Meet the songwriters who told pop stars: 'Don't steal from us'

Christopher Patey / Blythe Thomas / Griffith Park

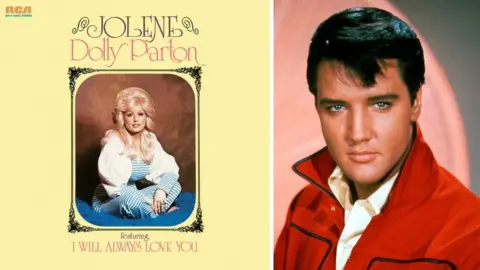

Christopher Patey / Blythe Thomas / Griffith ParkIn 1974, Dolly Parton was on a hot streak.

She had just scored two consecutive number ones on the US country chart with Jolene and I Will Always Love You, and was beginning to make inroads with the mainstream pop audience.

Then Elvis Presley called - he'd heard I Will Always Love You and wanted to record a cover.

"You cannot imagine how excited I am about this," she told him. "This is the greatest thing that's ever happened to me as a songwriter."

So why have we never heard Presley's version of the song?

Because the night before the recording session, his notoriously hard-nosed manager, Colonel Tom Parker, called Parton and told her Elvis wouldn't record the song unless she handed over half of the publishing rights.

"I said, 'Well, that throws a new light on this. Because I can't give you half the publishing. I'm gonna leave that to my family,'" the singer told Reba McEntire's podcast in 2020.

"And he said, 'Well, then we can't do it.' And I cried all night."

But Parton had the last laugh. When Whitney Houston recorded her blockbuster version of I Will Always Love You for The Bodyguard soundtrack in 1992, the country star still owned the rights, and earned "enough money to buy Graceland".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesParton wasn't the only writer to clash heads with Colonel Parker. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who wrote dozens of Elvis's hits, from Hound Dog to Jailhouse Rock, originally agreed to share a percentage of their publishing with the star - on the understanding that they'd make more money from 50% of an Elvis song than 100% of a track that didn't feature his smooth vocals.

But their patience wore thin in the 1960s when, after agreeing to write songs for an upcoming film, Colonel Parker sent them a contract that consisted of a blank page with two lines at the bottom for their signatures.

Thinking there'd been a mistake, the duo called the Colonel's office, only to be told the document was genuine. Their response? Well, it's unprintable here, but let's just say they never worked with Elvis again.

Stories like these have become part of music industry folklore. But the practices that Colonel Parker initiated still persist.

Bullying tactics

In fact, the pressure on writers to surrender their songs has become so pervasive that a group of the world's biggest hitmakers recently broke cover to bring the practice to light.

Calling themselves The Pact, they signed an open letter last month, in which they vowed to stop giving away publishing or songwriting credit to anyone who did not contribute to the music, unless they received "equivalent [or] meaningful" compensation.

You might not recognise the signatories names, but you have definitely heard their music. Collectively, their clients include people like Justin Bieber, Harry Styles, Ariana Grande, Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, Michael Bublé, Lorde and Sam Smith (although the letter was not directed at any specific artists).

Allow Instagram content?

The campaign was organised by US writer Emily Warren, after she became tired of writers being "bullied" into giving up a share of their royalties.

"That's what really pushed me to start this," she says. "I was like, 'I can't be spoken to this way by someone I'm giving songs to. It's painful and it's not right. I don't want to accept being spoken to that way.'"

Warren, who recently received a Grammy nomination for her work on Dua Lipa's Don't Start Now, says that demands for co-writing credit start with a 1% share, rising as high as 20%, with an average of about 15%.

Writers who object are told their song won't be used, or it will be relegated to an album track, harming their chances of making money.

"You've been conditioned to think that if you walk away, someone else will take your place," says Tayla Parx, another Pact member, whose credits include Ariana Grande's Thank U Next and High Hopes by Panic! At The Disco.

Allow Google YouTube content?

She says that, in recent years, artists have started demanding a share of the publishing "ninety-nine per cent of the time".

"The crazy thing is, it used to be rare. People would say, 'OK, if a legendary artist is recording the song, then maybe I'd be open to it.' But now you have even newer artists coming in and demanding it."

No bargaining power

Justin Tranter, a co-writer on hits for Selena Gomez, Britney Spears, the Jonas Brothers and Lady Gaga, says the demands frequently defy belief.

He recalls a song from the start of his career, where he and a co-writer dreamt up the chorus and the key lyric - only to be sidelined when it came to the credits.

"I was like, I wrote this lyric alone in my bedroom in a house where I live with six people, because I'm broke - and then me and this brilliant woman wrote the melody and the chorus together, and we were offered the smallest piece out of everybody.

