Poorest areas face biggest cuts to children's services

santypan

santypanMary, not her real name, knows all about the consequences of family breakdown.

She has taken a relative's two children into her home in Birmingham and believes that with earlier intervention from social services they would still be living with their mother.

But, she says, social workers took action only once the family had reached crisis point.

Earlier help, perhaps in the form of parenting classes or counselling for the children's mother or even budgeting and cooking classes of the sort available in many council-run children's centres would have made a big difference, she says.

"It would have made a lot of difference. It maybe would have helped probably keep the family together and not have it broken up the way that it is," she says.

Amid warnings from councils and charities that a spending squeeze is threatening early help for vulnerable families in England, new figures seen exclusively by the BBC lay bare the scale of the problem.

The analysis of Department for Education figures by researchers at Huddersfield and Sheffield universities shows that since 2010, council areas with the highest levels of deprivation and need have faced the biggest cuts.

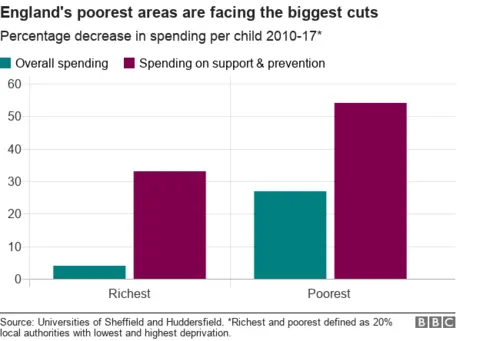

Adjusted for inflation, the figures show overall spending on children's services has fallen by 16% across England - but in the poorest areas the figure is 27%, compared with 4% in the wealthiest areas.

And spending on intervention services to help families before they reach a crisis has fallen by 47% overall - but the figure in the poorest boroughs is 54%, while in the wealthiest it is 33%.

BBC News

BBC News A Department for Education spokeswoman said the government had committed £20m to provide "additional support to local authorities where the risk of service failure is highest".

"In addition, more than £200bn has been made available to councils for local services, including children's services, up to 2019-20.

"We want every child, no matter where they live, to receive the same high quality care and support," said the spokeswoman.

But Prof Paul Bywaters of Huddersfield University, who led the research, said the scale of the budget crisis councils faced meant they were being driven towards short-term cuts that could cost more in the long term.

"It's not only that children are suffering now, but we're storing up costs for society in the future and creating a kind of vicious spiral," he said.

"The more we cut prevention and family support services and concentrate expenditure on the other areas, the more likely it is that more children will come into care, more children will be at risk of abuse and neglect."

Birmingham's Adderley Children's Centre, in Saltley, used to provide specialist early support for families in difficulty - but budget problems meant this ended just before Christmas.

Deputy head Nicky Hinchliff says the community has lost a place where parents and children could feel safe, with expertise on site to offer early support to mothers with difficulties ranging from debt to depression and stop problems escalating.

"Those issues have not gone away," she says.

"Those parents and those families still need our support.

"I dread to think what that means for children in the longer term."

On the other side of Birmingham, in Winson Green, Mary gets some support at a charity-run centre at a primary school.

At the Oasis Hub, parents can drop in to learn cooking and budgeting skills from volunteers.

Many parents here are under pressure, with money or other worries, but in these sessions, they can find counselling, childcare and friends.

"It builds their confidence. It builds their skills. And obviously having the mothers emotionally stable, helps the children, and happy parents means happy children," says one volunteer.

Centre manager Anji Barker says staff have noticed that neglect cases are on the rise.

"What we see is that where that early help could have happened, and then mum was able to get on her feet and keep those children and then go on to actually be a very effective parent, we are now seeing that's just left and left and left until the crisis emerges," she says.

"And then you are at the very top end of crisis that involves removal of children."

'Difficult choices'

Birmingham City Council's deputy leader, Brigid Jones, said the council had been required by the government to make cuts of more than £642m since 2010.

"Faced with incredibly difficult choices, we chose to protect and increase funding to our child-protection service. And sadly this has inevitably meant cuts for other services across the council, even those we would normally consider vital, like children's centres."

The Local Government Association, which represents councils in England, said it had repeatedly warned of a £2bn funding gap in children's services by 2020.

"It is often those who are most vulnerable and need support across a wide range of services to improve life chances who rely on these services the most," said Richard Watts, who chairs the LGA's Children and Young People Board.

Additional reporting by Sophie Woodcock and Judith Burns