More pupils sent home as Covid disruption soars

PA Media

PA MediaThere has been a sharp rise in pupils sent home from school in England because of Covid, according to the latest official figures.

They showed that more than 375,000 pupils - about one in 20 - were out of school for Covid-related reasons, up by more than 130,000 in a week.

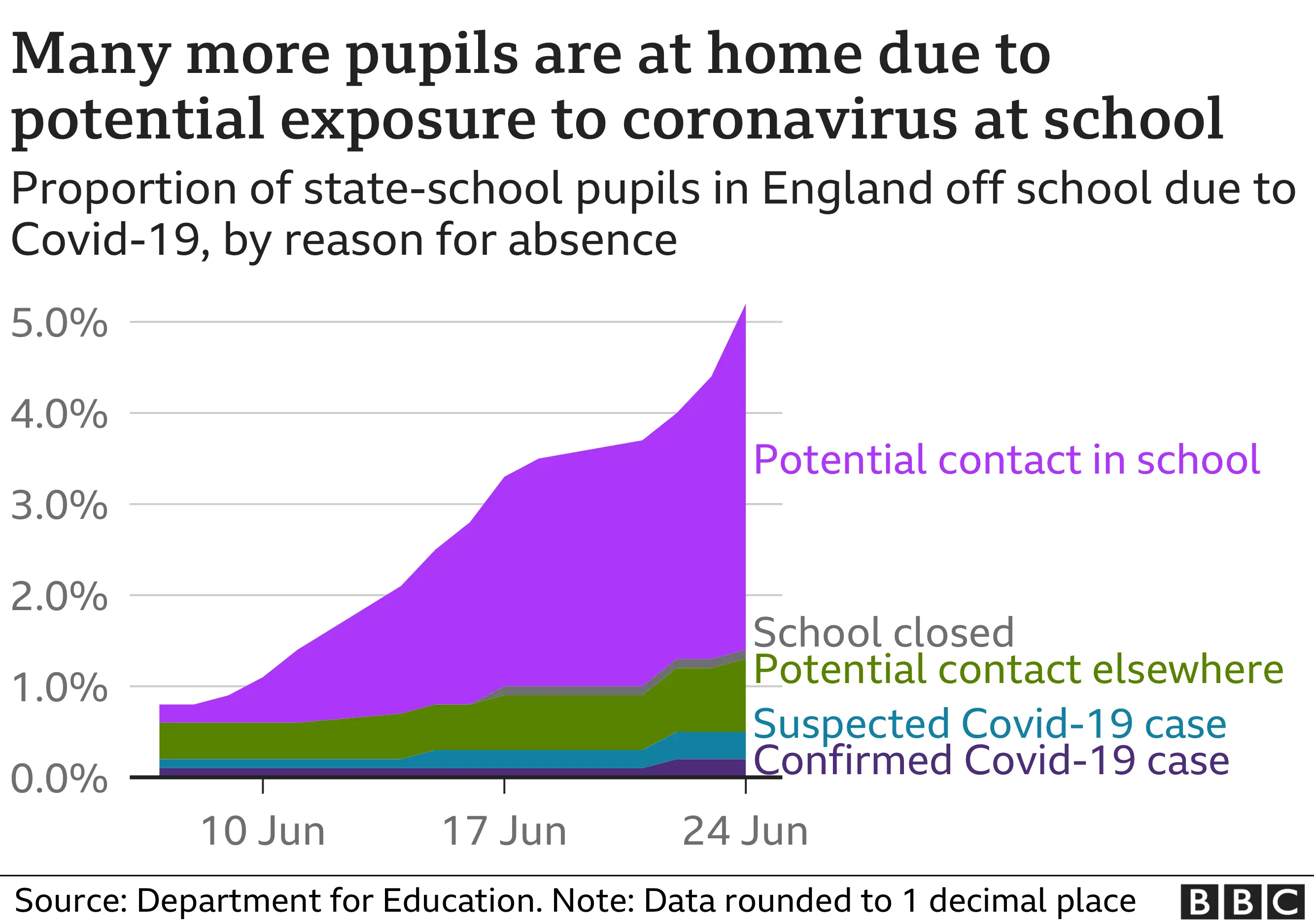

Absences have quadrupled during June.

The government has signalled a shift to more Covid testing for schools in September - rather than having to send home whole "bubbles" of pupils.

The Department for Education figures show the highest number of Covid-related absences since the return to school in March, with 5.1% of children out of school, up from 3.3% the previous week.