"We fought for a tiny bit more, but we still ended up with the smallest piece - the people who wrote the most important part of the song."

Tranter says its easy for songwriters to be squeezed out because they hold very little bargaining power.

"It's a logistical thing: Without the artist, the song's never going to come out. Without the producer, the files aren't going to be handed over to the record label. So the songwriters are the only one who actually, logistically, can be dismissed. Which is hysterical, because without us, there's no song."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTranter and others stress that many major artists genuinely do contribute to the writing of songs. Even if they don't, the idea of sharing credit isn't necessarily objectionable.

"I don't care that much if an artist needs to have their name on there," says Warren, recognising that a singer can bolster their credibility if they can "go to an interview and say they wrote the song".

Instead, The Pact is calling for a "meaningful exchange" in return for a share of the publishing.

"Some people might negotiate a writing fee or an upstreaming bonus - which is where if a song reaches a certain milestone, like 10 million streams, the writer gets a bonus," explains Warren.

Another option is to give writers a share of the master, meaning they would get royalties when a song is sold or downloaded.

"There's a few different ways to cut it," says Warren. "It's up to each person to negotiate what they think."

'Wake-up call'

Since The Pact launched two weeks ago, more than 1,000 people have signed the open letter; and Parx says there has been an "incredible response" from artists and their managers.

Among them is Sam Harris, of the US rock band X Ambassadors, who called the campaign a "wake-up call".

"I've been in situations where I have asked for publishing on songs that I didn't write," he said in an Instagram video.

"And didn't at the time think, 'OK, what is this doing to these people who actually wrote the song? How are they feeling about this?' And that's not fair.

"This is a cut-throat business sometimes and if we don't look out for each other and hold each other accountable, it's just going to keep going."

Warren was impressed by his candour.

"That's such a cool and amazing response, which is what we're looking for."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPact's strategy of not naming-and-shaming artists is deliberately designed to elicit solidarity.

In any case, says Parx, singers often aren't aware that they're taking money away from their collaborators.

"Most artists don't understand the business of the music business," says Parx. "So when their manager or their label tells them, 'This is what you're going to do', that's what they do.

"And I don't even hold it against [managers] when they try to get the best deal. They're doing their job. But you have to also understand there's the right way to do that, and there's a middle ground to be found."

'Baby steps of self-respect'

Certainly, that's a more palatable approach than going to court. Recent years have seen writers and performers racking up millions of dollars in legal fees as they fight to prove ownership of a song.

The two highest-profile cases concerned Led Zeppelin's Stairway To Heaven (the estate of Spirit guitarist Randy California unsuccessfully claimed the band had stolen the riff from him) and Katy Perry's Dark Horse (the case, which is still ongoing, centres around a four-note motif that appeared in an earlier song by the rapper Flame).

Lauryn Hill was also accused of stealing songs for her Grammy-winning solo album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. That case was settled out of court for a reported $5m (£3.6m). Meanwhile, a trial involving Ed Sheeran is set to take place in the US over alleged similarities between his song Thinking Out Loud and Marvin Gaye's Let's Get It On.

Cases like these illustrate how hard it is to establish who wrote what in the studio - and the writers behind The Pact acknowledge that negotiating such deals can be a murky business.

Their goal, therefore, is to unite against bad practices and force the music industry to recognise the value of its songwriters.

"For us to have been put in a place where I'm so unimportant that I'm not even going to fight back when someone's stealing from me, is so twisted," says Warren.

"This is the first baby step of self-respect."

Getty Images

Getty Images"This isn't just songwriters against everybody," adds Parx. "It's everybody against the old way of doing business. And that benefits everybody at the end of the day."

That said, Warren isn't afraid to get tough if the industry refuses to play ball.

"If this goes on, we'll probably give one warning and then we're not going to be afraid to post correspondences and stuff like that," she warns.

"But luckily, I've found that [we're making] a pretty bullet-proof point. It's hard to argue the other side and not sound like you're stealing - so that's been pretty cool."

Tranter stresses that the campaign isn't about making more money for himself.

"My life is great," he acknowledges. "With lots of luck and a shocking amount of hard work, I got through the exploitation and still found ways to have a life that I dreamed of.

"So this is not about me at all. I want to make sure that the next generation of songwriters, who have maybe only had one hit, or a couple of album cuts, can pay their rent."

If it works, says Warren, it could fundamentally change the way music is made.

"Right now, when you get songwriters in the room, they're trying to write a radio hit, because that's the only way you make money.

"If we create an environment where songwriters are not worried about this, if they're not freaking out about paying their rent, and they're just able to focus on being creative, there will be a musical renaissance.

"It will change everything."

Follow us on Facebook, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.