US savers get savvy ditching and switching banks

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA wave of transfers is hitting US banks, as a sharp rise in interest rates after years of low borrowing costs creates more opportunity for savers - and new challenges for banks.

Until recently, Claire, a software engineer, stashed all her money in a chequing account she had opened years ago as a university student. She let thousands of dollars build up there despite its paltry interest rate.

The prospect of earning 4% or more shook her out of her complacency. This month, she transferred $20,000 (£16,000) to a different bank offering a higher interest rate.

"I never paid attention. I just left my money in the account," says the 26-year-old, who lives in Massachusetts and credits a personal finance podcast with alerting her to better options.

"I don't want my money to just sit in one place. I want to make the most out of it."

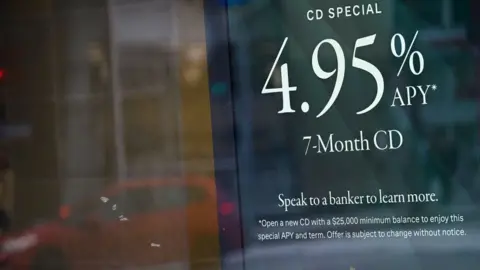

Banks have paid notoriously low rates on savings for years - something that has yet to change at many of the biggest firms, despite the US central bank hiking its benchmark rate from near zero to more than 4.75% in just a year.

But there are signs that the sharp climb may be starting to shake up the status quo - unsettling a financial system accustomed to relying on low-cost deposits as a key source of funding and profits.

Contributor

Contributor"It's a competitive market," Jeremy Barnum, chief financial officer of JPMorgan Chase told investors on Friday, as the firm reported that average deposits had fallen 8% from a year ago.

Roughly 30% of US bank customers moved money from their primary account to another bank in March, up from 27% in the previous year, according to a survey by consumer intelligence firm JD Power.

A third said they were making the switch for higher rates, up from a quarter a year earlier.

That's a "slow climb", says Paul McAdam, JD Power's senior director of banking. "But extrapolate this across millions of consumers and it makes a difference."

Questions about how banks will handle the change sharpened last month after the US was hit by the two biggest bank failures since the 2008 financial crisis.

In the weeks following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, billions of dollars in deposits shifted hands, jolting a system accustomed to savings serving as a stable source of funding.

While that rush appears to have subsided, many banks say they expect consumers to continue to hunt for the best deals, as online banking makes shifting funds easier than ever and rapid price inflation makes people unusually sensitive to erosion in the power of their savings.

"Consumers are more aware of how their returns stack up against the loss of buying power," says Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com, which has tracked interest rates offered to consumers for decades. "They have taken notice of the higher returns available at some banks and not others and have moved their savings accordingly."

Many people, like Claire, are switching allegiances to open new high-yield or money market savings accounts, which can pay interest rates of 3.5% or more, compared to the 0.24% average interest rate on a traditional savings account, according to data collected by Bankrate.

Others are shifting their money out of banks entirely, opting for other kinds of investments, such as US government bonds or money market mutual funds, which buy relatively low-risk short-term government and corporate debt and can offer rates north of 4.5%, but offered little advantage over a savings account when interest rates were low.

Reuters

ReutersThe moves led deposits held by banks in the US to fall last year for the first time in decades, dropping more than $200bn at the end of December from a year earlier, according to data from the Federal Reserve. Fitch expects deposits to decline by another $1.6 trillion this year.

"Banks and policymakers were ready for the deposit outflows that were happening through February. What is definitely the case now is we have increased uncertainty as to whether outflows will turn out to be bigger than historical norms," says Alexi Savov, professor of finance at New York University's Stern School of Business.

The decline in deposits so far is still consistent with what typically happens when interest rates rise.

Overall, the banking system remains flush with cash, reflecting the unprecedented surge in deposits during the pandemic, as savings rates increased and government assistance programmes fattened people's accounts.

But worries abound about what lies ahead for the economy as the funds available for lending shrink.

Analysts say some banks, especially the biggest, can afford to lose some of their outsize deposits, without a major hit to profit or activity.

But Prof Savov says the outflows will put pressure on others, especially smaller regional firms, squeezing profits and leading them to pull back their lending - with potentially serious ramifications for local economies and some business sectors, such as commercial property, where regional banks play a big role.

The recent bank failures caused a sharp acceleration in outflows from those smaller players, he notes.

Getty Images

Getty Images"It creates a much bigger risk of a bumpy landing, potentially a recession," Prof Savov says. "It's just such a live ball."

The growth of money market funds, which saw their holdings surge in the weeks after the banking crisis, has sharpened the removal of money from the economy, since the funds do not play a direct role in lending, while having the option of parking their holdings with the US central bank, says Steven Kelly, senior research associate at the Yale School of Management's programme on financial stability

Their growth also risks making the financial system more unstable, since the firms in charge of such investments are quick to flee at signs of trouble, unlike everyday depositors, who can count on the government to guarantee accounts up to $250,000, he adds.

"An insured depositor maybe won't run at the first sign of bad news," he says, but a money market fund is likely to "just disappear overnight".

If the economy encounters serious problems, the US central bank is expected to cut rates - a scenario many investors see as happening sooner following the bank panic.

That means the reshuffling of deposits, as people like Claire seek more for their savings, could prove short-lived too.