Night Fever: How club culture has moved with the times

Shutterstock

ShutterstockFrom the Swinging 60s to the age of digital technology, a new show at the V&A Dundee looks at how club design around the world has evolved to reflect the ever-changing music we've danced to over the decades.

Playing on an endless loop in the middle of the V&A exhibition Night Fever is a 40-second clip of John Travolta's famous moves to the Bee Gees' disco classic You Should Be Dancing.

The scene from the film Saturday Night Fever is now 44 years old, but it remains a crucial moment in the history of nightclubs and discotheques. Pre-social media, and before Strictly and the other TV dance contests, the film made disco music and disco dance part of mainstream culture.

Carlo Caldini/Gruppo 9999

Carlo Caldini/Gruppo 9999The V&A show borrows its title Night Fever from the film. It looks back at the origins of disco culture in the 1960s and how it's developed since. This is its first show since the Covid lockdown and there's an emphasis on design - but it also looks at the clubs' social context and at the music played.

Curator Kirsty Hassard says in the 1960s Italy led the way in creating nightclubs where teenagers and 20-somethings could enjoy themselves away from the gaze of parents.

"You had clubs like the Piper Club in Rome and then more radical developments like Space Electronic in Florence which combined discotheque with theatre.

"It was the boom of youth culture. But designers were emerging into quite a limited economy so they created spaces on a small budget, which were never meant to be permanent.

Timothy Hursley/Garvey Simon Gallery

Timothy Hursley/Garvey Simon Gallery "Technology was more basic than it is today but a place like Space Electronic was pushing the boundaries of what a club venue could be."

Night Fever uses photos, artefacts (and of course music) to look at clubs such as the Palladium in New York. It was started in the mid-1980s by Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, who had already had a huge success with their New York club Studio 54 in the late 1970s.

Artists Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat each painted large murals which helped make the nightclub one of the most fashionable venues in Manhattan.

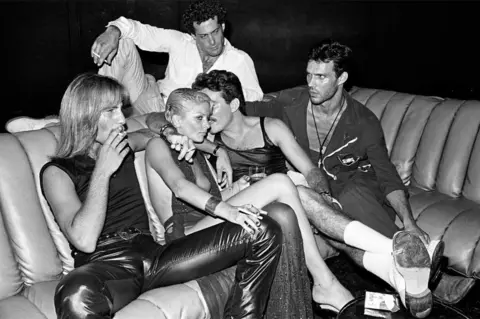

Bill Bernstein/ David Hill Gallery

Bill Bernstein/ David Hill GalleryGay culture has also had an influence on club design, especially in the US. The new show looks at gay Manhattan dance-clubs such as The Saint (which took over the space once occupied by the rock venue the Fillmore East) and Paradise Garage in SoHo, where DJ Larry Levan made his name.

Hassard says one change in the 1980s was the emergence of so-called superclubs and their function in celebrity culture.

Bill Bernstein/David Hill Gallery

Bill Bernstein/David Hill Gallery"When big venues such as Studio 54 and the Palladium were at their peak there was a lot of focus on which VIPs went where each night. Club culture became commercialised in a way it really hadn't been before and the clubs were in the newspapers all the time."

A different version of this show has been seen at the Vitra Design Museum on the Swiss-German border. Leonie Bell, director of V&A Dundee, says she's delighted to see it travel north in an expanded form.

"But we first saw it before the pandemic. I think with Covid we're really aware of the poignancy of critical cultural spaces now being closed.

Brian Sweeney

Brian Sweeney"It's part of the museum's role to be the champion of those spaces. But aside from that it's just a wonderful trot through decades of clubbing.

"There are social histories and musical histories and design histories. If you look at something like Studio 54 in New York you'll see the role of clubs in fashion and in art. There hasn't really been another exhibition like it."

Attending the show's opening was Mike Grieve, who has run Glasgow's Sub Club since 1993. The venue, opened in 1987, is one of the oldest subterranean music clubs anywhere. Its specialism is electronica and its capacity is just over 400.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Back in the mid-80s we played a mixed diet of predominantly black American dance music ranging from funk and disco and jazz to Latin and house and hip-hop. I think the first house music record that really broke through on the dance floor with us was Farley "Jackmaster" Funk's Love Can't Turn Around and it's still popular today.

"Design matters as part of a club's vibe but that's always hard to capture. For me two of the most effective clubs which had that vibe were the Haçienda in Manchester, circa 1989/1990, and more recently Trouw which was in an old print works in Amsterdam. Sadly both are now gone."

Grieve also chairs the Night Time Industries Association in Scotland. "It's great to see club design taken seriously in a show at the V&A," he says.

Bill Bernstein/David Hill Gallery

Bill Bernstein/David Hill Gallery"But there's an irony that whereas world-class museums in Scotland are finally opening up, Scottish nightlife still doesn't have an idea of when hospitality will be allowed to surface again. It worries me that some of our members may face bankruptcy."

Inevitably a lot of the appeal of the V&A's Night Fever is for now nostalgic. Leonie Bell says for her it evokes her own clubbing days.

"I was in clubs a lot in Glasgow in the 90s. The great thing was you could let go. And that means so much now with all that's been going on in the world.

"They were an opportunity to be young, to experiment, to work out who you were, to meet people who were like you or maybe completely different. But you could be free - and at the moment I think no one feels free."

Night Fever continues at V&A Dundee until 9 January next year.