Russian domestic violence: Women fight back

Margarita Gracheva

Margarita GrachevaTwo years ago, many Russians were shocked when the parliament significantly reduced penalties for domestic violence. Since then, women have been fighting back - demanding new legislation to restrain abusers, demonstrating in support of three sisters who took the law into their own hands, and finding new ways of tackling outdated attitudes on gender.

On a blustery, grey afternoon, Margarita Gracheva takes her small sons to the playground. They run ahead then jump on to the swings and shoot down the slide. "They're pretty independent for their age," she says. "They know I can't do up their buttons or tie their shoelaces, so they've learned to do it themselves."

On the morning of 11 December 2017 Margarita's husband, Dmitri, offered to give her a lift to work, but instead he drove in the opposite direction, towards the forest. He parked the car, dragged her from her seat, took an axe from the boot and chopped off both her hands.

Then he dumped her in the emergency department of their local hospital in Serpukhov, south of Moscow, before driving to the police station and confessing to his crime.

The couple had met at school and began dating after college. Initially they were happy, though he flared up easily over trivial things - and swore he would kill her if she was ever unfaithful to him.

Margarita Gracheva

Margarita GrachevaTheir relationship soured when Margarita began working in the advertising section of the Serpukhov newspaper. Despite having a degree, Dmitri could only find work driving a forklift truck, and he became resentful of her career and jealous of her male colleagues. At home he was increasingly cold and withdrawn.

When Margarita said she thought they should split up, he ignored her. But when she produced divorce papers he was furious. One night he attacked her in their one-bedroom apartment, waking the children, who saw the bruises on her body. The next time, when he threatened her with a knife, she went to the police.

"I wrote a statement and the desk officer said they would get back to me in 20 days," Margarita says.

"I pointed out that by then he might well have tried to kill me 20 times over."

The desk officer explained that women often made complaints only to withdraw them later, which just swamped the police in paperwork. "So what is the point of getting involved?"

Find out more

- Listen to Russian women fight back, Lucy Ash's Crossing Continents documentary, on BBC Sounds

- Or watch her Our World TV documentary - click for transmission times on the BBC News Channel and on BBC World News

Five days after the case was dropped for lack of evidence, Dmitri cut off Margarita's hands.

Her mutilated left hand was retrieved from the forest and sewn back on in a nine-hour operation. A crowdfunding campaign raised six million roubles (£73,000) for a prosthetic right hand, which was fitted in Germany.

Though Margarita has now published a book about her recovery, called Happy Without Hands, she hadn't wanted publicity to begin with.

Margarita Gracheva

Margarita Gracheva"But the terrible thing is that in order to make sure he got a longer prison sentence, I needed help from the media."

Her lawyers told her that if she didn't get on to national TV, Dmitri would be let out of prison in three-to-five years - it was essential that they felt pressure from public opinion. Margarita took her lawyers' advice, and Dmitri ended up with a 14-year sentence.

Although she is maimed for life, Margarita could easily have suffered a worse fate. Russia doesn't keep statistics on deaths arising from intimate partner violence, but the Interior Ministry says 40% of grave and violent crimes happen inside the family. The most conservative estimates suggest that domestic violence kills hundreds of women a year.

This longstanding domestic violence "crisis", as campaigners call it, helps explain why two developments have sparked protests in cities across Russia. One was the decision taken in 2017 to downgrade domestic violence from a criminal offence to a misdemeanour for first-time offenders, as long as the victim doesn't need hospital treatment. The other was the prospect of long prison sentences being handed down to three sisters arrested for killing their abusive father in July 2018.

The father, Mikhail Khachaturyan - a businessman who made a name for himself running protection rackets in the 1990s - drove his wife from the family home at gunpoint in 2015, then began to focus his aggression on the girls.

"He tortured them at night, wouldn't let them sleep," says the mother, Aurelia Dunduk. "He did whatever he liked. He had a bell and each of them had to come and submit to whatever he desired. The kids were really suffering."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo one night, while Khachaturyan was asleep in an armchair in their home in Altufyevo, a northern suburb of Moscow, his eldest daughter Krestina, aged 19, pepper-sprayed his face. Then 17-year-old Maria stabbed him with a hunting knife while 18-year-old Angelina hit him on the head with a hammer.

