Will Gompertz reviews Van Gogh and Britain at Tate Britain in London ★★★★☆

BBC

BBCThere's no point beating about the bush: if you possibly can, go and see this show at Tate Britain.

The time and ticket expense (a chunky £22 standard price) will be worth it simply to stand in front of Shoes (1886) for a few minutes.

It is Van Gogh in top form.

Two battered black boots, laces asunder and soles heavy with mud, are left forlornly in the middle of the canvas with no evidence of their exhausted owner. They remind me of late Rembrandt, Vincent's fellow countryman and guiding star, who had the same knack for showing the effects of hard labour with unsentimental honesty.

These are the shoes that inspired Beckett's Waiting for Godot and, as you will see in the exhibition, William Nicholson's Miss Jekyll's Gardening Boots (1920).

Take your chance to look at Van Gogh's depiction of crusty weariness while you can.

Van Gogh Museum; Tate Britain

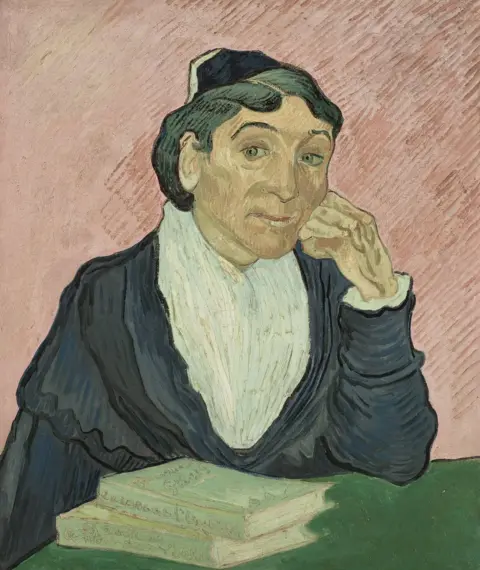

Van Gogh Museum; Tate BritainIt is a masterpiece of his canon, as are two other works in the show, painted when poorly in Provence in 1889: Augustine Roulin (Rocking a Cradle), and Hospital at Saint-Rémy.

Oh, and there's Starry Night (1888) and Sunflowers (1888), too.

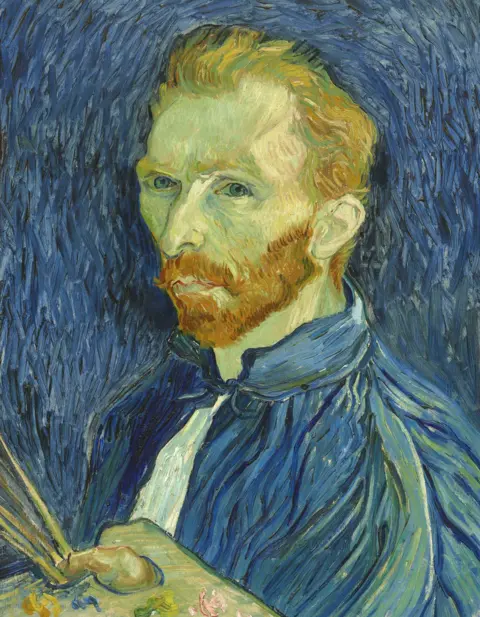

All are stunning pictures, each revealing a slightly different style and approach by the 30-something artist who had more fire in his belly than a power station's furnace.

To be in the same space as these paintings is like being hard-wired into the earth's energy supply: you can feel the life force.

He didn't merely paint what he saw. He painted what he felt about what he saw. And he felt a lot.

Hence the expressive lines, the thick impasto oils, and vibrant colours. Van Gogh didn't so much as wear his heart on his sleeve, he wore it on the end of a fully loaded paintbrush.

The National Gallery

The National Gallery

He was a restless artist in every way; constantly experimenting, obsessively working, and frequently relocating (often after the demise of an intense relationship). He was a peripatetic painter, settling at first in the Netherlands, then Paris, and finally, during his last months, in the South of France. He was, as they say, all over the place. Well, nearly. Despite the title of this exhibition, he never so much as lifted a paint brush during his three-year stay in Britain.

The then 20-year old Dutchman arrived one weekend in May 1873, having been sent to London by his employer, the art dealer Goupil. At this point in his life Vincent was more interested in selling art than making it (although he drew a lot). If anything, he was more inclined to follow in his father's footsteps and become a preacher. Or, failing that (which he did), a teacher (also attempted, not a success).

But, unbeknownst to him, all those walks along the Thames he so loved to take with a Charles Dickens tome in his pocket and a top hat on his head ("You couldn't be seen in London without one"), were quietly informing his future artistic sensibilities. Britain was priming Van Gogh's canvas.

Sao Paulo Museum of Art

Sao Paulo Museum of Art

At least, that's what this exhibition argues. And does so convincingly, comparing paintings he would later produce with those he saw in museums and galleries while living in Brixton. For instance, on one wall hangs Meindert Hobbema's The Avenue at Middleharnis (1689), a National Gallery painting that had caught Vincent's eye. While on the opposing wall hangs his own Avenue of Poplars in Autumn (1884).

