Four takeaways from this year's GCSE results

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis is a tale of two year groups - those who picked up their A-level results last week and those who have now just opened their GCSE marks.

And the story is very similar in some respects.

Both year groups experienced months of disruption to their schooling during formative years because of Covid, both were afforded special measures for this year's assessments to counteract that disruption, and neither had taken public exams before this summer.

Students receiving their GCSE results on Thursday were part way through Year 9 when the pandemic hit and schools closed during national lockdowns.

Further school closures followed while they were in Year 10, and many pupils also experienced disruption due to Covid at the beginning of Year 11 as well.

That is the context. Here are four key takeaways from this year's GCSE results:

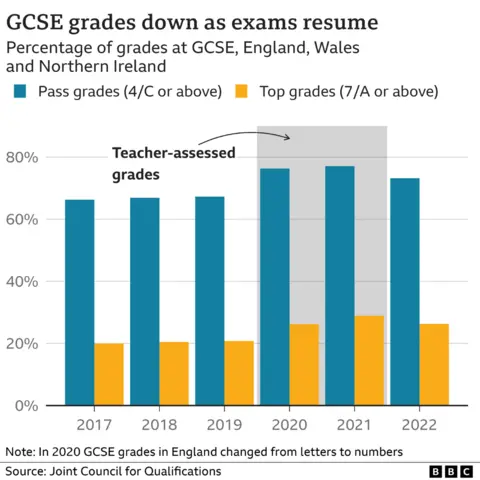

1. Grades have dropped since 2021 - but remain higher than 2019

Across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 73.2% of GCSEs were marked at grades 4/C and above this year - down from 77.1% last year, when grades were decided by teachers.

That percentage is still significantly higher than in 2019, the last year exams were sat before Covid, when it was 67.3%.

The proportion of top grades - 7/As and above - is 26.3%. Again, it is lower than last year (28.9%) but higher than it was in 2019 (20.8%).

The fall since last year is not because this year group is any less capable, it is the result of a system-wide change.

England's exams regulator, Ofqual, has called 2022 a "transition" year, with grades being brought down from the highs of the past two years to be more in line with pre-pandemic results.

But they were still designed to be higher than 2019, out of "fairness" to students in this year group.

The fall in the pass rate this morning matters because in England, where most GCSE students live, they need to pass GCSE maths and English with grade 4 or above in order to move on to further study and do their A-levels or T-levels.

So today's results mean there will be more students who need to resit in England than there have been in the past two years.

These grade 4 passes could also be about to become more important for those in England who want to eventually study at university.

The Department for Education has floated the idea of minimum grade requirements in order to get student loans. Getting at least a grade 4 in English and maths at GCSE (or equivalent) is one option it is considering.

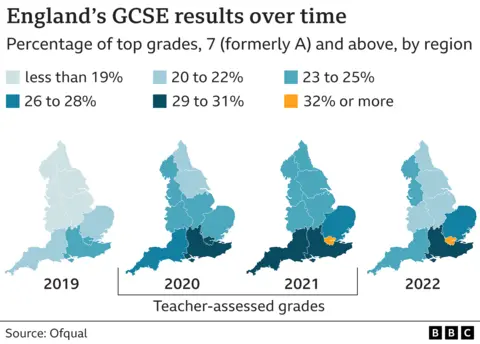

2. The North-South divide grew over the pandemic

There are substantial differences in the percentage of top grades across the country.

In London, 32.6% were marked at grades 7/A and above, compared to just 22.4% in the north-east of England and in Yorkshire and the Humber.

The percentage-point gap here - between the regions with the highest and lowest proportions of top grades - is 0.1 percentage point wider than it was in 2021. But it is 0.9 percentage points wider than it was in 2019.

This educational divide between the North and South existed before Covid but business leaders say it is deepening and have called on the government to give schools more resources and funding.

In a joint open letter, the Northern Powerhouse think tank, Schools North East and the education charity SHINE warn that parts of the country like the North East, that were already behind the South, have been set back further by the "disproportionate learning loss" when schools and classes closed for different periods in the pandemic.

Parts of north England, for example, spent longer stretches under stricter Covid rules under the country's tier system in 2020.

Labour has accused the Conservative government of leaving a "legacy of unequal outcomes that are holding back kids and holding back communities".

The Department for Education in England said it had "set out a range of measures to help level up education" alongside its £5bn Covid catch-up fund, which includes cash for tutoring.

That fund is just a third of what was originally recommended.

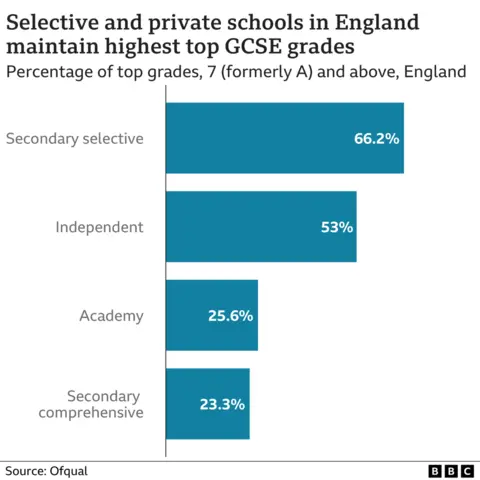

3. The 'disadvantage gap' persists

According to data put out for England, 66.2% of entries from selective schools and 53% of entries from private schools got grades 7/A and above.

That is compared to 23.3% of comprehensive schools and 25.6% of academies.

The gap between private schools and these categories of state-funded schools has narrowed compared to the past two years, but is wider than it was in 2019.

Data published by the Institute for Fiscal Studies last week suggests there has been barely any change in the attainment gap between wealthy and disadvantaged pupils at GCSE level for 20 years.

It also suggests the average gap in per-pupil funding between state and private school pupils rose from £3,100 in 2009-10 to £6,500 in 2020-21.

But the "disadvantage gap" is about more than school spending - especially for students in this year group who did so much home learning.

Family income will have influenced things like access to laptops and the internet, as well as the amount of physical space students had to study.

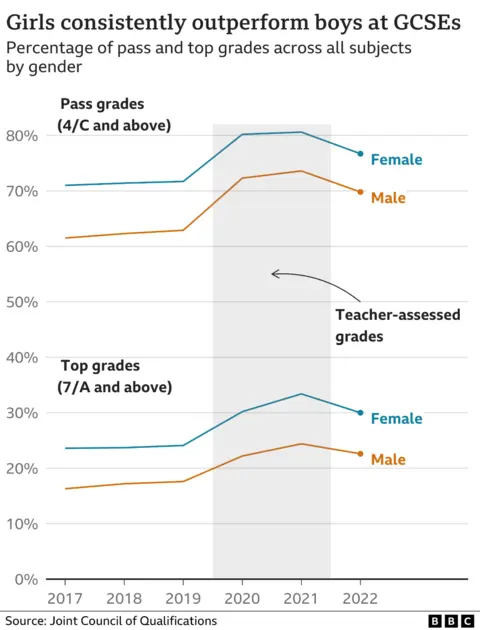

4. Girls continue to outperform boys

Girls have outperformed boys every year since GCSEs were introduced in the late 1980s, and this summer is no different.

30% of girls got the top grades - 7/A and above - compared with 22.6% of boys.

The gender gap in these top grades has narrowed by 1.6 percentage points since last year.

That gap at grades 4/C and above has also narrowed - although very marginally.

Additional reporting by Rob England.