Teaching boys that 'real men' would stop rape

Alex McBride.

Alex McBride.Isaac, a 15-year-old boy, watched as a group of men grabbed a young girl. It was a bustling new year's eve in Kibera, Kenya's largest slum, and he knew she was in trouble.

He also knew he didn't have the strength to fight off those older, larger men. Having been taught to intervene if he sees predatory behaviour, Isaac called over another man to help confront the group.

"Everyone started arguing," explains Isaac. "The group said the girl was their 'catch' and they had to rape her."

After 20 minutes, they decided to let her go.

"The stories you hear are shocking," says Anthony Njangiru, a field co-ordinator for the Kenyan non-profit Ujamaa, which trains boys like Isaac to help stop violence against women and girls in the slums of the capital, Nairobi.

"Not everyone is so lucky," he says.

Changing attitudes

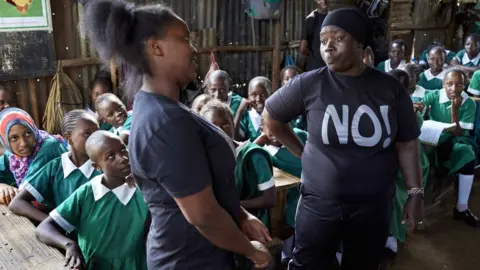

Mr Njangiru teaches a programme called Your Moment of Truth to boys, aged 14 to 18, in secondary school.

He is one of many instructors, and the classes cover everything from sex education, to challenging rape myths, consent, and how to intervene if the boys witness an assault taking place.

Alex McBride

Alex McBrideFor younger boys, aged 10 to 13, a programme called Sources of Strength focuses primarily on body changes.

The course takes place over weekly two-hour lessons, for six weeks, and each class is divided into two, with girls taught their own set of skills.

Since the organisation first began, Ujamaa has taught 250,000 children in over 300 schools across Nairobi.

When it comes to the boys, it's ultimately about changing their perceptions and attitudes towards girls.

"If we, as boys and men, are part of the problem, then we can be part of the solution," says Mr Njangiru. "We can be the first people to change."

Confident 'no'

The programme has been working to stop boys thinking that if a girl said "no" to sex what she actually meant was "yes". Or that it was justifiable to rape a girl if she wore a short skirt.

"They tend to use the girl's weakness to their own advantage," says Mr Njangiru. "If she says no, but she doesn't confidently say no, for them it's a 'go zone' - they just do whatever they want."

The results are impressive, according to research from Stanford University in the US.

Alex McBride

Alex McBrideFollowing the Your Moment of Truth classes, the percentage of boys who intervened when they witnessed a physical and sexual assault rose from 26% to 74%.

Boys were also found to be less likely to endorse myths about sexual assault and the incidence of rape by boyfriends and friends had fallen.

Among female participants in the project, there was a remarkable 51% decrease in the reported incidence of rape.

Violence against women

Sexual harassment has become a worldwide issue and these programmes in Kenya, teaching young people how to recognise and prevent sexual violence, seem to be working.

Violence against women is a huge problem in Kenya.

This worsens once you enter Nairobi's slums, where research has suggested that almost a quarter of girls will have been victims of sexual assault in the previous year.

More from Global education

- 'Don't arm our teachers' say survivors of Florida school shooting

- The billions in 'invisible aid' sent back home by migrant workers

- No access to school? The lessons that come by boat, taxi and truck

- 'Counting every school shooting so it never seems normal'

- 'Guns and survivalists, but no school until I was 17'

- Is falling asleep the most creative thing you do all day?

- Preventing child brides: 'I was 12 when I married a 35-year-old'

- US and England pull schools out of Pisa tests on tolerance

The editor of Global education is [email protected]

The Ujamaa course was designed under the No Means No Worldwide programme, an initiative to reduce sexual violence in Kenya's capital.

In 2010, they started teaching Nairobi schoolgirls how say "no", how to identify risk and talk their way out of trouble.

If that "no" is ignored, they also learn physical skills - how to target weak spots such as eyes, groin and knees - to fight off attackers.

Standing up

But research suggested that much of the problem was from boyfriends and friends.

So Ujamaa extended its programme to include boys, because as Mr Njangiru says, the ingrained attitudes of boys contribute to sexual violence.

Alex McBride

Alex McBride"In African society, men have been brought up with the belief that women have nothing to say, that men are the priority," he explains. "So we try first to change that mentality."

The organisation encourages boys to feel "courageous" enough to stop any assault from happening. To do this, they teach approaches that range from walking away from a classmate who is bad-mouthing a girl to shouting at a potential perpetrator.

"We want the boys to be confident enough to stand up for what they believe in," explains Mr Njangiru.

"But we always remind them of their safety. They shouldn't be getting hurt if they're intervening in a situation. If their life is at risk, they should alert their companions or involve the authorities."

Throwing stones

Many boys talk about using the training in real-life scenarios.

An 11-year-old schoolboy said he saw a man appearing to be about to sexually assault a baby.

To help, he shouted, threw stones in his direction, and tried to grab the attention of others milling nearby.

Alex McBride

Alex McBrideWhen the man realised he was being watched, he zipped himself back up and ran off.

Isaac explains that the Your Moment of Truth training had helped the boy to intervene. "And it's given me the courage to decide to tell you this today."

While the focus is on stopping violence against girls, it also raises the question of sexual violence against boys.

"When we started, the boys were silent, they never used to speak about their problems," explains Jacqueline Mwaniki, another Ujamaa field co-ordinator.

"But after the training, we find that they approach the male instructors and say: 'Hey, I have a problem, can you help?' They're much more able to speak up."

'Do the right thing'

The Kenyan programme has been so successful it is being rolled out in Malawi and there are plans for a launch in Uganda.

At the end of each class, the teachers do a "shout out" to ensure everyone leaves on a high.

In St Joel's secondary school, in north-eastern Nairobi, 30 girls fill the dusty classroom with their powerful voices: "Get back, I'm not intimidated!"

Repeating the teacher's mantra in unison, they chant: "I said no, don't touch me!"

Just across the courtyard, the boys are doing the same. Dressed in white shirts and teal-coloured shorts, they shout and punch the air.

This time, however, it's a slightly different message. "Life will test me," they yell. "I have to be ready to do the right thing."

This story is part of a European Journalism Centre project about men engaging in campaigns for women's rights.