'Should I stay or should I go now?'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEmilia Wilton-Godberfforde is facing a big decision - will she continue working as an academic in UK universities after Brexit?

She is British but her husband is French and they are worried about the uncertainty of their future status and what she calls rising "xenophobia".

They also fear a loss of EU research funding will threaten university jobs.

The universities minister says UK access to EU research budgets will "remain unchanged" until at least 2020.

There are about 36,000 academics from European Union countries working in UK universities - and there are others such as Ms Wilton-Godberfforde who have family links to European researchers and academics.

'Wait and see'

EU nationals are about 17% of the UK's academics - and since the referendum there have been brain drain warnings from universities.

Margaret Gardner, vice-chancellor of Monash University, in Australia, recently said Australian universities were already poaching academics from the UK.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut so far the evidence doesn't show an academic stampede. Instead, it suggests a picture of "wait and see".

"We're nervous. Nothing is made clear about our status. It's promises and half-promises," says Ms Wilton-Godberfforde, who has been a research fellow at the University of Cambridge and is teaching French language and literature for the Open University.

Her husband is a French, Cambridge-educated scientist and they have a young child - and the family is struggling with a sense that Brexit has made them feel "unwelcome".

"It doesn't feel like home," she says.

It's a conversation she says is running through universities - with European staff choosing whether to put down roots or to move away.

Research promise

If Ms Wilton-Godberfforde and her husband choose to stay in the UK, she doesn't know what type of bureaucracy and uncertainty will surround their new status.

And she is "massively upset" at the sense that things are going backwards for her generation - and that barriers are being put up to her mobility.

"It feels like everything is shrinking, we're penalised for looking outwards," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy contrast, Cambridge professor Robert Tombs is pro-Brexit and rejects the link between leaving the EU and xenophobia.

"Britain is not a xenophobic country," he says in a podcast for a group putting the views of pro-Brexit academics.

"Race relations are much better than in most European countries which are solidly in support of the EU.

"There's no simple co-relation between disliking foreigners and not liking the EU."

There are, however, also job worries over Brexit and EU research funding.

And Dr Wilton-Godberfforde says she worries about academics "grappling for grants that no longer exist".

The Universities Minister, Sam Gyimah this week gave assurances that UK universities would have the full benefits of the current research round, even though it stretches beyond the UK's departure date from the EU.

Even if there was no deal, the UK government had promised to underwrite any commitments, he said, answering an MP's question.

"This guarantees funding for UK participants in projects ongoing at the point of exit," said Mr Gyimah.

The 100bn euro question

But there is even more EU research money at stake from 2021 - about 100bn euros in the next round - and so far not much clarity about the UK's access to this.

The UK's universities, highly rated by international standards, have been among the biggest winners of EU funding, net beneficiaries by about 3.4bn euros in the most recent round.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd they would have hoped to get a big slice of the next pot of research cash, but that is now uncertain.

It's possible for non-EU countries to participate by paying for associate status. But that would also mean a loss of voting rights and giving up control over how the money is allocated.

Universities UK are so far optimistic - saying that it's mutually advantageous for the EU to have access to top UK university researchers.

But Ludovic Highman, at the Centre for Global Higher Education, at University College London, warns that it is "not a given".

The decision will depend on the final Brexit negotiations.

Will EU students stop coming to UK universities?

There are about 135,000 EU students in UK universities - and their future status is more "wait and see".

It depends on a reciprocal deal over the status of EU students in UK universities and UK students in the EU.

This will determine whether UK students can carry on not paying tuition fees in Holland and whether EU students will continue to head for the sought-after universities in the UK.

If, on the other hand, they become fully fledged "overseas" students, it will mean much higher fees.

EU students are highest in number in Russell Group universities, in London - and, with the lack of tuition fees, in Scotland.

Top 10 UK universities with the highest proportion of EU students

- University of Aberdeen

- London School of Economics

- Imperial College London

- Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh

- School of Oriental and African Studies, London

- University of the Arts, London

- University of Cambridge

- University of Essex

- King's College London

- Edinburgh Napier and University College London

In overall numbers, UCL has the most EU students, almost 4,500. But the highest proportion, over 19%, is at the University of Aberdeen.

On short-term exchanges, such as under the Erasmus scheme, it seems increasingly likely that the UK will continue to participate, paying to have associate status.

Is this France in London or London in France?

There has been a spate of announcements of close partnerships between UK universities and European counterparts.

But Imperial College London has gone a step further.

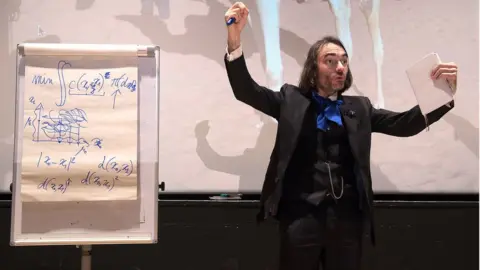

Fergus Burnett

Fergus BurnettThe leading science institution has an arrangement with a French government research body that will give UK academics access to EU funding after Brexit.

The Unite Mixte Internationale (UMI) Abraham de Moivre has been created as a maths laboratory in London, in partnership with France's National Centre for Scientific Research.

This is the first time that the French government has co-funded such a research unit in the UK - and from the French perspective, this new centre in London will have the same status as a laboratory in France.

For Imperial, it means staff at the new maths research unit will have equal access to funding, regardless of their nationality.