Coldplay and Selena Gomez: How two music releases reflect a changing industry

Getty Images/ BBC

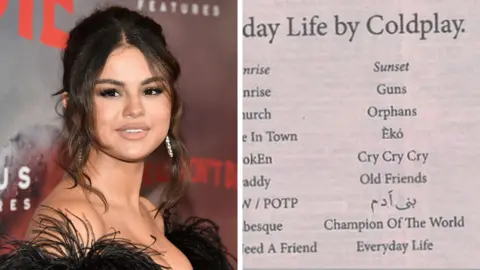

Getty Images/ BBCIt's been a big day for fans of Selena Gomez and Coldplay.

The former Disney star announced a surprise single in a post to her 158 million Instagram followers, while - in contrast - the British group chose to reveal the tracks of their latest album in a local newspaper.

Coldplay's retro marketing move harks back to a time before artists made announcements on Instagram.

So how has the internet changed the way music is released, and is it really that different?

Cutting out the middle man

Gomez is not alone in announcing new music directly to her followers.

Ariana Grande shocked followers by releasing her album's title song without any prior warning last November, while Taylor Swift has announced everything from album titles to release dates on Instagram.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe tactic cuts out the "middle man" of traditional media - whether that is radio, television or print - says Nick Reilly, a journalist at NME.

"Selena Gomez knows when she puts that single up there that there's going to be an instant reaction, you're talking thousands of streams within minutes," he says.

"You don't get more direct than saying it right to your fans who are following you."

Cryptic clues

That is not to say that there is not a carefully crafted marketing strategy in how artists communicate with their followers.

In August, British group Little Mix posted a 15-second teaser of their next song on Instagram. This month, former One Direction singer Harry Styles broke a lengthy Twitter silence when he tweeted the word "do" - a hint at the title of his second album.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor Reilly, it is an effective strategy for artists because followers "track their every single movement and read into it".

"Drop the smallest hint of something relevant and the fans will immediately latch onto that and do deep dives into music on the horizon," he says.

"These kind of fandoms are following their every move."

'Part of the fandom'

Penny Andrews, a writer and researcher specialising in internet cultures, says fandoms - or subcultures of fans - foster a strong sense of community and identity among their members.

"Fan bases have always existed; you're an act and you have fans, but they're not necessarily in touch with each other," they say.

"Now everyone considers themselves to be part of a fandom specifically, it's a personal choice. It's not like: 'I really like Ariana Grande'. You are part of the fandom. You will comment first whenever she posts an Instagram, you will be in contact with other fans, you will create content around that.

"I suppose it's why you'd want to be a football fan as opposed to somebody who just goes and watches football."

Members of a fandom often group together to boost their artist's position in the charts after a song's release, just as "street teamers" did in the 1990s and 2000s, Andrews adds.

"You would have a 'street team' - you'd recruit of fans who would try to get other fans, and themselves, to ring up the local radio stations [and] try to make it look like there was organic demand [for the song]".

Today, fandoms coordinate streaming a single or music video in order to boost the track immediately after its release.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRush releases

The UK singles charts began including plays on streaming services in 2014 and music video streams and downloads last year.

The rise of streaming has also encouraged artists like Selena Gomez to release music without warning, says music journalist Joe Muggs, because platforms like Spotify have blurred the lines between promotion and consumption of tracks.

Before streaming, he says, the difference was much starker.

"There would typically be a much longer lead up to new music being released, with tracks played on radio [for] a long time before the public could buy the record," he says.

Today, artists and record labels want fans to be able to press play from the get go.

"They don't want people to listen to 'rips' of radio plays, which they can't easily monetise and monitor as they can with normal streaming plays," he adds.

Instagram killed the radio star?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, radio still matters, Muggs admits, particularly when BBC Radio 1 DJs who specialise in a particular genre premier new artists.

Even for more seasoned artists, such as Coldplay, it remains a way to publicise their music.

Radio 1 DJ Annie Mac will play the world exclusive of two tracks from the band's new album, Everyday Life, on Thursday evening.

From albums to singles

There has also been a seismic shift from the prioritisation of albums to the frequent release of singles.

In the pre-internet era, there was often not long between the release of a single and the entire album.

Wannabe, the Spice Girls' first single, was released less than three months before their debut album, Spice, in 1996. A decade later, Amy Winehouse's hit Rehab came out as a single four days before Back to Black, her second album.

Fast forward to 2019, and Dermot Kennedy has only just released his debut studio album, despite releasing his first single four years ago.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIs it always New Music Friday?

Chart followers will also have noticed a shift to "New Music Fridays" over the past few years.

In the past, different countries released new music on different days of the week. In the UK, that was Mondays.

However, in 2015 the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) announced that Friday would become the "global record release day".

Explaining the change at the time, Edgar Berger of Sony Music Entertainment said: "Hits can come from anywhere and spread everywhere.... now all artists will be able to reach their global fan bases on the same day."

But Selena Gomez and Coldplay debuting their new songs for the first time on a Thursday shows that it doesn't always go to plan. They might just be one step ahead of the game this week.

Follow us on Facebook, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected].