Almost two million pupils regularly missing school

BBC

BBCAlmost 1.8 million children missed at least 10% of school in the autumn term in England, according to new estimates.

The number of children missing at least half of school is also greater than previously thought, at 122,000.

The figures are based on information gathered from 145 councils for the Children's Commissioner.

Dame Rachel de Souza said urgent action was needed to identify the children most at risk, and the reasons why they miss school.

The investigation follows concerns some pupils have never fully returned to lessons after national lockdowns during the Covid pandemic.

It also found no reliable figures for children who never go to school at all, raising the prospects of a small, but vulnerable group of children who are entirely out of sight, and thus impossible for the authorities to keep safe.

Dame Rachel said: "I'm extremely concerned, I'm surprised at the size of it.

"I'm worried about children missing education but also safeguarding and helping those who most need to be back at school to be back."

Unique identifier

She said thought needs to be given about how to make sure children under the age of 18 don't fall through the gaps between school and social services.

"I'm very keen we start to work with a unique identifer for children, that could be the NHS number or one of the other numbers that already exist."

The latest estimates suggest persistent absence from school - missing more than 10% - is at a rate almost twice as high as before the pandemic.

The Department for Education said it had launched a pilot programme to improve the quality of school attendance data.

Blake, who is now 15, started skipping school when he was in year 8.

"I started saying 'I'm going to school' and would just go somewhere else for a few hours. Then when lockdown came I did no work and I got even further behind than I was already.

"I had big gaps in my knowledge and that was dead hard to fill."

Blake lost confidence and found it harder and harder to return to lessons.

His school arranged for him to join a programme for pupils with low attendance at The Hive youth zone in Wirral, where he now has one-to-one tutoring.

As a result Blake will sit some GCSEs this summer and expects to pass Maths and English, allowing him to take up the offer of work and training in a restaurant.

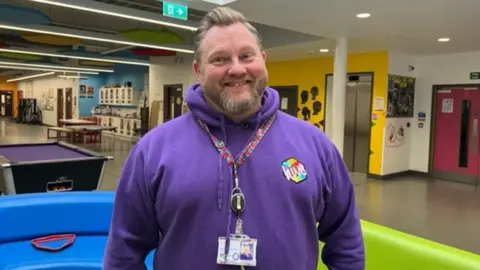

Steve Fogg, who runs the course working with small groups of teenagers, fears more will fall through the gaps in the system coming out of the pandemic.

"It's become much worse, young people got used to not going to school, and if they were having a bad experience before the pandemic, their anxieties rise being forced back into school."

The reasons more teenagers are not attending are varied, but a loss of social and academic confidence is visible after the disruption of recent years.

Even schools that have previously had very good attendance are seeing an increase in persistent absence.

That's the case at St Margaret's Church of England Academy in Liverpool, where Stephen Brierley is the headteacher.

They have a dedicated family liaison officer who gets to know parents or carers and work with them to find out what the barriers are to teenagers returning.

"There are some that have got out of the habit of coming to school, and some have extra social needs so have found it difficult to make that leap to come back to school."

Mr Brierley isn't surprised there are some children who have never been to school at all.

He has dealt with isolated cases of being asked by parents if he can find a place for a teenager who has not received any formal education, in school or through home education.

Such cases are reported to the council because it raises potential concerns about the child's welfare.

"If they are not in school they are at risk of criminal exploitation or being in harms way - it's safer for them to be in school."

In the meantime schools and parents face the challenge of teenagers who have disengaged during the pandemic.

Blake says his experience shows its worth persisting: "If you've tried school and know you can't do it, try to find an alternative.

"You're going to need your GCSEs, and you may as well do them now as later."