The Russell Prize 2019: A celebration of the year's greatest prose

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd so we come again to that glorious moment in the calendar when the Russell Prize is given to a worthy recipient.

You know the gist by now, having no doubt witnessed the prize-giving ceremony with open-jaw awe this time last year and the year before.

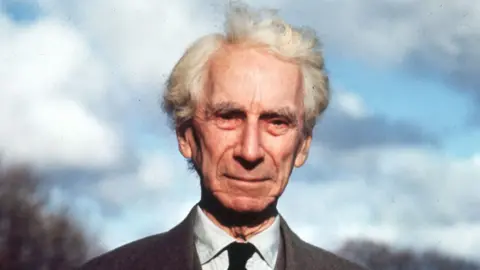

In case, by a terrible misfortune, you missed one of those occasions, let me remind you that these awards are named for my hero Bertrand Russell, who wrote the greatest prose of anyone typing in English in the 20th Century, by uniting three qualities in unique glory: plain language, pertinent erudition, and moral force. Very, very few writers have ever come close to achieving all three; none have approached Russell's eminence.

Let me also remind you that the selection process was typically thorough, in that nominations were submitted by me, to a rigorous and impartial panel of one, also me, wherein I have self-identified (quite rightly) as convenor, founder, chair and president.

This year's winning entries have a twist. You'll have to wait until the end to get there.

In a break from previous years, for which there is no particular justification, this year's winners are ranked in reverse order.

5/ Dominic Cummings: The Machiavel in Downing Street, by Harry Lambert for The New Statesman

The long-form profile can be a glorious thing. Lauren Collins and Ian Parker mastered the art in recent years for The New Yorker, often by securing access to a subject and spending lots of time with them, in order to alight on the most telling details. It is harder when you don't have access.

In this cover story for the New Statesman, for whom I was briefly a columnist last year, Harry Lambert managed to significantly enhance our understanding of one of the most powerful and caricatured, but least understood men in Britain. It contained proper, deep reportage, including an illuminating phone call to Cummings' parents, a meeting with his uncle, and a conversation with his old head-teacher.

It was written in plain prose, but contained urgency and moral invective. To the best of my knowledge, Russell didn't write profiles of contemporary political figures, preferring philosophers both ancient and modern. But he would have found this excellent profile enlightening, which after all is one of the main aims of philosophy.

4/ The Jungle Prince of Delhi, by Ellen Barry for The New York Times

While we're bending the rules of this prize to accommodate reportage, the most enjoyable reporting I read this year was a riveting, astonishing long read by Ellen Barry.

New York Times

New York TimesI actually don't want to give too much away, because if you haven't had the pleasure, well, you should, perhaps on Christmas day when the sherry is going down.

She relates the tale of a mysterious family who, ripped asunder from their ancestral home by Partition, find themselves abandoned, and then defiantly staying put, on a railway station in India, before laying claim to a beautiful, part-ruined palace compound deep within a pocket of jungle that bisects old Delhi. It's all about the Royal House of Oudh, you see; except it's not altogether clear the Royal House of Oudh exists, and it turns out the truth about it is in the head of a family relation in northern England.

Over many years, Barry meets them all, and finds the truth. I hope she's got the film rights. I'm telling you, it's nuts.

3/ Jeff Bezos's Master Plan, by Franklin Foer for The Atlantic

Readers of my blog will know that I am mildly obsessed by the fact that data is now the most powerful commodity on earth, consumers know far too little about how their data is used, and policies that transfer ownership and control of data from vast corporations to individual citizens are interesting and possibly inevitable.

Leonardo Cendamo/Getty

Leonardo Cendamo/GettyOver the past couple of years, Facebook and Google have been cast as the main bad guys of Big Tech. That was always a bit myopic. This year, it feels like the heat is turning up on Jeff Bezos. Not just because he's the richest man in the world, but because of the all-consuming nature of his company's ambition, its record on tax, and the industries it is affecting - with all the impact that has on cherished ways of life.

