Work near home: The co-working hubs for locals

Benoît Grogan-Avignon

Benoît Grogan-AvignonThe billion-dollar business WeWork has filed for bankruptcy in the US, but that doesn't necessarily mean co-working spaces are going out of fashion. The concept may simply be evolving - to the benefit of High Streets in towns and suburbs.

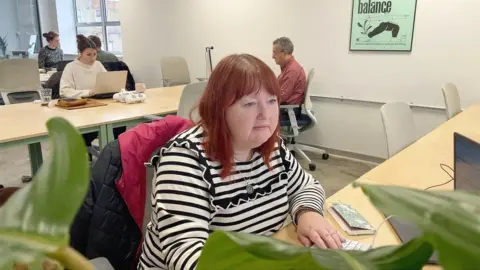

"We live in a small apartment and I'm sharing the working space with my husband who's also working hybrid," says Jill Parrish, who works for a market data consultancy in central London.

"It's a bit fraught. I have distractions like the washing machine, various household tasks - and my husband!"

But instead of resuming her two-hour commute to the City, she comes to co-working space Patch, near her home in Twickenham, south-west London, twice a week. Her subscription allows her eight visits a month to hotdesk.

Her employer pays half of her costs, because it agrees it's good for her productivity. She's part of a trend known as "working near home" - as opposed to working from home.

WeWork, once valued at $47bn (£38bn), saw a meteoric rise and fall. Late on Monday it filed for bankruptcy protection, affecting its business in the US and Canada

The firm said its co-working spaces remain open and operational, including in the UK. Its sites with their swish decor, tend to be very large, security-controlled, multi-floor buildings in densely packed inner-city areas.

By contrast hubs like Patch are located in residential areas, a walk away from people's homes.

A range of companies are vying to grab this market in local, community co-working hubs.

ARC Club is building a network around the outskirts of London. Platform 9 is creating similar places in Brighton. Edinburgh-based Desana has also raised millions for its concept, signing up existing community co-working spaces to create a national membership network, and then connecting large employers to this resource.

One of the reasons WeWork's fortunes suffered was that many of its users took to working from home during the pandemic. But while most office workers may not miss the commute, not everyone has found working from their kitchen table plain sailing either.

It can be a lonely place - or one filled with too many distractions, from pets to spouses.

Dirk Lindner

Dirk LindnerWorking near home represents a third way, argues Freddie Fforde, founder of Patch.

It has hubs in Chelmsford, High Wycombe and Twickenham, with future sites planned for next year outside the south of England, including one in the north.

His sites are designed to be community spaces where anybody can access the ground floor. They have cafés and event areas, which can be used for children's parties or workshops. Local businesses like bakers and flower sellers also do pop-up events.

But dozens of workers also use the upper floors of each building every day on either a hot-desk or fixed-desk basis, with access to meeting rooms and quiet booths. Others pay more for their own small, private office.

A key attraction is that working parents can be nearer to their childcare arrangements, whether that is a childminder, nursery or school, since this is typically close to home.

This is the incentive for Isabel Pollen, an actor-turned-performance coach, based in Twickenham. "My home and my seven-year-old daughter's school are just down the road," she says, "and my community of friends live here too, so I can invite them in for coffee sometimes."

One problem for WeWork, Freddie Fforde points out, is that its prime urban locations mean a very high proportion of its revenues - more than 70% - is spent on rent. That's not the case for smaller hubs because rent is cheaper in towns or on the fringes of cities. He thinks this model is more economically viable.

He is betting on companies using the money they've saved from reducing their office footprint to subsidise their workers coming to places like these.

Patch has secured venture capital funding from the founders of Innocent Drinks and PureGym to help grow its network.

But not all commercial property experts agree.

"The serviced-office sector is actually growing, despite WeWork's problems," says commercial property agent Duncan Campbell, of Campbell Gordon. The sector remains primarily based in city centres and business districts.

"[But] the far bigger trend," he reckons, "is actually that both blue-chip companies and SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) are pushing for workers to return to the office for better productivity."

The City of London Corporation recently reported a surge in demand for office space.

Oru Space

Oru Space Entrepreneur Vibushan Thirukumar has set up hubs called Oru Space in Sutton and East Dulwich in south London. Both of them are supported by the local councils who view them as good for the community.

The public spaces include a restaurant offering food from his native Sri Lanka and rooms with regular meditation and yoga classes.

His members can access these classes at a discounted rate, and some are open to all and free.

The space is as much a "wellness hub" as a co-working space, he says. In fact the East Dulwich building used to be an NHS mental health assessment centre.

He thinks avoiding the loneliness of working from home is a big draw, whether that is for freelancers, or the 40% of his members who are employees. As an antidote he hosts "Chatty Wednesdays", when members meet in the library room to socialise.

"We wanted to replace the commute and allow people to work amongst their neighbours," says Mr Thirukumar, "and when people spend more time locally, that means they reinvest their money in the local economy."

Oru Space

Oru SpaceHe doesn't believe the WeWork model was sustainable. "WeWork weren't really about co-working. They were a property-growth company, focused on growth, not retention. They only cared about aggressive growth. Talking about exit before you've built anything of value is always a recipe for disaster."

The companies building community, co-working hubs are certainly more idealistic than WeWork, saying they put a premium on the value they add to their neighbourhoods.

It's symbolic that many of these hubs are taking over buildings that used to bring communities together, like churches, council buildings or department stores, says Freddie Fforde, because they are finding new ways to bring people together, through remote work.