jittery ride cymbals and rumbling tom fills.

The beat bounces discontentedly around in weird, tense manner that mirrors the fractured mental state of the song's subject - a "spoiled brat" whose material wealth can't make her (or Jagger) happy.

Further listening

Follow us on Facebook, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected].