US 2020 election: Who does China really want to win?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUS presidential elections have long been a source of both intrigue and irritation for China's Communist Party rulers.

As arguably the most consequential exercises in democracy on the planet, they are always closely followed by government officials in Beijing.

But as potential reminders of just how little choice 1.4 billion people are given over their own political future, media coverage in China is tightly controlled.

This time round though, in a US election defined by a still spiralling pandemic, a shattered economic landscape and deep political polarisation, China senses that something has changed.

It is not Chinese authoritarianism but Western democracy that suddenly seems to be facing a crisis of legitimacy.

The world's freest and wealthiest economy, once thought to be so much better placed to fight the virus with its tools of transparency and accountability, has fallen well short.

While China, despite an initial cover-up thought to expose its inherent weaknesses, has gone on to use the sweeping powers of a unitary, surveillance state to test and quarantine people at will, en masse and to great effect.

Factories, shops, restaurants, schools and universities are all open, passenger numbers on public transport are just a little below average, and it is the only major economy expected to grow, rather than shrink this year.

This has all been done in the absence of any public debate - in fact, heavy censorship has ensured quite the opposite - and without anyone ever being allowed to cast a meaningful vote for or against any decision maker, at any level of government.

The sense that something fundamental is at stake, with the disparity now bringing into sharp relief not the weaknesses of China's political values but their superiority, goes right to the very top.

"The major strategic achievement gained from China's fight against Covid-19 fully demonstrated the remarkable advantages of the leadership of the Communist Party of China," President Xi Jinping said last month at an event to celebrate the health workers and "heroes" of this triumph.

It is a message being rammed home in state-TV news bulletins full of sombre statistics charting America's unfolding health disaster alongside images of the protests, dissent and disarray of the election campaign.

It doesn't matter who wins, the subtext seems to read, when the American body-politic is sick, its limits laid bare and its power and prestige waning on the world stage.

There are few better visual metaphors for China's growing confidence in its system than the bright lights and glitzy consumerism of this month's Beijing Car Show.

It is also a good vantage point to ponder an era when economic co-operation was supposed to supplant ideological confrontation in its relationship with America.

The event, held in a sprawling exhibition complex, is the world's first major auto industry show since the pandemic began, a testament to this country's victory over the virus.

Apart from the masks, it is like a scene from a pre-virus age.

The merchandise-clutching public throng around the trade stands, posing for photos with - in fact, perhaps think more pre-Stone Age here - the models in tight-fitting dresses standing next to the cars.

But if the show is a sign of China's ability to stem the tide of a pandemic it is also proof of something much deeper and longer-term; its ability to channel the forces of global trade to its advantage.

One of the most expensive cars on display is a bright green, all-electric SUV - price tag 550,000 Chinese Yuan ($80,000) - made by Hongqi, a Chinese manufacturer once famed for its sedate, Soviet-style limousines.

"We should support the brands our own country makes," one man tells me, examining the leather trim of the front passenger seat.

It's a symbolism that would not have been lost on Richard Nixon, the US president who launched America's rapprochement with China.

On his historic visit to Beijing in 1972, he was driven in a traditional Hongqi along roads devoid of traffic - the start of a journey of engagement between the two nations that would continue for more than 40 years.

Almost every US president since has bought into the idea that it was not only of benefit to China and the multinational corporations making profits there, but also to America and the wider world.

It wouldn't just boost overall global prosperity, it was argued, but it would bring China into the liberal global order and even encourage it to embrace the possibility of political reform at home.

In reality, China saw it very differently, driven by the singular objective of reclaiming its rightful place on the global stage and on its own terms.

By the time of the 2016 US election, it was the world's second largest economy and its biggest exporter.

Yet it also stood accused of the biggest theft of industrial secrets in human history and was about to embark upon probably the largest mass incarceration of an ethnic group since World War Two.

It was in that 2016 campaign that the already fraying consensus about the wisdom of ever-increasing trade and engagement with China finally broke.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRunning for his first term, Donald Trump's message to his blue-collar base was that a fiercely protectionist China had long been cheating on its free-trade commitments to turn itself into an economic superpower.

In terms of lost jobs, he argued, it had left US workers worse off, not better.

He rode that message all the way to the White House and nothing has been the same since.

The president's tit-for-tat trade war, at its peak, saw a total of $362bn of goods subjected to punitive tariffs.

This year, his administration has added to the economic pressure with a barrage of political sanctions over China's human rights abuses.

With some of the beneficiaries of one-party rule still eyeing up the shiny green, made-in-China SUV at the Hongqi trade stand, I ask one of them who he wants to win the US election.

"Maybe Biden," he says, adding, "I hate Trump."

"Because he's been so hard on China?" I enquire.