It's not exactly a facsimile, nor is a receding line of trees a motif previously unknown to Van Gogh, but there's enough of a similarity to suggest an influence.

A more compelling case is made with Starry Night, which is presented alongside two other artworks: James Whistler's atmospheric Nocturne: Grey and Gold, Westminster Bridge (1871-2), and Gustave Doré's Evening on the Thames (1872). Vincent has clearly noted compositional elements from both images, but more than that, there is the romantic, twilight atmosphere shared by all three pictures, which pull you towards them like a cool drink on a hot night.

1. When Van Gogh was in London he would stop and look as this view painted by James Whistler on his way home, standing for a while and drawing it for pleasure.

2. Vincent bought this print of an Evening on the Thames by Gustave Doré after he left Britain. The nocturnal mood it captures is evident in Van Gogh's Starry Night.

3. It is clear when seen together that Vincent was heavily influenced by both Whistler and Doré. You can detect similarities across all three in terms of composition, light effects on the water, subject, and time of day.

The mood changes as you make your way through the show.

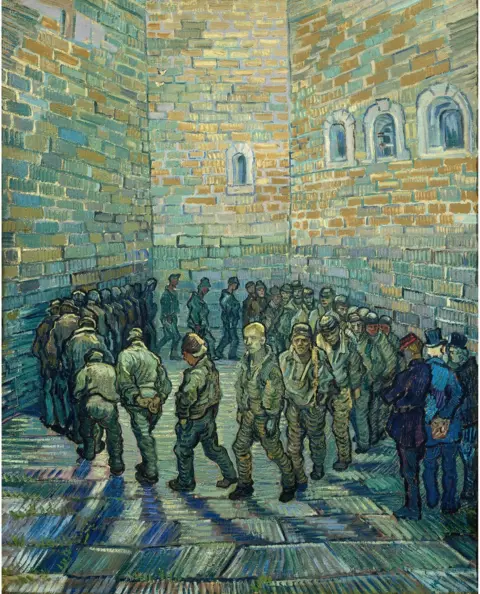

Sensual evenings give way to anxious old men and prisoners in an exercise yard. The match-ups continue and with them more and more elaborate examples of how Britain was the making of Vincent van Gogh. Frankly, you could construct the same argument about his time in the Netherlands or France. At least, you could for the first half of the show, which is about how a country influenced him. But not for the second part, which focuses on how he influenced Britain.

Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

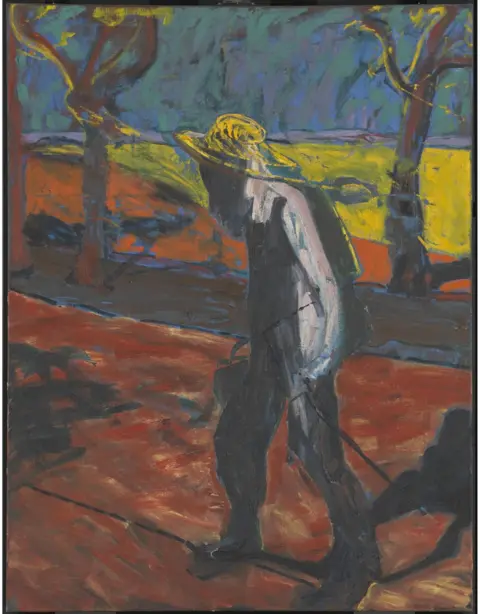

We know that David Hockney is a big fan. So much so, in fact, that there is currently a Hockney show at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. But he doesn't make the cut in the Tate's exhibition, which concentrates on earlier 20th Century British artists like Walter Sickert, Winifred Nicholson, and - most powerfully - Francis Bacon, who once said about the flame-haired painter from Zundert:

"Van Gogh speaks of the need to make changes in reality, which become lies that are truer than the literal truth."

There is a room dedicated to showing Bacon's three magnificent responses to Van Gogh's lost canvas, Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888). They should be a wonder to behold, an exhibition highlight from which you can stand back and breathe in.

But they are not.

The experience of seeing them is compromised by an annoying television screen on the left-hand wall showing a clip from Vincente Minnelli's 1956 Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life.

There's nothing wrong with the movie, Kirk Douglas turns in a decent Vincent, but to have its distracting flickering presence in a dark-walled gallery dedicated to three important paintings by Britain's greatest - Van Gogh-inspired - expressionist painter is a crime against art and curating.

It is such an insensitive thing to do.

There's plenty of space outside the gallery to put the screen. Stick it anywhere, just leave the art alone.

Estate of Francis Bacon

Estate of Francis Bacon

There is another audio-visual intervention earlier in the show - again too near a major work (Augustine Roulin, Rocking a Cradle). It is marginally less irritating but still an unwelcome presence. I thought budgets in museums were supposed to be tight and tech expensive. Get rid of it, save the money and reduce the ticket price.

The more people who can see the exhibition the better: it is a cracking show boasting one superstar, an excellent supporting cast, and an ingenious narrative that could well be made into a movie - to be seen in a cinema not in an art gallery.

National Gallery of Art, Washington

National Gallery of Art, Washington