Who really goes to a food bank?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFood banks are an intensely divisive image, an uncomfortable underbelly of austerity often in touching distance of conspicuous wealth.

They seem hard to explain - and Theresa May stumbled awkwardly when asked about them during the election campaign, getting no further than saying they were used by people for "complex reasons".

But what are the reasons? And who are the people depending on food handouts? Are they struggling families in need of help? Or are food banks magnets for scroungers? Are they mostly being used by local people or by migrants?

A major study from researchers at Oxford University and King's College London has tried to get beyond the stereotypes, looking at those using the Trussell Trust's network of food banks.

In the most basic terms, these are people with many overlapping forms of "destitution".

They have been missing meals, often for days at a time, going without heating and electricity. One in five had slept rough in recent months.

They are at the lowest end of the low-income spectrum, with an average income below £320 per month, described as living in "extreme financial vulnerability".

These are usually people of working age, middle-aged rather than young or old, mostly living in rented accommodation.

About five out of six are without a job and depending on benefits.

Insecure work

But among those in employment, this is usually unpredictable, insecure work, with an unreliable income.

The long stagnation in wages seems to have made it harder to be self-reliant through work - and the research warns of the rising number of jobs that are low-paid and insecure.

The best inoculation against needing a food bank seems to be a full-time permanent job.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough there have been reports of people in regular jobs turning to food banks, the research suggests this remains very unusual.

But there are some distinct characteristics of food bank users that are different from the general face of poverty.

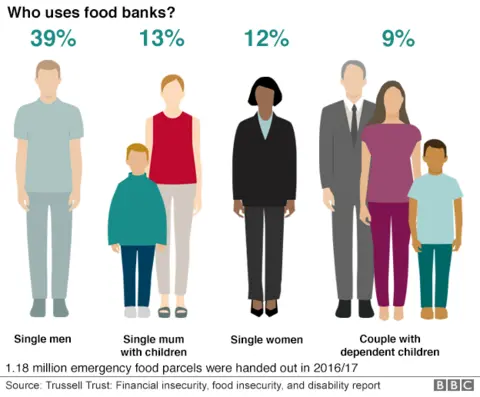

The most typical users are single men, lone mothers with children and single women - between them accounting for about two-thirds of all food bank users.

Social isolation, the lack of a friend in need, plays a part, as well as threadbare finances.

Ill health is a very common feature. Almost two-thirds of users had a health condition, half of households using food banks included someone with a disability and a third had mental health problems.

Debts and a long tail of repayments are often dragging them down.

They can be months behind with bills and having to pay back bank loans, credit cards, loan sharks, pawn shops and payday lenders.

Income 'shocks'

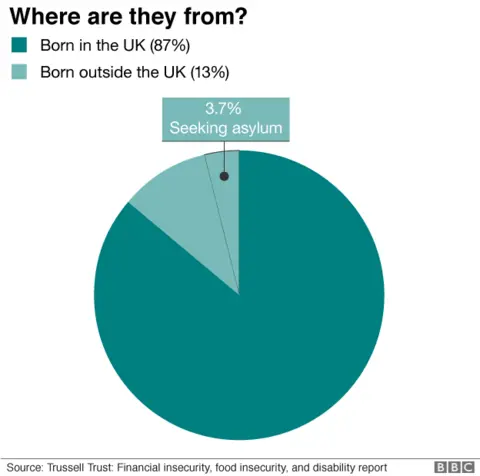

Food bank users are overwhelmingly UK born and even though 4% have a university degree, they have much lower education levels than the average working-age population.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPut together, it shows people living closest to the edge being the first to be pushed over. Lone adults, saddled with debts, with ill health, high levels of depression and anxiety and few qualifications to get a more secure job.

These are people on the margins in many ways.

But the researchers show that living on "chronic low incomes" and facing "severe food insecurity" are not necessarily the tipping points.

There is often something else - an income or expenditure "shock" - that puts them on the road to the food bank. This can be a rise in rent, energy bills or the cost of food; or it could a delay in benefits or fewer working hours.

On wafer-thin margins, it can be enough to literally turn out the lights and leave nothing for food.

The research is also a reminder that the prevalence of food banks is a recent phenomenon, a tale of our times. In 2010-11, the Trussell Trust gave out 61,500 food parcels, but by 2016-17 this had risen to almost 1.2 million.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRachel Loopstra, lead author of the report and lecturer in nutrition at King's College London, said people had been "surprised and shocked" at the growth in food banks.

But there had not been enough understanding of the circumstances that meant people ended up having to ask for food.

Dr Loopstra said the study showed how apparently small changes in income or outgoings could leave people with absolutely nothing, even for the most basic of needs.

Over two-thirds of food bank users had often been going without food.

"The severity of food insecurity and other forms of destitution we observed amongst people using food banks are serious public health concerns," she said.