How the food of Charles Dickens defined Christmas

BBC

BBCCharles Dickens was a serious foodie and his literature introduced a festive menu that has barely changed since the Cratchits gathered round their table in A Christmas Carol.

"The thing about Dickens," says food historian Pen Vogler as she takes a tray of caraway seed biscuits out of the oven, "is that he knew what it was like to be hungry."

She's explored how cuisine shaped his writing in her recipe book, Dinner With Dickens. In it she recreates dishes that the literary giant wrote about, and shows how he used food to create character and comedy but also highlighted social issues.

She's also whipped up a Christmas pudding but thankfully has avoided making gruel.

CICO Books

CICO Books"Dickens did not have food security as a child," continues Pen as she slips the steaming biscuits onto a wire rack to cool.

"His novels often contain innocent, hungry children - he wanted to show readers that good food and nourishment were a human right, even if you were poor."

When Charles Dickens was 12, his father was imprisoned for debt and while the rest of the family went to live with him in prison, Charles was sent to work in a blacking factory where he had to manage his tiny wages to buy penny buns and bread to eat.

His interest in food, says Pen, stems from this time.

In his writing, his characters' attitude to food often gives us clues to their morality. Fat adults often starve thin children; characters who share and enjoy lavish feasts are good, characters who make lavish food just for show or who waste food are generally bad. Think Miss Havisham's wedding cake….

"If the right emotional feelings are not there, it is worse than worthless," says Pen. "Food's got to be enjoyed in the right way and appreciated. Food for him was much more emotional than showy."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCharles Dickens was a serious foodie (check out his leg of mutton stuffed with oysters) who was famous for his generous dinner parties; his wife Catherine even published a little book of recipes to suit all budgets.

"If Dickens had been alive today," muses Pen as she chops apples, "I could definitely see him judging Bake Off, although he was much more of a savoury man than a pudding man."

She grates some nutmeg. "There are very few cakes and puddings in his writings except in the autobiographical David Copperfield where he remembers the sweet tooth and treats of childhood."

Pen's little black cat watches attentively from the floor as she stirs currants into her Christmas pudding mix. She tips in a very generous amount of brandy.

"Dickens loved a drink!" she says. "He even sent a recipe to a friend for punch so we know exactly how he made it - and his characters drink it all the time! He also drank champagne and claret for celebrations and things we've lost the taste for like purl, flip, dog's nose and wassail."

CICO Books

CICO BooksIn 1843, Dickens published A Christmas Carol, which contained the famous scene of the Cratchits contentedly gathered round the crackling fire with their goose, apples and oranges, chestnuts and the "speckled cannon ball" pudding.

With his emphasis on a family gathering, believes Pen, Dickens set the template for today's Christmas celebrations.

"Until the publication of a Christmas Carol," says Pen, "Christmas pudding was known only as plum pudding - but after that, plum pudding was afterwards always referred to as Christmas pudding… and if you think about it, our Christmas menu hasn't changed since the Cratchits!"

Leg of Mutton Stuffed with Oysters

Young John Chivery, son of the Marshalsea Turnkeeper, is rewarded for running "mysterious missions" with a banquet, for which Miss Rugg "with her own hands stuffed a leg of mutton with oysters." Dickens invited Daniel Maclise to share the same dish before a night walk through the slums (letter, November 20, 1840), and later invented his own twist, adding veal to the stuffing, served at the office of his journal, Household Words.

SERVES 6-8

2 tablespoons freshly chopped flat-leaf parsley

1 dessertspoon freshly chopped thyme leaves

1 dessertspoon freshly chopped savoury

2 hard-boiled egg yolks

6 oysters, cleaned, shucked, and chopped, reserving the liquor, or 6 finely chopped anchovies

3 garlic cloves, minced (I think garlic is better than onion in this dish, but if you prefer to follow Catherine, use one very finely chopped shallot)

leg of mutton (or lamb if you cannot find mutton), approx. 5½-6¾ lb/2.5-3kg

2 teaspoons all-purpose/plain flour

1¼ cups/300ml lamb or chicken stock

Preheat the oven to 425°F/220°C/Gas 7.

Chop the herbs as finely as possible - a meat cleaver is useful for this. Bind them together with the egg yolks, oysters (or anchovies), and garlic (or shallot).

Using a sharp knife, make about 6 indentations in the fleshy part of the leg of mutton (or lamb) and push in the mixture. If you make the indentations at a slight angle, you can pull the fat back over the cut.

Place the meat in a roasting pan and roast in the preheated oven for about 30 minutes, then turn the oven down to 325°F/160°C/Gas 3. Baste the joint with the fat and juices in the pan and continue roasting for 15-20 minutes per 1 lb/450g.

When the meat is done, remove it from the oven, cover with foil, and let it rest for 15-20 minutes.

Make the gravy by mixing the flour with the fat in the roasting dish over a low heat, and slowly adding the stock and the oyster liquor. Skim the fat off the gravy (putting it in the freezer helps it coagulate on the top) and serve as it is, or add to the Piquant Sauce ingredients

PIQUANT SAUCE

1 shallot, finely chopped

a little oil

1 tablespoon finely chopped gherkins

1 tablespoon finely chopped capers

4 tablespoons good red wine vinegar

1 anchovy fillet, pounded

Sweat the shallot in the oil until it softens, then add the gherkins, capers, and vinegar. Simmer for 4 minutes.

Make gravy from the joint, add the oyster liquor (to make about 1¼ cups/300ml), the shallot mixture, and the pounded anchovy. Simmer for a few minutes before serving in a gravy boat.

"Adult hunger is dangerous in Dickens," warns Pen as she puts the kettle on for tea.

In A Tale of Two Cities, adult hunger leads to riot and revolution, and in Great Expectations, the hungry Magwitch, an escaped convict, is dangerous and frightening to young Pip who must steal food for him.

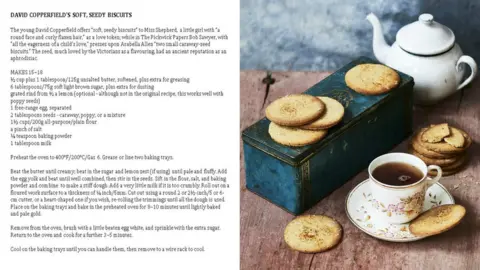

The seedy biscuits are delicious - the same kind that the young David Copperfield offered to a little girl he had fallen in love with as a token of his esteem- and they go beautifully with our Darjeeling tea.

Pen has worked out that good characters take tea in Dickens' work while the slightly dubious ones tend to drink coffee.

Under the circumstances, it seems only polite to pour another cup and have another soft seedy biscuit...

You can hear more on BBC Radio 4's Broadcasting House programme on Sunday 24 December from 09:00 GMT.

Follow us on Facebook, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.