"A little," he replied, "and I think he's crazy."

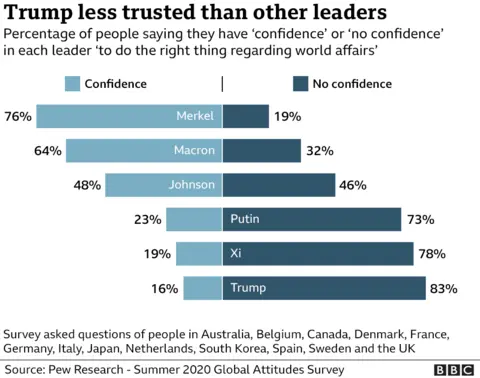

Chinese leaders may have a growing feeling that US democracy has passed its sell-by-date but if they had to express a choice, might they too be glad to see the back of Donald Trump?

That's certainly the assessment of the US intelligence community that has concluded that Mr Trump's unpredictability, and his harsh criticisms of Beijing, mean the Communist Party leadership would prefer him to lose.

But Professor Yan Xuetong, dean of the Institute of International Relations at Beijing's Tsinghua University, disagrees.

"If you ask me about where China's interests lie," he says, "the preference would be for Trump rather than Biden".

"Not because Trump will do less damage to China's interests than Biden, but because he definitely will damage the US more than Biden."

It is a sign of just how far things have deteriorated from the idea of closer economic ties for mutual benefit.

Distinguished Chinese observers are now prepared to state openly that the decline of the US, both economically and politically, is in China's interests as a rising power.

While some observers have suggested that China's belief in the end of US global dominance predates both the virus and President Trump, what has changed is its readiness to spell it out.

From this perspective, Donald Trump is the better option, not because of his support for democratic ideals, but precisely because he is often seen to reject or undermine them.

His attacks on the free press, for example, have been music to the ears of a Chinese state deeply hostile to independent scrutiny and intent on bending the internet even further to its will.

And while his administration has grown increasingly critical of China over human rights, his own motivations appear to be driven by far narrower considerations of trade and economic advantage.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to his former National Security Adviser, John Bolton, Mr Trump once told Xi Jinping that he approved of his draconian crackdown on the Uighurs, although the president has denied the claim.

While he mocks Joe Biden's previous support for closer economic ties with China, in comparison it may be Mr Biden who Beijing fears will do more to stand up for democratic values.

Mr Biden is also much better placed than the isolationist Mr Trump to repair the bridges with democratic allies and build coalitions to pressure China over its treatment of its own people.

Christian Ji is one of the casualties of what some US academics see as a xenophobic shift in Washington's approach; the targeting of Chinese students.

An exchange student studying computer science in Arizona, last month Mr Ji had his visa revoked as part of an entry ban imposed by Washington on hundreds of Chinese researchers from universities with links to the military.

His visa was later reinstated because the promulgation, which is drafted to exclude undergraduates, was wrongly applied to him.

But although the experience has left him angry at President Trump, it has not changed his view of America.

"I really like the environment in the US," he told me when we met in a Beijing teahouse.

"The pollution is less than in China, and the education is more based on thoughts. In China, it's more focused on right or wrong."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's a reminder that despite China's growing confidence that Western democracy is in crisis, American values are still respected by many here.

If the beacon of democracy really is losing its lustre, why then you might wonder, were there 360,000 Chinese students in the US in 2018, 30 times more than the number of US students in China?

China's propaganda effort to portray the vanquishing of the virus as proof of the advantages of its system should not be taken at face value.

The country's leaders well know that a number of democracies have also successfully brought the virus under control; Japan, New Zealand and South Korea, to name just a few.

Even for those that are seriously struggling, some observers believe there is still reason for optimism about the ability of open societies to eventually learn, adapt and correct.

And while the protection of individual rights may make controlling an epidemic that much harder, a system where people can be "handcuffed to their homes" is unlikely to be a public health utopia.

So China's belief that the virus is helping hasten the arrival of a 'multi-polar' world - one in which its authoritarian norms are given equal weight to democratic ones - may be more wishful thinking than historical prediction.

Ironically, a US president who reaffirms his belief in the liberal world order and returns to the world stage might be far better for China in the short term.

Joe Biden may well be promising to push it on human rights and - in a sign of just how far the consensus has now shifted in Washington - calling Xi Jinping "a thug".

But he may take a softer line on tariffs and he'd be far more willing to look for co-operation on issues like climate change, which China could potentially leverage and use to its advantage.

China's rulers, though, aren't thinking in terms of electoral cycles, they're contemplating the end of an epoch.

And an America reasserting itself as the champion of universal values - the reappearance of the shining city on a hill - is exactly what they fear the most.