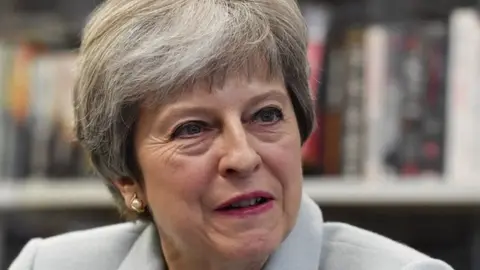

Justine Greening wanted to scrap tuition fees

EPA

EPAJustine Greening says she had plans to scrap tuition fees, before she lost the job of education secretary a year ago.

She says she wanted a graduate contribution scheme to fund England's universities where "you wouldn't have a loan, you wouldn't have tuition fees".

Ms Greening says she was worried that tuition fees of £9,250 per year could start to put off poorer students.

The government said its review of fees would make sure there was "value for money for both students and taxpayers".

'Short-term fix'

Ms Greening, education secretary until last January's reshuffle, says she had concerns that excessively high fees and levels of debt could become a barrier to social mobility.

She says she had been working on a radically different system which would have removed fees - but instead the prime minister launched a review of student finance, chaired by financier Philip Augar.

Ms Greening is scathing about the review, which is expected to report back next month.

Alamy

AlamyShe says its public remit is confused - without any "clear objectives of the problem it was trying to fix".

And she says its private purpose was to buy time and only "tweak" a few of the most politically toxic aspects of the current system.

Even if, as suggested, it lowers tuition fees to £6,500, she says it will still be a temporary sticking plaster.

"What happens if they creep back up to £9,000? Would they re-reduce them again?" says Ms Greening.

"We need a long-term sustainable approach, not a short-term fix that may unravel and then be taken over by the next short-term fix."

Tough questions

Ms Greening, hailed as the first Conservative education secretary to have attended a comprehensive school, said she realised there had to be a different approach after hearing what students were saying about fees during the 2017 general election.

It was a campaign in which Labour promised to scrap fees entirely and the Conservatives saw big swings against them in university seats.

"There was a real desire within the DfE to take a fresh look at some of these issues - and to challenge ourselves with being ahead of the curve, even if the rest of government had little interest in broader reform," she said.

"I felt that we should be looking and asking ourselves some tough questions - about what it might look like."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the months before her departure from office, she said the "basic architecture" of an alternative funding system was worked up.

The proposal was for a system without fees, loans, debts or interest rates.

Instead, graduates would pay back a proportion of earnings over a fixed number of years, with this graduate contribution funding universities.

She likens it to a time-limited form of National Insurance deductions, but only for graduates.

High debt

It would remove negative perceptions over high fees and £50,000 average debts on graduation - and would prevent a cap on the number of places.

Ms Greening says poorer students had so far not been significantly deterred by fees, but it was "getting to the point where it felt that they were too high".

She argues her graduate contribution proposals would be more progressive - as higher earners would pay more.

Reuters

Reuters"There could be someone going off into the City and paying off their loan and avoiding all the interest with one bonus cheque - compared to a nurse," she says, who could be paying it off for 30 years.

The graduate contribution would keep the principle of students paying towards higher education.

"Most students recognise they should make a contribution, because they're getting an opportunity," she says.

But it would mean ditching the idea of a higher education marketplace in fees, which was at the heart of the reforms that created the tuition fee system.

"You have to confront the fact - did universities compete on price? No," she says.

Party political failures

But her plans for such a massive change went nowhere.

"We were working up this proposal before the reshuffle," she says.

"Of course, it had tons of work to be done, all sorts to refine and understand the trade-offs," but she believed it to be a "more sensible approach".

Instead she was replaced as education secretary and a review of student finance was announced.

She has since set up the "Social Mobility Pledge", working to improve opportunities in the workplace, and is on the front lines of arguments over Brexit - supporting calls for a second referendum.

Looking at policy over tuition fees, she says the divisions over Brexit show how ineffective the party political system has become at reaching long-term decisions.

"I don't think Britain or British politics will ever be the same again.

"I think it's a sea change. It's a call to action to genuinely create a different country to tackle some of the problems that sat behind a lot of the Brexit vote.

"And I think for British politics, we've got to ask ourselves some difficult questions about why party politics seemingly cannot rise to the challenge of delivering on long-term problems."

A Department for Education spokesman said: "Students rightly expect value for money from their degree, which is why the government is conducting a major review of post-18 education and funding - to ensure we have a system that is joined up, accessible to all and provides value for money for both students and taxpayers.

"Work on the review is still ongoing, and more information will be available in due course."