- 15,000 pupils at home who are confirmed Covid cases

- 24,000 suspected cases

- 279,000 self-isolating due to potential contact in school

- 57,000 self-isolating due to potential contact in the community

- 5.1% of pupils absent from Covid, up from 1.2% on 10 June

- 13% absent in total, including non-Covid

"The government simply does not appear to have a grip on this situation," said Paul Whiteman of the National Association of Head Teachers - with attendance figures down to levels seen last autumn.

Absences were higher in secondary than primary school in the latest figures, with 6.2% out of secondary school, up from 1.4% earlier this month.

But out of all those young people having to stay at home - only 4% are confirmed Covid cases.

"It is clear that a different approach is needed in the autumn term," said Geoff Barton of the ASCL head teachers' union. But he complained that so far the government's proposals are only "vague aspirations".

More pupils seem to be returning to learning online - with the Oak National Academy, set up during the first lockdown, reporting a big increase in the use of its online lessons, particularly in the north west of England.

Parent's view: 'Feels like there isn't an end to it'

Candice Yates, a parent and physical health co-ordinator at Ellesmere Park High School in Eccles, Greater Manchester, says the increase in self-isolation has been very disruptive for children, families and schools.

"I think psychologically it's awful having to think that you're going to get that call, that your child's going to have to isolate again or they're going to be off again.

"And you just feel like, at the moment, there isn't an end to it all; it's just constantly like losing bits and pieces and chunks of their education.

"Then they're back in, then they're online, then they're back in, then they're off again and it's just hard to watch the kids go through that as well - as a parent and as staff to watch them go through all these different emotions, of one minute being at home, one minute being here.

"Their friendship groups are being affected, not just their education and socially things are being affected for them as well. So it's been tough on them, really tough."

Ms Yates says the situation is also difficult for parents. "I think for families in general it's been quite difficult obviously."

"More than anything, watching other staff members go through it with younger kids (mine are older), but with the staff having to be off if they had a child in nursery, a child in primary and a child in secondary - they were being torn left, right and centre.

"It's been a case of juggling the guilt all the time - if you have to go home to be with your kids, because you've got no other childcare, then you feel guilty for not being in work, if your children are sent home and you're trying to find alternative childcare you feel like you're not there for them because you're at work."

The current approach of whole bubbles of pupils having to self-isolate where there are cases is under scrutiny - and the rules could change in the autumn, in a bid to limit the disruption.

It has been suggested more testing could be used in response to Covid cases - and a pilot scheme in some secondary schools has used daily Covid tests, rather than requiring pupils to self-isolate.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson said he was "working with the health secretary, alongside scientists and public health experts, to relax Covid measures in schools".

"I'll be looking closely at the issues around the need for ongoing isolation of bubbles and the outcomes of the daily contact testing trial, as we consider a new model for keeping children in education," he said.

Labour's shadow education secretary Kate Green said "parents and schools are crying out for help" and called on the government to act before the summer holidays.

Teacher's view: 'Bit of a nightmare really'

"When you've got the majority of the class out and trying to teach them difficult concepts, it's a bit of a nightmare really," says Danielle Stephenson, a science teacher at Ellesmere Park High School in Eccles, Greater Manchester.

In her Year 10 class, Ms Stephenson has 10 out of 14 children currently at home because of Covid cases.

"You're juggling it, trying to anticipate. What things will they need to know when they come back? What am I going to do to catch them up when they get back in? How am I going to make sure I don't make the other kids bored because they've already learnt it?

"So you're trying to catch everyone up to the same speed - it's just really really difficult."

Ms Stephenson says teachers are now always thinking about how they can adapt for children out of school.

But she says there is no substitute for face-to-face learning and has noticed that pupils are much more enthusiastic about being in school now.

"The kids are a lot more happy to see you and I think I actually appreciate them more when I see them face-to-face. So I think the appreciation is on both sides, from the children and the staff."

'Massive national effort'

The government's former catch-up tsar, Sir Kevan Collins, said the "key thing" was to follow the evidence and take advice from experts and scientists on how testing could be used to reduce self-isolation for pupils.

"Ideally, of course, what we all want to do is get every child back in school every day, because that's the very best way we'll recover from the pandemic," Sir Kevan said.

The former education recovery commissioner, who appeared before the Commons Education Select Committee on Tuesday, warned that education inequality could be the "legacy of Covid" and said longer school days could be one way of tackling this.

"I'm personally very, very clear that the biggest impact of Covid will definitely be on our most disadvantaged children."

He confirmed to MPs that he quit his role earlier this month because a £1.4bn catch-up fund, "just wasn't enough to deliver the kind of recovery we need".

"Our country has responded in a way which compared to some others is frankly a bit feeble. This scale of shock requires a massive national effort to recover."