Why did the A-level algorithm say no?

Victoria Jones

Victoria JonesAccusations of unfairness over this year's A-level results in England have focused on an "algorithm" for deciding results of exams cancelled by the pandemic.

This makes it sound Machiavellian and complicated, when perhaps its problems are really being too simplistic.

There have been two key pieces of information used to produce estimated grades: how students have been ranked in ability and how well their school or college has performed in exams in recent years.

So the results were produced by combining the ranking of pupils with the share of grades expected in their school. There were other minor adjustments, but those were the shaping factors.

It meant that at a national level there would be continuity - with this year's estimated results effectively mirroring the positions of recent years.

But it locks in all the advantages and disadvantages - and means that the talented outlier, such as the bright child in the low-achieving school, or the school that is rapidly improving, could be delivered an injustice.

Reuters

ReutersThe independent schools and the high-achieving state schools with strongest track records of exams were always going to collect the winners' medals, because it was an action replay of the last few years' races.

And those in struggling schools were going to see their potential grades capped once again by the underachievement of previous years.

In Scotland the accusations of unfairness prompted a switch to using teachers' predicted grades.

These predictions were collected in England too - but were discounted as being the deciding factor, because they were so generous that it would have meant a huge increase in top grades, up to 38%.

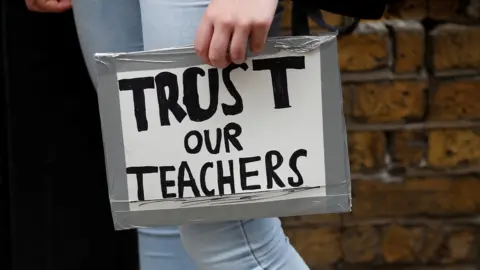

Victoria Jones

Victoria JonesThere were also doubts about the consistency and fairness of predictions and whether the cautious and realistic could have lost out to the ambitiously optimistic.

As a consequence, while teachers might have decided the ranking order of pupils, their predictions have mostly been sidelined.

And the "downgrading" of almost 40% of results has reflected the lowering of teachers' predictions back to the levels that previous history suggests would have been achieved.

PA Media

PA MediaIf these predictions had not been gathered there would not have been any "downgrading" - and perhaps the stories would have been about the overall results being the highest ever - with more top grades than in almost 70 years of A-levels.

Instead there has been uncertainty and distrust.

What has troubled and angered schools has been that while the averages have been protected, individuals could be losing out.

They say the lowering of grades seems sometimes inconsistent and unfair and they are frustrated at the inability to refine what has seemed a clumsy process.

For instance, there was no direct connection between an individual's prior achievement and their predicted grade.

Emma Bowden

Emma BowdenSo if someone got all top grades at GCSE and then moved to a low-performing school for A-level, they might find themselves locked out of getting the grades they might have got if they'd gone to a different high-achieving school.

Schools working hard to make rapid improvements in tough circumstances feel themselves boxed in and that their young people have missed out on opportunities in university.

The problems of social mobility and regional inequalities are not hard to see.

But it's going to be harder to unpick what has happened.

The appeals system could be swamped by angry schools and their pupils wanting to challenge results. Will there be whole-school changes to grades which were decided at a whole-school level?

No one knows yet how appeals over mock exams might work. It was such a last-minute addition that it was announced before the regulator could decide any rules for it.

The "algorithm" also suggests the sense of powerlessness felt by those students disappointed by their results.

It was a "computer says 'no'" way of missing out. Now ministers and exam regulators will have to find a human way back.