"They were protecting themselves - they actually had no choice," their mother tells me.

A public outcry led to them being released from custody while awaiting trial. A petition calling for them to be acquitted has gathered 300,000 signatures.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne of the sisters' supporters is Maria Alyokhina from Pussy Riot, Russia's most famous punk band. When she headlined a fundraiser last summer she spoke about domestic and sexual abuse as "one of the most important problems in Russia" but one that is "always pushed under the carpet".

She added that 80 of the women prisoners she had met during her 18 months in a prison colony (for performing a "punk prayer" in Moscow's main cathedral) were women who had been subjected to domestic abuse "until they just couldn't take it any more".

Few Russian politicians see tackling domestic abuse as a priority. Oksana Pushkina is a rare exception. She was elected in 2016 as a member of President Vladimir Putin's own party, United Russia, but the treatment of women has turned her into a rebel. She is now campaigning to get the 2017 decriminalisation law overturned, and for Russia to pass a specific domestic violence law for the first time.

Getty Images

Getty Images"From the grandstand of parliament, we said you can batter your whole family," she tells me in her office in the State Duma, referring to the decision taken two years ago. "This is a really bad law."

Her list of proposals includes restraining orders to keep abusers away from their victims - which have never existed in Russia - anti-sexual-harassment measures and steps to promote gender equality. But she faces fierce opposition and daily hate mail.

More than 180 Russian Orthodox Church and family groups have addressed an open letter to Vladimir Putin asking him to block her law, arguing that it's the work of "foreign agents" and supporters of "radical feminist ideology".

At a round-table debate in parliament last month, Andrei Kormukhin, a businessman and arch-conservative, warned that the draft law could lead to "the genocide of the family".

Even women are not immune to this way of thinking. Elena Mizulina, a member of the upper house of the Russian parliament, once told Russian TV that domestic violence "is not the main problem in families, unlike rudeness, absence of tenderness and respect, especially on the part of women".

She added: "We women are weak creatures and do not take offence when we are hit."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMizulina seems to have been inspired by a 16th Century literary work called Domostroi, or Domestic Order, a set of guidelines for a happy household edited by a priest who took Ivan the Terrible's confession. The book advocates hitting children "to save their souls" and harsh discipline for wives and daughters. "If women do not fear men or do not do what their husbands or fathers tell them, then whip them with a lash according to their guilt, though do so privately, not in the public eye."

Most Russians would laugh off the idea that they live according to medieval rules, but some recognise that outdated attitudes towards gender are a problem and have been tackling them in ingenious ways.

Elena Kalinina, a young advertising executive, remembers how her own mother told her to put up with everything if she wanted a husband. "We have an expression here, 'If he beats you - he loves you,'" she says. "Twisted logic, yes, but it is still part of our mentality."

She thinks the country's gender imbalance - 79 million women to only 68 million men - diminishes women's bargaining power in relationships.

Earlier this year, she and her team developed a computer game about a fictional couple called Nastya and Kirill, and their toxic relationship.

Project 911

Project 911He shouts at her and calls her a slut for cooking him the wrong kind of dinner. At different stages in the game, players have to choose how Nastya should react. The idea is to put yourself in the shoes of the victim and to see how very few options battered women actually have in today's Russia.

Nastya tries to phone her father for help, and the police who don't take her seriously. The game is based on a real case in which the young woman was killed.

Another innovation created by a young lawyer, Anna Rivina, is a website called No To Violence, which tells victims about their rights and where to go to help.

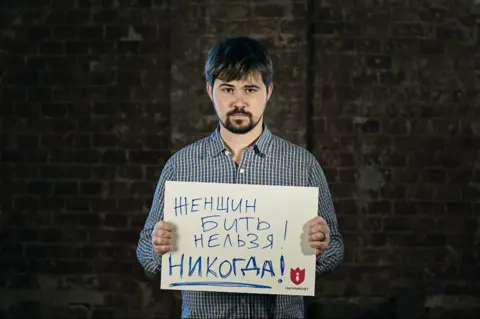

Anna's team of young volunteers use slick social media campaigns to reach women all over the country, including video clips of famous Russian men saying it's uncool to hit women.

