General election 2019: Does Labour need a new direction after Corbyn?

BBC

BBCLabour's lost its fourth general election in a row. And it will soon have a new leader. But will this be enough to get it back into government?

The ground was soggy underfoot.

I perched on a grassy knoll on the outskirts of Middlesbrough on the eve of poll.

It was the perfect vantage point for surveying the turnout at one of Jeremy Corbyn's last campaign rallies, in an adjoining open-air car park.

This was a far cry from the mass rallies I had seen in the 2017 campaign - but, to be fair, it was a week day and it was freezing.

But it wasn't the enthusiasm of the hardy activists that was in question, but the loyalty of Labour voters who had voted to leave the EU.

I was hearing they were also about to leave behind their traditional party loyalties, despite party chairman Ian Lavery declaring at the rally: "This election has nothing to do with Brexit."

I was told that seats which had been Labour since their creation - such as Blyth Valley - could fall.

Local and regional activists, however, were hoping the North East of England would be unduly disastrous for the party and that other areas would fare better.

But I was also being told of problems in the West and East Midlands and, 24 hours later, the dire predictions proved accurate.

Indeed, the final result nationally was worse than insiders feared.

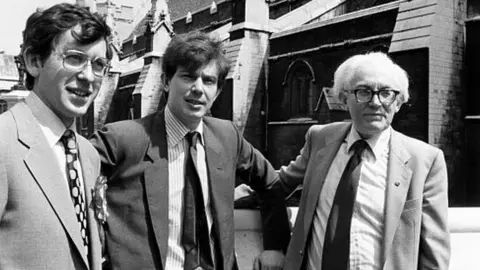

PA Media

PA MediaWell placed sources thought Labour would suffer a net loss of seats but wouldn't fall below 230. The more pessimistic confided a figure of 220.

In the end, with 203 seats, it was a worse parliamentary haul than Michael Foot's post-war low in 1983.

The immediate battle now is over the narrative of why Labour lost.

He or she who controls the past controls the future.

So that's why shadow chancellor John McDonnell was quick out of the traps to blame the defeat on Brexit.

No need to search for wider difficulties, or to change the party's direction.

The grassroots movement he formed with Jon Lansman - Momentum - declared it would "keep Labour socialist".

The policies were popular; it was just that the wider public hadn't fully appreciated this.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf this narrative wins, it would help clear the ground for another leader from Mr Corbyn's wing of the party.

Some close to Mr Corbyn hoped that would be shadow minister Laura Pidcock, but the public begged to differ and ejected her from her Durham seat.

So the current favourite on the Left is shadow business secretary Rebecca Long-Bailey. When Mr McDonnell says the next leader should be a woman, he is almost certainly thinking of her.

But other candidates and therefore other narratives are available.

Defeated parliamentary candidates, such as Phil Wilson in Sedgefield, Tony Blair's old seat, and Ruth Smeeth, in Stoke, have pointed out that Mr Corbyn's leadership came up on the doorstep more than Brexit.

The party's former general secretary, Lord McNicol, has said the problem isn't so much Corbyn as what he called "Corbynism" - the move of the party to the left, with a narrower group of less experienced MPs in frontbench positions, and an offer of change that may have seemed too radical for some former supporters.

Reuters

ReutersIf a wider review of the party is on the agenda - a change of direction, not just a change of leader - this could help hopefuls such as Sir Keir Starmer and Emily Thornberry. Sir Keir was never quite trusted by the leadership but the pro-Remain membership has been impressed with him as shadow Brexit secretary. A quick contest would suit him, but Mr Corbyn seems in no rush to go.

Some MPs are muttering that they may even mount a challenge - which needs a fifth of the parliamentary party - if his "period of reflection" begins to stretch in to a lengthy meditation.

Reuters

ReutersAnother potential candidate who would move the party away from the Corbyn era is Jess Phillips. Many of the membership may believe she'd try to move the party to the centre, though in the Blair years she would have been regarded as "soft left".

But her supporters hope, in a contest, she would encourage non-members to sign up as "registered supporters" (as happened with Mr Corbyn's unanticipated victory in 2015) and re-shape the party as a more social democratic entity, but led by someone who doesn't look or sound like a conventional politician and who may be a match for that other big personality, Boris Johnson.

But the election post-mortem won't all be about leadership manoeuvring.

I have had activists and insiders complain about the organisation as much as the politics.

One source said: "We need to look at why we were sending hundreds of people to Boris Johnson and IDS's (Iain Duncan Smith's) seats, which we couldn't win, when canvassing sessions elsewhere were being cancelled for a lack of volunteers."

While Momentum tried to divert resources to certain seats, critics say the party itself lacked coherence

Some unions are irritated that they never got a list of target seats or advice on where best to send their members.

Some safe seats weren't "twinned" with nearby marginals.

Overall, critics complained of a lack of coherence.

Then there were the policies.

Individually, some are, by any measure, popular - just as the current leadership claim.

But taken together, one now former MP told me: "It was like the Generation Game conveyor belt. One of the few things we didn't offer voters was a cuddly toy, or if we did, I missed it.

"But all the other items - broadband, pensions, free buses - came so thick and fast no-one could remember them. Not a single voter mentioned a single retail offer on the doorstep."

One phrase unlikely to be used during the "period of reflection" is "Didn't they do well?"

So the big question facing the main, but diminished, party of opposition is this: Does it simply want a new leader, or does it really need a new direction?