Review: Bryan Cranston stars in Network at The National Theatre ★★★☆☆

BBC

BBCTo say Ivo van Hove's stage adaptation of Paddy Chayefsky's 1976 movie Network is a bit gimmicky would be like describing the Arctic as a bit chilly.

There are more production bells and whistles in his 119-minute (no interval) show than on one of Lady Gaga's more outré outfits.

The Belgian director and his designer Jan Versweyveld have turned the National Theatre's expansive Lyttleton stage into a shiny contemporary landscape with a massive screen acting as a backdrop for a set, divided into three principal components.

They are: A glass box TV production gallery, a newsroom studio (centre-stage), and a Manhattan-style restaurant and bar (at which audience members can book a table if they're willing to take out a small mortgage).

It looks great and very glitzy. A stage set for some genuine A-list stars to come and entertain us. Which they do.

NAtional Theatre

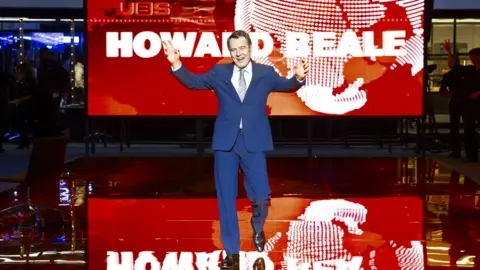

NAtional TheatreFirst, Bryan 'Heisenberg' Cranston appears as Howard Beale, an old-time news anchor getting rubbish ratings who - not unlike Walter White in Breaking Bad - undergoes a dramatic character transformation (he even strips down to his underpants again - although not tighty whiteys on this occasion).

While White became a very good baddie, Beale turns into a deranged TV prophet, telling his viewers he is as "mad as hell" about media cover-ups and political corruption.

The crazier he becomes, the higher his ratings soar. Enter Michelle 'Lady Mary' Dockery as a ruthless TV exec out to milk his madness for every percentage point of audience share she can.

It is a play about a ratings-obsessed media, corporate cynicism, corrupting commercialism, and the dangers of fanaticism. It is, in other words, a play for today.

At least, it should be. But despite the largesse that has been lavished on this production, it is rather two-dimensional and a tad disappointing.

National Theatre

National TheatreFrom the moment you enter the theatre and see the stage you sense you are in for something very special - a night to remember; a glamorous theatrical blind date.

But, by 15 minutes in, ardour turns to apathy as it becomes apparent the cast and crew were having way more fun than you.

The problem is the directorial conceit. On-stage TV cameras relay much of the action we see onto the giant screen at the back. It's a device that works at a rock concert in an arena where the performers are barely-visible far off figures.

But in the more intimate environment of a theatre, where you can see and hear the actors, it has the opposite effect and actually makes the players feel more distant.

The delay in the on-screen lip-sync doesn't help. Not only is it annoying but also ruinously distracting. I started to worry about whether or not my car was due for its MOT.

National Theatre

National TheatreThere are other smaller niggles. Like, why is there a fancy restaurant on the stage? To create another location for the actors and the story, I assume.

But why? If Shakespeare can ask us to imagine whole battles taking place "within this wooden O", then surely we can be trusted to imagine a restaurant scene without a fully functioning bar and brasserie.

And why, in a narrative so specifically set in America, is the action momentarily taken outside the building and onto London's Southbank with the National Theatre's illuminated logo in full view?

We get the idea that the audience's perception of what is real and what is fantasy is being toyed with, but it diminishes rather than enhances the action. There's no point to it.

Perhaps the director wasn't confident enough in the script and felt the need to dress it up like a stag party at a Dolly Parton convention. And, if so, I have some sympathy for him.

Lee Hall is magnificent writer, who has consistently produced outstanding scripts. But, on this occasion, he has missed an opportunity to explore and update the central themes inherent in the original film.

Doug Hyun/AMC

Doug Hyun/AMC Maybe it is due to an understandable reverence for the movie, or because it was technically impossible to do so. Or he didn't want to.

Any which way, the light he shines on the nature of television news, undue corporate influence, and a culture of populism is too warm and a little weak. Any blows landed are glancing rather than knock out.

The point that newscasts are a form of entertainment is as old as the movie, what's new is how a certain type of media operator has been able to exploit that weakness for world changing political gain.

The airtime devoted to big personalities, sometimes in stark contrast to their relatively low political status, has given rise to quick-fix merchants proffering simplistic solutions to a dispirited public who have then voted in their favour.

Howard Beale is not a good guy. He's demented and arrogant and egotistical. And all the more so when he discovers the elixir of popular appeal. He's no better than other hyperbolic narcissists plying the opinions on news programmes around the world.

But in this play he's let off the hook. He is allowed to become a preachy, saintly figure. And thereby the profound prescience of Paddy Chayefsky's Network is lost.

Follow us on Facebook, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected].