What changes will 2021 bring for the media world?

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryWell, my media predictions for 2020 were a load of rubbish, weren't they? I didn't see a pandemic coming. Then again, neither did you, unless you did; in which case, you must be very rich, and I'm free for lunch when restrictions have eased if you fancy it?

I suppose I could blame Covid-19 for the failure of ITV to be bought, as I said it would, or the lack of a re-balancing between trends and events in news. But the truth is that - alas! - they were dud predictions.

Why on earth you'd be interested in the contents of my crystal ball for 2021, then, I really don't know. And yet the ball is full. And wanting to be written about. So here goes, and remember, all forecasters are frauds. Even the ones who acknowledge that fact.

1/ The year of Digital Trustbusters

The end of 2020 saw a flurry of moves by governments around the world to regulate the data giants more effectively, particularly in the economic sphere where they tend toward monopolies.

India's regulators said they'd look into whether the relationship between Google Pay and its Play Store for Android apps was too anti-competitive. In China, the authorities are going after Jack Ma, the country's richest man, in a remarkable regulatory gambit that could lead to the break-up of his company. And the EU has accused Amazon of using the data it has on customers to rig the market in favour of their own-label products.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryIn the UK, the Online Harms Bill was finally announced in parliament, though it's a tangled affair and focuses mostly on social rather than economic harms.

In the economic arena, the Digital Markets Unit, part of the Competition and Markets Authority, will make its first, landmark rulings.

In America, the Department of Justice is suing Google for allegedly violating anti-trust laws. And Facebook has been hit with lawsuits from both the Federal Trade Commission and the attorneys general of dozens of states.

For 15 years, the data giants have had a relatively free ride from regulators; in recent years, they have spent so much on lobbying that the status quo has mostly continued, despite the astonishing growth in their power, and mounting evidence of some social and economic harms, amid countless benefits.

The above actions amount to such a flurry of activity - in which various politicians are vying to be the ones who bring Big Tech to heel, and all countries are looking closely at others to see what they can learn in this new policy arena - that 2021 feels like the year in which a new settlement between technology and democracy arrives, especially in the West.

By the way, had Joe Biden chosen Elizabeth Warren, who wanted to break up these companies, as his treasury secretary, things could have been even worse for the digital kings of California. Instead he chose Janet Yellen, a labour market specialist. Biden's administration has immediate priorities other than breaking up complex companies, of course.

Interestingly, while Sir Nick Clegg was hired by Mark Zuckerberg to explain Europe to Facebook and Facebook to Europe, his relationship with Biden - they were deputy leaders of their countries at the same time - could prove more useful or important to the company than his knowledge of Brussels.

2/ China fights hard in the Tech Cold War

All this will happen against a backdrop of the internet itself splitting into different domains, something I've done a lot on this year. China's digital infrastructure will try, through the likes of Huawei and TikTok, to grab the attention and affection of people on the other side of the world to Beijing. The battle is on to shape the internet for the nearly 3 billion people not yet online.

Biden's administration sees technology as a geopolitical issue, so expect ever more rows over whether Chinese companies should be allowed to operate in the US, which will spill over into the UK and Europe.

3/ Gaming charges on

Gaming was one of the fastest growth sectors in media and entertainment even before the pandemic. Then, with tens of millions locked indoors with broadband as their only salvation, interest and demand exploded.

This dizzying growth in gaming, which investors are very excited about, is driven by dramatic improvement in the quality of digital distribution, as much as the creativity of the designers. Super-fast broadband has allowed multi-player international formats to become an exhilarating live experience online, powering eSports and making a lot of young people in particular really quite rich.

Just as the likes of Apple and Amazon have moved into the content business when it comes to TV, I expect them to radically accelerate their investment in gaming. (Amazon already owns Twitch, of course). Gaming will occupy a growing share of the content business of the future. Naturally, the data giants want to dominate that business. I predict Apple to make Arcade, its gaming offer, much more central to its growth. Might one of other content kings, like Disney or Netflix, also bid for one of Britain's gaming success stories, like Rebellion Media, which I visited in 2020?

4/ Cinemas will decline, mostly into franchise and immersion specialists

You may not spend a lot of time thinking about Warner Bros or HBO Max, an American media giant and its streaming service respectively. But when Warner announced a few weeks ago that it was going to release its 2021 slate of films simultaneously on HBO Max and at cinemas, it amounted to a huge moment in the history of film.

Driven by Netflix and other streaming superpowers, top quality movies are heading homeward. In recent years, cinemas haven't so much been in decline, as forced to focus on franchises like Marvel. These shows benefit more from giant screens and surround sound, which are expensive and inconveniently large at home, than gritty independent films.

Press Association

Press AssociationMega franchises are sometimes called 'bankable blockbusters'. because they always deliver big ticket sales, and their super-hero story lines can be translated into lots of languages, not least Mandarin, Urdu and Spanish, which between them offer access to well over a billion people.

So cinemas, unless they're in that tiny minority that celebrate small independent films to a very committed film buff audience, will have to further adapt, offering immersive experiences in which other aspects of your visit transport you to another world. This adds cost, of course.