Franklin Foer understands these issues better than most. His cover story for The Atlantic gets to the heart of Bezos's thinking, but does so with deep erudition relating to modern technology, plain language, and shameless moral invective. If you want to understand what drives Bezos, this is the article you need to read.

2/ The Class Ceiling: Why it Pays to be Privileged, by Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison (extracted for The Guardian's Long Read)

Ok, ok, I'm biased. And this was an extract rather than an essay. But tough. The writing justifies the further bending of the rules, and I'm in charge here. Dr Friedman featured in a documentary I did for BBC Two, called How to Break Into the Elite. I provided a quote for the paperback edition.

He and Laurison brutally, and methodically, show the existence in Britain of a class pay gap. They show the subtle but often sinister effects of privilege and prejudice, and how they operate in the workplaces of Britain.

This should be read and understood by anyone who claims to be interested in diversity or class. The book from which this essay is taken is at times much more academic in its approach than Russell was in his.

But the essay I'm referring you to above has the trinity of virtues Russell's writing displayed at its very best.

1/ The Hidden Art of Bing Crosby, by Clive James

"Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric". This wisdom from Bertrand, who often treated rules as if they were only there to be broken, is part of my justification for bending the rules yet further, in declaring this year's winner of the Russell Prize to be an essay written many years ago.

It's kind of irrelevant when it was written, really. It's just my favourite from one of the great prose masters of my lifetime, Clive James, who died a few weeks ago.

Reuters

ReutersSo many brilliant tributes have been written to him, not least by Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker, that I won't add too much here, except to say he was a great inspiration to all of us who care about what Russell cared about. This very frank, and very nostalgic radio programme with John Wilson gives a particularly affecting insight into his character.

In choosing which of James's essays to highlight for you, I wanted to do two things: first, avoid all the usual references (Schwarzenegger looked like a brown condom full of walnuts, etc); and second, adhere to the qualities of Russell's prose.

In this wonderful, elegiac, supremely wise essay on the vocal styles of the great crooners, James identifies precisely what it is that makes a singer's voice resonate. His prose is the model of perspicacity and economy. Never a wasted syllable; always the deepest insight. Look at these two analyses:

"But the great role model of my first bathroom period was Frank Sinatra. He, too, sang from the standard repertoire, but by selection and presentation he dragged it towards the forbidden"

And…

"Uniquely among the crooners, Dean Martin adapted the suppression of terminal consonants to his singing style. In London at the moment, an Italian restaurant called Da Paolo in Charlotte Place plays Dean Martin tracks one after the other as background music to the evening meal. For those of us who grew up marvelling at Dino's ability to exhale a satiated moan along with the fumes of the third cocktail, here is vivid evidence that our memories are exact: he really did keep missing out on the final 's' as if the olive had got into his mouth along with the gin, and he really did bring English into line with Japanese by eliminating the difference between the singular and the plural."

Later, James returns to Sinatra. Again, look at how penetrating the insight is - the depth of understanding conveyed in the fewest words possible.

"Every inflection Sinatra sang came from the spoken language. By no paradox, he did the same for screen dialogue. His sense of the music inherent in speech - not the music that can be imposed on it, but the music already in it - made him a revolutionary screen actor. Alas, he was too impatient to become the screen giant he might have been."

These sentences themselves resonate with greatness, from the pen of a great man. They are from a collection of essays called The Meaning of Recognition. To me, the meaning of recognition is giving this prosaic and poetic hero his due, by linking him to a mind and pen that he would have admired. James and Russell had very different politics and beginnings, but in their writing they showed the rest of us what words are capable of.

And finally… word just in from the judges is that they want readers to get a bonus recommendation for the holiday season.

I'm delighted to do as they wish. So here goes.

It is clear to anyone who bothers to pay attention to the subject that in complex but awful ways, social media is destroying our public domain. This is a psychological as well as technological phenomenon, and you won't read a better explainer of how social media has gone wrong, than this masterpiece by the great Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell.

The Dark Psychology of Social Networks, for The Atlantic

May plain prose and erudition long outlast the injustices our esteemed winners have sought to vanquish.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter or Facebook; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from Radio 4.