Nasiliu.net

Nasiliu.net"We try to work a lot with different celebrities because people are still ashamed to talk about domestic violence," she says.

"When strong successful women say they have suffered from it, it is much easier for others to be honest and that is why we have ambassadors like the actress Irina Gorbacheva, and [the activist and TV personality] Ksenia Sobchak.

"We need practical solutions, but we also need to change attitudes to this problem - we need to speak about it out loud."

Nasiliu.Net has also opened a centre in Moscow providing legal and psychological support. Unlike a state-funded women's refuge that opened in the city five years ago, women don't need to show a passport or residency permit to qualify for help.

All too often, the police seem to be part of the problem.

Margarita Gracheva says that when women write to her asking for advice she doesn't tell them to go to the police, because "they won't help at all".

Mikhail Khachaturyan's wife, Aurelia Dunduk, had an even worse experience. When she reported the beatings she'd received from her husband, soon after her first daughter was born, they immediately called him to the station. Then, when he arrived, they ripped up her statement in front of him. She never bothered going again.

In Solnechnogorsk, an hour north of Moscow, Anna Verba shows me photographs of her daughter, Alyona.

She was a vivacious 28-year-old sales manager and mother of a seven-year-old boy when she was murdered last year by her husband, Sergei Gustyatnikov. On the night of 5 January he waited until their son was asleep, then stabbed his wife 57 times. After that, he left for a dawn shift as a police captain.

"It all happened in this room," Anna says. "Not on this sofa, we had to throw the old one away because it was completely soaked in blood. This wall was splashed in blood."

Alyona's son, Nikita, was the one who discovered the body, when he went into his mother's bedroom the following morning.

"It was only after the official autopsy that I saw the terrible black-and-white photographs," says Anna. "They were bad enough, but what I can't get over is that the child actually saw all this. He told me her eyes were open… He called out to her and thought she blinked."

Wiping the tears from her eyes, Anna says Nikita ran to his own room and sat on the bed with the dog.

"He didn't know what to do - call an ambulance or call the police. In the end he phoned his dad, because he works in the police.

"How cruel do you have to be not only savagely murder your so-called beloved wife, and the mother of your only child, but to also leave that child to find her body?"

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSergei got nine years, a reduced sentence due to the fact that he has an underage dependent and is in the police force.

But Anna argues this should have worked against him, and led to a more serious sentence. "You made your child an orphan and they consider this as grounds for a reduced sentence? It's insane!" she says.

Our conversation is interrupted when Nikita comes into the kitchen to get a snack. He shows us his dog and offers to make us all tea.

When the child returns to his bedroom to play video games Anna talks about her fears for the future. Although Gustyatnikov was convicted of murder, he has not been stripped of his parental rights and could demand custody of the boy on his release.

"Nikita is very afraid of this. He says, 'Where are we going to hide when he comes out of prison? Granny, what are we going to do?'" she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThen she tells me that the summer before the murder, Gustyatnikov took Alyona for a countryside walk, supposedly to make up after a quarrel. On a lonely path, he threw her to the ground and held a knife to her throat. Alyona reported the attack but was later persuaded to withdraw her statement by her husband's colleagues.

"He came and fell on his knees and kissed our feet and asked for forgiveness and said he would never do this again," Anna says.

"He said, 'I really love her, I wouldn't lift a finger against her.' And five months later he killed her.

"I demand as the mother of a murdered girl for there to be changes in the law. I demand that they get rid of the decriminalisation for first-time abusers. There must be punishment.

"Even after my daughter's case, how many more girls have been beaten to death, cut up and strangled? All because the perpetrators go unpunished."

You may also be interested in:

As Russia enters its 20th year under the authoritarian leadership of Vladimir Putin, St Petersburg's vegan anarchist community thrives. Hated by the far right and out of tune with Russia's prevailing nationalist mood, the activists have created a version of what their ideal society would look like - and they're promoting this vision with delicious food.