And cinemas are already at the mercy of lockdowns. Despite optimism about a vaccine, many local picture houses have been shut for months. But doubling down on what cinemas do uniquely is the only option when I can get iPlayer, Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney Plus at home.

5/ The inevitable Grand Re-bundling

…Talking of which, I can also get Spotify, and Audible, and Britbox and... all the rest. We live in the attention economy, and the battle for our ears and eyes is intensifying by the minute.

As night follows day, the laws of economics re-assert themselves. Consumers have finite disposable income, and for many it has fallen over the past year or will fall, given we are embarking on the worst recession for centuries.

It follows that we cannot just keep on paying for lots of different subscriptions. At some point - surely - we have to rationalise. And media giants will want to ensure their services are not the ones being ditched. Two strong ways of doing this are to reduce the price, though that reduces profit margins; or - which may have greater economies of scale - throw extras in (though that obviously trims margins, too).

Amazon Prime is a bundle. Sign up for free or cheap delivery on goods and get yourself some Premier League action and TV programmes for no added costs. Disney are now bundling aggressively, throwing theme park passes and merchandise in with its streaming platform, Disney Plus. Apple One offers ad-free search alongside the latest Mac.

In an age of over-supply of content, consolidation is inevitable. The Grand Re-bundling of content, sometimes with experiences thrown in, is a form of consolidation. It has already begun. We will see more of it in 2021.

6/ New prototype glasses point to an augmented future

A well-placed birdie in Silicon Valley told me that, over the coming year, some of the big tech giants will invest even more astronomical sums in augmented reality (AR) than they already have.

At the start of 2020, Mark Zuckerberg did a media blitz after this post, in which he said that while the mobile phone was the decisive technology platform of the 2010s, augmented reality glasses will be decisive in the 2020s.

If 2020 was the year of Zoom, I expect AR glasses to be going mainstream by 2025. Who knows, by then you might even be using one while tucking into your turkey.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryThe idea is to wear glasses that allow you to add digital elements to the real world. Facebook is already investing massively in this arena. I predict this company alone will invest over £10bn in augmented reality in 2021.

Over the coming year, amid all the new Tesla models, smartphones, and wearable watches, expect a few demonstrations of glasses that learn the lessons from Google Glass. Just because that project was a flop, doesn't mean others will be.

7/ Might the Substack revolution power a local renaissance?

Some people, including me, have described it as a "revolution", but what Substack has done is rather, um, er, old-fashioned. It's as if someone in journalism said, "I know! I've got a great idea! Why don't we ask customers to PAY for our stuff?! That way we can feed our families, and keep making the stuff! Everyone's a winner! Viva capitalism!"

In case you have no idea what I'm talking about, Substack is a user-friendly platform that allows media content creators - Oh Stop It Amol! They're called JOURNALISTS for goodness sake! - sorry, journalists, to build their own media empires, chiefly through newsletters. It includes the radical idea of... charging customers. Substack keep 10 per cent.

Star journalists like Andrew Sullivan, Matt Yglesias and Glenn Greenwald in the US are now on Substack. In the UK, Ian Leslie's The Ruffian and Helen Lewis's The Bluestocking are among those with a growing band of followers and so too is James Crabtree's newsletter, Thoughtful. Crabtree is British but based in Singapore. Many of the above don't charge, yet. The idea is to build an audience first, then monetise later. Like I said, radical!

What is most intriguing about all this is that the Substack model of paid-for newsletters might - just might - be able to rescue the broken news model of local news in the UK. It's already happening. Look, for instance, at Manchester Mill, set up by Joshi Hermann: it's built a decent audience quickly.

People will pay for stuff if they want it enough. Local journalism is something people do want. Many of the bigger groups are pivoting to charging for their content online. Might the simplicity of the Substack newsletter model offers one path to salvation for a vital part of our democracy? I predict dozens of new local Substack titles, like Manchester Mill; one or two flagship newspapers moving completely to this new, digital distribution; and many more local titles charging for content.

8/ A new BBC chairman - and potential funding model

The BBC will get a new chairman this spring, to replace Sir David Clementi. There is plenty of chatter about the possibility of it being Richard Sharp, a former Goldman Sachs banker. He is clever, very wealthy, seen by No 10 as politically sound, has a strong track record in the arts, and is close to Rishi Sunak. Sharp described the chancellor to a friend as the best young financial analyst he'd seen.

Of course, the job may go to someone else, but as things stand it looks like going to a relatively conventional applicant, rather than a renowned critic of the BBC such as Charles Moore, who has ruled himself out.

One of the first tasks for this new chairman is to help Tim Davie, the director-general, come up with a funding model for the future of the BBC. In 2021, the detail of a new model will emerge. The licence fee will remain core, but as part of a mixed package in which subscriptions are offered internationally.

In No 10, Davie is respected and thought to have made a strong start. But, with a new chairman by his side, it's in the spring that the intellectual and political heavy-lifting of his reign will really begin.

