How Covid is ‘creating a new genre’ for live music

Anglo Management/Hot Since 82

Anglo Management/Hot Since 82As an international touring DJ with an album to release, Hot Since 82's hectic schedule for 2020 didn't originally include playing from a hot air balloon.

Nor beneath the pier of a deserted Hartlepool beach - to a live audience of seagulls.

But then he didn't originally plan on Covid unexpectedly unplugging nightlife as we knew it.

By emptying stages and dancefloors, the pandemic has generated an urgent need to reimagine the live music experience - both for artists and the audience stuck at home.

So, how is Covid reshaping the creative thinking behind live music performances, and what lasting impact could there be?

Hot Since 82's manager James Drummond says "lockdown forced people to think differently".

"Our mindset's always been that way, so we saw it as a challenge," he says. "We thought, well if everyone's at home and can't go to a venue - what's the best experience we can give them? The natural environment was our answer."

The pier and balloon sets - filled with vast landscapes and stunning drone shots, recognised the restrictions of the world, but also offered "a different kind of adventure" for music lovers, Drummond says.

Allow Google YouTube content?

'Cinematic experience'

The sense of opportunity is shared by Alex Lill, the creative force behind The Weeknd's recent videos and live performances.

"Before the pandemic even hit we were trying to reimagine how we could provide a cinematic experience for the audience at home, not just the live audience," he tells the BBC.

Last January's immersive performance of Heartless on the US's Late Show with Stephen Colbert demonstrated this.

Rather than rely on the traditional stage and live audience set-up, it followed The Weeknd backstage in single-shot as he performed through a surreal dream-like sequence, which ended with him arriving at the 'live' studio stage to greet the in-person audience.

Allow Google YouTube content?

"When Covid started and live audiences were out the window, only then were we given more licence by various television networks and platforms to pursue this new approach" says Lill.

As audiences moved online, that new way of thinking - once seen as a curious experiment by execs - became a firm necessity.

A summer livestream concert by Dua Lipa raised the bar for Covid-era production values, with a large and highly choreographed cast of dancers, guest singers and musicians performing in an old warehouse.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFast-forward to The Weeknd's medley performance of Save Your Tears/In Your Eyes at last November's American Music Awards, and the evolution is clear.

Made in the midst of the pandemic, Lill took the single-shot tracking style and moved it outside onto the bare streets of Los Angeles, transforming the real-world Covid backdrop into his stage. Complete with fireworks, timed pyrotechnics and high-angle shots, it made the location and its atmosphere an active part of the performance.

The sense of innovation and The Weeknd's trademark use of face bandages - part of an anti-drink driving campaign and a comment on Hollywood - culminated with his Super Bowl half-time show on Sunday.

'Entirely new genre'

Working within the limitations of the pandemic is a challenge that Oscar Sansom, creative director of Forest of Black studios, describes as the "colliding of two worlds".

"The new world of filmed live performance since Covid is creatively very exciting as it is an almost entirely new genre," he says.

For Sansom, the challenge is now about how to convey some of the "energy and emotion" of traditional live music by filming in new ways and locations.

Allow Google YouTube content?

Take his work shooting Liam Gallagher aboard a barge as it floated down the River Thames last year. Filmed with London's lockdown skyline and landmarks in full view, it gave the rendition of his single All You're Dreaming Of an added poignancy after a year of loss.

"The show explored that, without an audience, the nature of a live show can evolve into something totally different," says Sansom. "It's now so open, the circumstances invite an exciting sense of possibility."

Energy and intensity

This freedom has meant some live performances go in the other direction, using intimacy to both reflect and reject the pandemic and social distancing.

To close Biffy Clyro's pandemic gig, livestreamed without fans from Glasgow's famous Barrowland Ballroom in September, Sansom built a cube for the Scottish rock band to play inside.

Allow Google YouTube content?

"I saw it as a metaphor for the separation we were all feeling and that the band felt from their fans," he explains.

"Inside the cube the band could see nothing but their own reflection, whilst the 'in person' audience [the camera operators] were kept at a distance by the glass.

"It felt reminiscent of the screens we have all become used to communicating through recently. It also created this moment in the show for where they were completely separated from everything and everyone else on the set. It was just them playing without any cameras or crew to distract them. It created this bubble of normality for a song."

That in turn had a direct impact on the tone of the performance, which became a release of pure frustration, says Sansom.

Getty Images

Getty Images"With the camera so close, when Simon Neil [lead singer] screams those final lyrics with such energy and intensity that it gives me goosebumps every time I watch it," he says.

"We capture the incredible raw energy of their live performances in a way that had never been seen before."

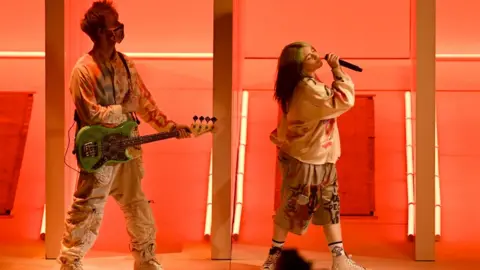

For her AMA performance of Therefore I Am, Billie Eilish worked on creating the illusion of increased space within the pandemic distancing constraints.

Inviting the viewer to follow Eilish through a seemingly endless maze of corridors, it aimed to replicate the track's video, which tracked Eilish as she explored a deserted shopping mall.

Allow Google YouTube content?

"On the surface this looks like a simple solution for the performance but actually what it does is provide a playground of corridors in a confined stage setting," says Hollie Wright, lecturer in design for performance and stage management at Birmingham City University.

"The cinematography plays with the idea of space to begin with, and provides an intimate setting for the audience. What's interesting is that it waits until the end to reveal all elements of the set in one shot.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA lasting impact?

Many performance spaces have evolved to meet as audiences have moved online.

London's Barbican is one such example. When the pandemic hit, its head of music, Huw Humphreys, worked to bring their scheduled Live from the Barbican programme online.

Additional cameras were installed around the concert hall and stage to provide viewers with an experience that was familiar but fresh.

Mark Allan

Mark Allan"The audience are treated to a real variety of shots and all sorts of angles that people wouldn't have seen at one of our concerts pre-pandemic" he says. "It's put a lot of our future plans into hyperspeed, but a challenge we've relished."

The advantages of moulding the traditional live experience for an online audience have already started to become clear.

"In the future we want to have a full concert hall and an audience watching remotely as well, because this allows us to reach people internationally," says Humphreys.

Mark Allan/Barbican

Mark Allan/BarbicanLooking ahead to the creative legacy of the pandemic on live music performance, Sansom is similarly optimistic.

"Dark times often seem to propagate some of the most exciting creative works," he says. "I have no doubt that the current global situation will have a profound and lasting impact on both the music and creative industries, but I believe that creative people, by their nature, are adaptive.

"I think the silver lining for me is seeing what incredible and inventive creations will arise from this unfortunate situation we all find ourselves in.

"I feel like we are at the start of something very exciting with virtual shows and that the creative journey will go beyond this pandemic."

Follow us on Facebook, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected].