Could student loans ruling mean the system is redesigned?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn announcement on Monday could affect the future of the student loans system.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) will be announcing the outcome of its review of how student loans are treated in the national accounts.

That sounds like pretty technical stuff, but it could be significant.

At the moment, students in England are lent money to cover their tuition fees and living costs. Interest starts being added straight away. When they start working, the graduates pay 9% of their income above £25,000 until the loan plus interest has been paid off. Any outstanding debt left after 30 years is written off.

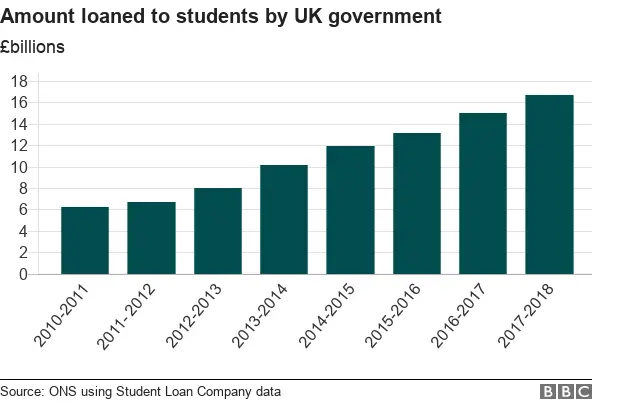

The money that the government has been lending has been going up. This year it's expected to lend £17bn and receive repayments of £3bn.

The total outstanding student loans at the moment have reached more than £100bn. That's expected to rise to £1tn in cash terms by the mid-2040s and £1.5tn by the late 2050s.

Clearly, these are very large sums of money, and the ONS is going to rule on how that money should be treated on the government's balance sheet.

Every year at the start of the Budget you will hear the chancellor announcing the forecasts of what will happen to the deficit and the debt in the coming years.

Remember, the deficit is the amount borrowed in a single year - the debt is the total amount owed on money borrowed by successive governments.

The way the national accounts currently treat student loans is "genuinely bizarre", according to Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

He explains that when the government lends students £14bn this year (that's £17bn in loans minus £3bn in repayments), government debt increases by £14bn, but the deficit is unaffected.

And, if counted, it would make a big difference to the deficit - last year's deficit was £40bn, so £14bn is a significant amount.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe reason that the money goes on the debt and not the deficit is that it is treated as a loan that will all be paid back one day.

That means the only time it would affect the deficit is in 30 years, which is when any unpaid loans and interest are written off - well outside the time horizon generally targeted by governments.

This is strange because nobody expects all of the money in student loans to be repaid - the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that only 38% of the money and interest will be repaid.

Another odd thing about it is that, every year, the amount of interest added to the loans counts as money the government has earned, even though most of it will never be paid.

Now the ONS is going to decide whether to change the system after the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee described it as a "fiscal illusion" that concealed the real public cost of tuition fees, and the Treasury Select Committee said the system had meant higher education spending "escapes scrutiny".

Grants not loans

The OBR looked at options for the treatment of student loans and decided that two of them would make sense:

- All money loaned to students is treated as a grant not a loan (so no assumption of repayment) while all money repaid by graduates is treated like tax receipts.

- Treat the proportion of the loans that the ONS expects to be repaid as loans and treat the rest of it as grants. Only count the interest charged on the loans as government income.

Both of these methods mean that more of money loaned to students affects the deficit when it is lent, rather than in 30 years.

The government has commissioned a review of the student loans system led by Philip Augar, which will not be reporting until after the ONS has taken its decision.

Reclassifying some of the loans as grants "may shift the balance of funding from fees and maintenance loans back towards grants", according to David Robinson from the Education Policy Institute.

"It's also likely to encourage the government to limit increases in student numbers to avoid further damage to its balance sheet."

On the other hand, the government could reasonably say that its fiscal targets should still be judged excluding student loans, because the goalposts have been moved. It could even change the law, as it did with housing associations, to encourage the ONS to change its mind.

But Martin Wheatcroft, an adviser to the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) told Reality Check: "A change would probably affect the way the Treasury sees student loans, perhaps causing it to impose more constraints on how much universities can charge in fees and how many students are eligible for loans."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe current treatment also gives the government what the OBR calls "a perverse incentive" to package the loans and sell them to private investors, who pay up front for the right to benefit from future repayments.

When in December 2017 the government sold £3.5bn of student loans for £1.7bn, the only impact in the public finances was that debt was reduced by £1.7bn.

Remember that these were loans that the accounting system assumed were going to be paid off in full. But there was no recognition of the gap between the face value and the sale price.

Although the ONS is not reviewing the way it treats the sale of the student loan book, making the national accounts treatment of the loans more realistic would be likely to make the sales less attractive.

HM Treasury told Reality Check that it would not comment on the review until it has been published, but pointed to the National Audit Office's review of the sale of loans last year.

The NAO said the sale had achieved value for money, although there was considerable uncertainty about the value of the loans.