US Election 2020: The 'dead voters' in Michigan who are still alive

Roberto Garcia

Roberto GarciaDonald Trump's supporters have claimed that thousands of votes were cast in the US election using the names of people who had died.

"I may be 72," Maria Arredondo from Michigan told us when we called her. "But I'm alive and breathing. My mind is working fine and I'm healthy."

Maria said she had voted for Joe Biden and was surprised to hear that her name had appeared on a list of supposedly dead voters in the state.

We spoke to other people in similar situations to that of Maria in Michigan and found similar stories.

There have been occasions in previous US elections of dead people having apparently voted.

This could happen through clerical errors or perhaps other family members with similar names voting with their ballots, but Trump supporters have alleged this has happened on a massive scale at this election.

We set out to find out whether there is evidence for this claim.

10,000 'dead absentee voters' in Michigan?

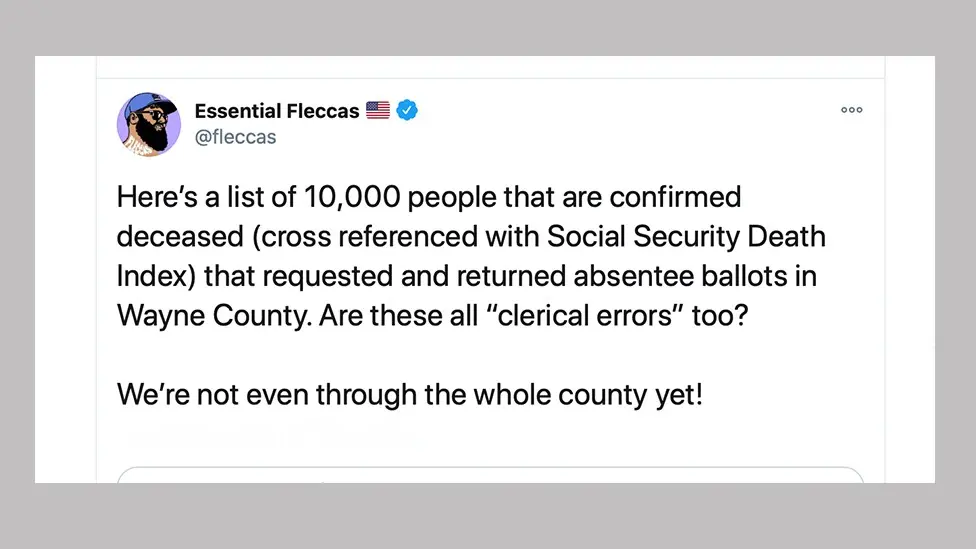

The story starts with a list of around 10,000 names posted on Twitter by a Trump-supporting activist.

It purports to be of people who have died, but who have also voted in the presidential election in Michigan.

Claims such as this have been repeated many times on different social-media platforms, including by Republican legislators.

The list of 10,000 contains the name, zip code, and the date a ballot was received. It then lists a full date of birth and a full date of death. Some of the people supposedly died more than 50 years ago.

Michigan has a database that lets you enter someone's name, zip code, month of birth and year of birth and allows you to see if they voted by absentee ballot this year. So you can easily check whether people on the list voted.

There are also several US websites that include databases of death records.

But there's a fundamental problem with this list of 10,000.

With an exercise like this you are going to find false matches - somebody born in January 1940 voted in Michigan in the election, and there was somebody born somewhere else in the US in January 1940 who has the same name and is now dead. This will happen a lot in a country as big as the US (328 million people), and particularly with common names.

To test the list, we picked 30 names at random. To this we added the oldest person on the list.

Of this list of 31 names, we managed to speak directly to 11 people (or to a family member, neighbour or care home worker) to confirm they were still alive.

For 17 others, there was no public record of their death, and we found clear evidence that they were alive after the alleged date of death on the list of 10,000. A clear pattern emerged - the wrong records had been joined together to create a false match.

Finally, we found that three people on the list were indeed dead. We examine these cases later.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat we discovered

The first thing we did was to check the official Michigan electoral database to see whether our 31 individuals had sent in ballots - they all had.

We then looked at the death records and quickly became suspicious on seeing that the vast majority did not die in Michigan, but elsewhere in the US.

We wondered whether we could find people of the same name currently living in Michigan.

Checking Michigan state public records, cross-referencing voter postal codes, we were able to find precise dates of birth for those who had voted - and as we had anticipated, they failed to match the dates of birth on the death records.

So we could be confident that we were dealing with two sets of people - those who had voted and those with the same name and age who had died elsewhere.

But what we really wanted to do was to speak to the voters themselves.

'I'm alive!'

We called Roberto Garcia, a retired teacher in Michigan. He told us: "I'm definitely alive and I definitely voted for Biden - I would have to have been dead to vote for Trump."

We also found a 100-year-old woman who, according to the "dead voter" list, had died in 1982. She was alive and is currently living in a nursing home in Michigan.

But the results of our search weren't always so straightforward.

When we looked for another centenarian, who according to the list had died in 1977, we found that she had still been alive when her postal ballot was returned in September. However, a neighbour told us the woman had died just a few weeks ago. We also found a matching obituary from October to confirm this.

If a voter dies before election day after submitting their ballot, the Michigan authorities say the ballot will be rejected.

We have not been able to establish whether her ballot was counted.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor those we couldn't reach by phone, we wanted to use other means to confirm they were alive.

These included public records of, for example, business activities, from state and local authorities.

For one woman who was supposed to have died in 2006 we found an annual company statement signed under her name from January 2020.

Two other men on our list of 31 died some time ago, yet votes had been cast in their names - with the correct postcodes and years of birth - according to the voting database.

We found that for both men, there were sons with the same name currently registered at the same address as their deceased fathers.

In both cases, a ballot was sent in for the dead fathers.

Local election officials told us that one of the votes had been counted but there was no record of the son having voted.

In the other, it was the son who actually voted, but it had been recorded as the father's due to a clerical error.

Getty Images

Getty Images'It's simply a matter of statistics'

Our selection of 31 cases is only a small sample of the 10,000 names on the list, but it has clearly revealed the flaws in the database shared by Trump supporters.

From our investigation it's clear that in almost all of our 31 test cases, the data for genuine voters in Michigan has been combined with records of dead people with the same name and birth month and year from across the United States to yield false matches.

"If the lists are linked based on name and birth date alone, in a state the size of Michigan, you're guaranteed to get false positives," says Prof Justin Levitt, an expert on the law of democracy.

It's known as the birthday problem - the high probability that two students in the same class share the same birthday.

So if you compare millions of voters in Michigan with a database of deaths across the United States you're bound to find cross-over, particularly if the voter database doesn't include the day of the month on which a person is born.

"It's simply a matter of statistics that if you cross-reference millions of records with millions of other records, you'll get a sizable number of false positive matches. We've seen this before," says Prof Justin Levitt.

With her vote safely cast, and counted, Maria Arredondo tells us she's looking forward to the new administration.

"He was a great vice-president under Obama. I'm so pleased. A weight has lifted off my shoulders."