'Pinball kids experience too much change in care'

Children's Commissioner's office

Children's Commissioner's officeThousands of "pinball kids" are being moved around the care system with too much instability, the children's commissioner for England has said.

Anne Longfield says nearly 2,400 children changed home, school and social worker during the 2016-17 year, while 9,060 had two of those changes.

Ms Longfield says instability puts them at greater risk of gang membership, grooming and exclusion from school.

The government says it has taken a range of measures to address the issue.

The children's commissioner's stability index report, now in its second year, compiles data on children moving around the care system in England, with a view to improving outcomes for young people.

What are the findings?

The report says stability is crucial for the 70,000 children currently in the care of local authorities in England, saying instability can compound "the difficulties they have already had to endure".

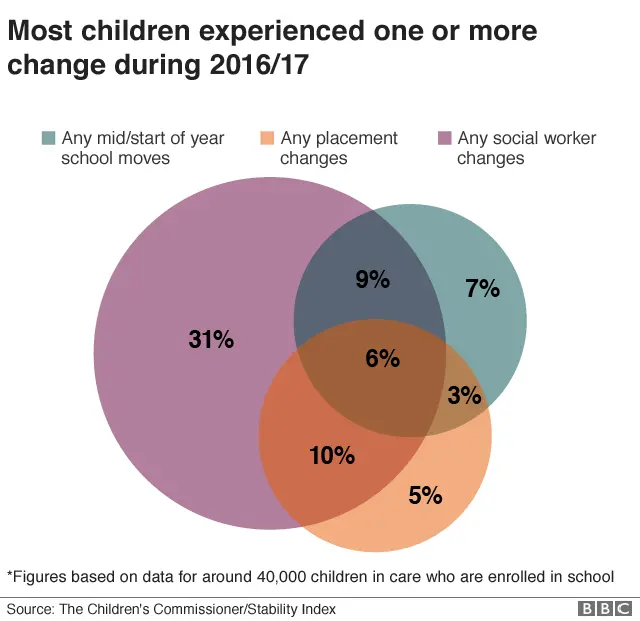

It says: "We estimate that the majority of looked-after children - 74% - experienced some form of change during 2016-17: a placement move, a school move or change of worker.

"This is equivalent to 53,500 children."

It also warns that 10% of children in care attending school - 4,300 young people - experienced a school move mid-way through the academic year, "over twice the rate of mid-year school moves amongst the full school population (4%)".

The report says older children - especially those entering care from the age of 12 to 15 - are most at risk of instability and may need extra support to prevent placements breaking down.

What does this mean for the young people themselves?

Young people who are either in care, or who have experienced being in care, told the BBC News website that instability can have a detrimental effect on their well-being.

Ethan, 14, - whose full name we have not used - has had one emergency placement, two foster family placements and four social workers over the past four years.

But he has now had three happy years at his care home and says he has benefitted hugely from the stability it has given him - he has been predicted to gain good GCSE grades and is hoping to go on to boarding college.

"Being in a stable place, I'm being managed, the people around me are in control and are helping me to move on.

"It's calm, it's relaxed and I think that's a contributory factor to where I am now, my well-being, my emotional stability."

Antony Corrigan, 34, experienced a lot of change as a child in care - he went to four primary and four secondary schools.

"You find it difficult to make a friendship group and you become alienated," he says.

"I had at least 10 placements, including two children's homes and in terms of social workers, I lost count, but I probably had about 10 in total.

"I just wish there was more consistency in the care I was given. It's so easy to get lost in the system, no-one's pushing you or encouraging you."

Ethan agrees, saying children in care who have too many many changes to deal with can't focus on building their futures.

"It would be a struggle for them because they'd be worrying about what's happening, who they're going to going to be with.

Twitter

Twitter"All their focus is on that worry, rather than focusing on their well-being and how they can improve and build a sustainable future for themselves."

Care-leaver Liam, now 22 and studying for a degree, was fortunate not to have too much disruption when he was in the care system, but he says he knows a lot of others who have moved around.

"Psychologically it can be quite damaging because you think nobody really wants you and you're pulled from pillar to post, not being wanted.

"People say you always have a safety net of friends and family, but when you're in care, generally you don't have that safety net," added Liam, whose full name we have not used.

"As a child you need security and to know that someone's going to look out for you."

What does the children's commissioner say?

Ms Longfield says: "Every day I hear from 'pinball kids' who are being pinged around the care system when all they really want is to be settled and to get on with normal life.

"These children need stability, yet far too many are living unstable lives, in particular children entering care in their early teens.

"This puts them at greater risk of falling through the gaps in the schools system and opens them up to exploitation by gangs or to abuse.

"The care system does work for many thousands of children but our ambition should be for every child growing up in care to have the same chances to live happy, healthy and rewarding lives as any other child.

"We put that at risk if we are expecting some children to constantly change school and home."

How has the Department for Education responded?

Children and Families Minister Nadhim Zahawi said: "Children in care are some of the most vulnerable in society and it is important that we provide them with stability and support so they have the same opportunities as any other young person.

"We have taken a range of measures to help create a stable environment including the creation of a virtual network of head teachers to help looked-after children at school, giving those children priority in the school admissions system and funding new projects through our children's social care innovation programme to increase support."

What do other groups say?

Richard Watts, chairman of the Local Government Association's Children and Young People Board, said councils were supporting record numbers of children and young people through the care system.

"Ninety children a day entered care in the last year, and councils saw the biggest annual increase of children in care since 2010," he said.

"This is against a backdrop of unprecedented cuts to local authority budgets, with children's services alone facing a funding gap of around £2bn by 2020."

Mr Watts said while the LGA would share the report findings with councils, the government had "a role to play, in supporting councils to provide the best possible experience for children in care".

Graham Baker, chief executive of Outcomes First Group, said: "A significant proportion of looked-after children have been subject to childhood trauma, emotional hardship, multiple placements and subsequent lack of support from social groups - issues that typically lead to truancy, gaps in attainment and a shortfall in elementary foundation skills.

"Understanding where they have come from, where they are currently and close liaison with relevant therapeutic teams is essential."

Natasha Finlayson, chief executive of Become, said: "There is far too much complacency.

"Tackling these sorts of inequalities is vital if we are to narrow the gap in educational - and therefore employability - outcomes between children in care and their peers."