Expect to see: a subtle shift in the focus of BBC diversity targets toward socio-economic background, while still going for his 50% female, 20% BAME, 12% disabled target; a radical emphasis on non-metropolitan audiences; slick new branding and marketing for some integral parts of the BBC operation; and a public offensive to make the case for the BBC as central to the growth sector that is the UK creative industries.

9/ GB News will make no profit but a big impact

Television news is very expensive. GB News, the proposed new free-to-air TV service funded by advertising, and backed by US giant Discovery, is unlikely to make a profit for many years. But, after a launch delayed by several months because of the pandemic - and so long as its backers don't get too nervous - I expect it to have a big effect.

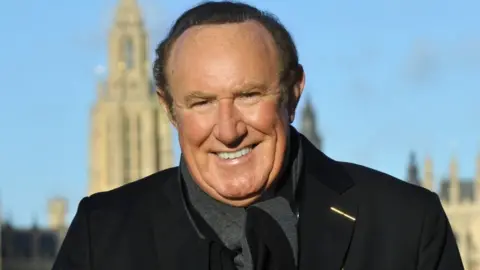

And for two simple reasons above all: first, demand; second, Andrew Neil. On the first, demand for news and opinionated chat has soared in the past year; and of course through social media GB News can reach a big international market through clips. This will generate marketing and promotion rather than paying subscribers, of course.

On the second, Neil is a formidable business and media figure, and will work every waking hour to ensure this last big chapter in his storied career is not a flop. He sees himself as breaking the mould for the third time in his career (after his editorship of The Sunday Times, and his chairmanship of Sky).

As long as the backers don't pull out, GB News will make some big-name signings; inject a lot of cash into the bloodstream of British media; generate a chattier, more opinionated kind of news programming while stopping well short of Fox News deceit and conspiracy; and create countless viral moments. This, being an antidote to the stentorian BBC, will count as success aplenty for the backers, who know it will be many years before they see a financial return.

10/ PSBs will offer much more on-demand exclusivity

Spitting Image has been a hit for Britbox. It offers a model to the other public service broadcasters, who can use exclusive content to boost their digital offerings.

ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5 have to ride two horses at once: conventional linear TV, which is ad-funded and suffering from structural decline against the streaming giants; and their own streaming platforms, which they need to build up as quickly as possible.

I often wonder if many consumers actually realise how much free content there is on these platforms. For instance, All4, the on-demand service from the UK's Channel 4, has thousands of hours of world-class programmes that you can watch for... free. This is remarkable. Sure, there are adverts. But if your idea of a good time is repeats of, say, Brass Eye, you can have your fill.

At present, All4, 5OD and ITV Hub represent a small fraction of the revenues of Channel 4, Channel 5 and ITV. That needs to grow. In 2021, I suspect these platforms will start offering more exclusive content, perhaps yet more spin-offs from successful formats like I'm A Celebrity... or Gogglebox.

11/ Channel 5 will grow its share of weekday primetime viewing

By targeting older viewers - who after all are more likely to watch linear TV - with feel-good, heartland narratives, often featuring presenters that were integral to the lives of older viewers for many years - Michael Buerk, Chris Tarrant, Michael Palin, Jane McDonald - and avoiding COVID-19 while others doubled down on it, Channel 5 has had another stellar year.

Channel 5 often beats Channel 4 (and indeed BBC Two) on weekday evenings already - though not when blockbusters like Bake Off or Gogglebox are on.

Ben Frow, the Channel 5 boss, was very open about his strategy in this long interview I did with him for The Media Show. The editorial improvement in Channel 5 has been a boon for British television. By the end of next year, when the backlog from productions stalled by the pandemic has begun to clear, I expect Channel 5 to beat Channel 4 three weekdays out of five.

12/ The Guardian won't charge, make a compulsory redundancy - or a profit

Well you need one dead cert in a batch of predictions, don't you?

Under current editor Kath Viner, The Guardian pulled off a remarkable turnaround in three years, finally achieving profit. Then the pandemic struck, and undid years of work in just a few weeks.

The trouble is, the earlier turnaround involved a huge amount of pain: that is, job losses. At some point though, you run out of jobs to cut. And the Guardian has a proud tradition of never having made a compulsory redundancy. This obviously has moral value, but close to a dozen journalists there, including some very senior ones, have said to me in recent years that it means you just can't create a modern digital newsroom with your best people in the right positions.

The senior team have looked at the idea of a paywall, and don't rule it out. There is growing evidence that people will pay for content beyond a monthly fee for mobile or tablet apps. See the New York Times, Telegraph, Financial Times and Substack. Moreover, a once-in-a-century pandemic might be a good moment to say to readers: "Sorry, but we just have to [charge]. You used to pay for the paper. Now would you please play for the website?". This would be a historic move. Viner has the authority to do it.

Sadly, in the short term, like so many other publications, I predict The Guardian won't be profitable in 2021. The fact that this is not a brave prediction is indicative, I think.

For anyone interested in a Review of 2020 in the Media, here's a 26-min TV programme I made with my producer colleague Elizabeth Needham-Bennett, much of it shot by the outstandingly talented cameraman Rob Taylor.

I wish all readers of this blog a very happy and healthy New Year.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter or Facebook; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from Radio 4.