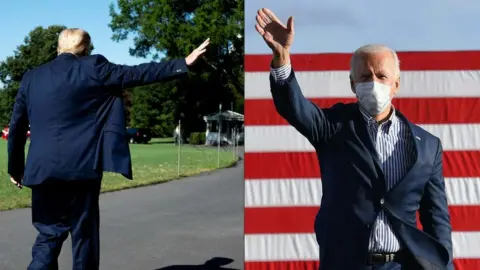

Biden inauguration: How the White House gets ready for a new president

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe last vestiges of the Trump presidency will be swept away on Wednesday, as the Bidens move into the White House. Desks will have been cleared out, rooms scrubbed clean and the president's aides will be replaced by a new team of political appointees. It's part of the massive transformation that a new presidency brings to the heart of government.

One evening last week, Stephen Miller, a policy adviser and central figure in the Trump White House, was lounging in the West Wing.

Miller, who has crafted speeches and policies for the president since his early days in office, is also one of the few members of the president's initial team still with him at the end.

Leaning against a wall and chatting with colleagues about a meeting scheduled for later that day, he seemed in no hurry to leave.

The West Wing usually hums with activity but it seemed deserted. The phones were quiet. Desks in empty offices were cluttered with papers and unopened letters, as if people had left in a hurry and would not be coming back. Dozens of senior officials and aides quit in the wake of the Capitol riots on 6 January. A handful of loyalists, like Miller, remain.

As the conversation began to wind down, he broke away from his colleagues. When I asked him where he was headed next, he smiled. "Back to my office," he said and sauntered down the hall.

'It's very rocky'

On inauguration day, Miller's office will have been cleaned out, swept of signs that he and his colleagues had ever been there, ready for the Biden team to move in.

The cleaning out of West Wing offices, and the transition between presidents, is part of a tradition that dates back centuries. It's a process that has not always been imbued with warmth.

Another impeached president, Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, snubbed Republican Ulysses S Grant in 1869 and skipped the inauguration. Grant, who had backed Johnson's removal from office, was hardly surprised.

This year, however, the transition stands out for its acrimony. The process usually starts straight after the election, but it started weeks late after Trump refused to accept the result. And the president has said he will not attend the inauguration. Most likely, he will instead travel to his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida.

Still, the handover is taking place, just as it has in the past. "The system is holding," says Sean Wilentz, a professor of American history at Princeton University. "It's very rocky, it's very bumpy, but nevertheless the transition is going to occur."

Even in the best of times, the logistics of a transition are daunting, involving the transfer of knowledge and employees on a massive scale.

Stephen Miller is just one of 4,000 political appointees hired by the Trump administration who will lose their job and be replaced by individuals hired by Mr Biden.

During an average transition, between 150,000-300,000 people apply for these jobs, according to the Center for Presidential Transition, a nonpartisan organisation based in Washington. About 1,100 of the positions also require Senate confirmation. Filling all of these positions takes months, even years.

Four years of policy papers, briefing books and artefacts relating to the president's work will be carted off to the National Archives where they will be kept secret for 12 years, unless the president himself decides that portions may be released early.

Moving day

On a weekday evening during Trump's last week in office, the door to the office of Kayleigh McEnany, the president's press secretary, was partly open.

McEnany has been one of the president's most high-profile defenders. Impeccably groomed, she is a precise speaker who maintains her composure amidst chaos.

Reuters

ReutersHer office, too, was organised in a meticulous manner, even as she prepared to leave. A mirror stood on her desk, and several fireplace logs were wrapped in clear plastic and packed up.

Generally, the last few days are "controlled chaos," says Kate Andersen Brower, who has written a book about the White House, The Residence.

Furniture in the White House, such as the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office, most of the artwork, china and other objects, belong to the government and will remain on the premises.

But other items, like photos of the president that hang in the hallway, will be taken down as the White House is transformed for its new occupants.

Staffers are already moving some items out of the building. One White House staffer, a woman in sturdy heels, was lugging several images of First Lady Melania Trump out of the East Wing. The pictures are known as "jumbos" because of their extra-large size, she says, and they will be taken to the National Archives.

The Trumps' personal belongings, such as clothes, jewellery, and other items will be moved to their new residence, most likely at Mar-a-Lago in Florida.

And this year, the place will be deep cleaned.

Reuters

ReutersThe president, as well as Mr Miller and dozens of others at the White House, were infected with the coronavirus over the past several months, and the six-floor building, with its 132 rooms, will be thoroughly scrubbed down. Everything from handrails to elevator buttons to restroom fixtures will be wiped and sanitised, according to a spokeswoman for the General Services Administration, the federal agency that oversees the housekeeping effort.

Incoming first families usually do some redecoration. Within days of arriving at the White House, Mr Trump had chosen a portrait of populist president Andrew Jackson for the Oval Office. He also replaced the drapes, couches and a rug in the office with ones that were gold-coloured.

On inauguration day, Vice-President Pence and his wife will also make way for Kamala Harris, and her husband, Doug Emhoff. They will be settling into their official residence, a 19th Century residence on the Naval Observatory grounds, a couple of miles from the White House.

Closing a chapter

Policy adviser Stephen Miller may have lingered in the West Wing, but others were ready to go. At the White House, people were lugging thick manila envelopes, framed photos and bags from a gift shop. "It's my last day," says one man, smiling as he took a photo of his sons on the north lawn. A bulging backpack was slung over his shoulder.

A group of National Security officials posed in front of the West Wing, asking me to take their picture. "Make sure you get the marine guard," says one of the officials, referring to a marine who stands in front of the doorway when the president is in the Oval Office. The officials were in high spirits, joking and vamping for the camera.

The political appointees at the White House were in a good mood for a reason. For weeks, they had been caught in an in-between world. Their boss was denying the validity of the election, but they knew that their days were numbered. Now they could plan openly for their future, and they seemed almost giddy.

One political appointee, a man dressed in a dark suit, was already making plans. He ran into a colleague outside the Palm room, a reception area on the ground floor. "See you on the flip side," he said, brightly. He was referring to the time after the inauguration, when they will both be out of their White House jobs. He mused about where they might meet again. "Hopefully in the Greek isles or somewhere."

"Oh, yes. That is for sure," said his colleague, laughing. They smacked a high-five and then parted ways.