'Am I part of the problem?' The homeowners choosing not to sell

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDetroit-area homeowner Adam Hobart started looking for a new house last year with more bathrooms, a bigger yard for his dog and space for his ageing mother to join him.

But he has scrapped his search, after a surge in borrowing costs pushed the properties he was considering out of his budget.

Now the 38-year-old, who purchased his current bungalow five years ago and locked in a low interest rate on his home loan during the pandemic, says he's focused on saving and doesn't expect to move for at least another year.

"I've put my search a little bit mentally on pause," he says.

Adam's decision to put his search on hold is indicative of a shadow looming over the housing supply in the US, where 30-year fixed-rate mortgages are typical, and the sudden rise in interest rates has made it unusually costly for homeowners to upgrade, while limiting the savings they might gain in a downsize.

The dynamic is leading to a freeze-up among would-be sellers, keeping a lid on inventory and pressure on prices in a country already grappling with a shortage of homes and an affordability crisis.

"With rates hovering around 6.5%, it becomes very expensive to give up your home," says Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at brokerage Redfin, which is predicting that homes in the US will turn over at the lowest rate since the early 1980s this year, as potential sellers like Adam stay put.

Adam Hobart

Adam HobartThe US was already experiencing a decades-long decline in moving rates, raising alarm among some economists who see the shift as linked to a narrowing of economic opportunities.

The number of long-distance moves increased a bit last year, as the rise of remote work, a booming job market and ultra-low interest rates put in place to boost the economy when the pandemic hit in 2020 unleashed a buying frenzy.

But overall the share of Americans moving each year remained below 9% and Riordan Frost, senior research analyst at Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies, says he expects affordability issues tied to higher interest rates to limit home moves again in 2023.

The decline in moving, which he says has been driven by high housing costs over the last decade, is a big change for the US, which once stood out for having an unusually mobile population, with a moving rate more than double the current pace as recently as 1987.

Younger people and renters, who typically move more frequently, have seen especially sharp declines.

"There are reasons to not be upset about a lower mobility rate, which is that it could mean that people are satisfied in their houses - and we want that," says Dr Frost. "It could also mean that people are stuck in place."

The number of homes sold in the US plunged by roughly 17% last year, as rates hit their highest levels in 15 years, adding hundreds of dollars to the typical monthly mortgage payment and knocking out an estimated fifth of buyers, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Despite the drop in demand, prices still rose nearly 10%, as supplies remained tight.

Forecasts for what will happen next, as the critical spring selling season starts, vary widely.

The median price of homes sold in February dipped 0.2% compared with a year earlier - the first such decline in more than a decade.

Some analysts expect prices to continue to slide with at least one predicting a fall of as much as 15% this year.

But though some cities are seeing drops, the US overall has so far avoided the bigger falls seen in some other countries, as inventory remains near historic lows.

In Canada, for example, prices in February were down 19% year-on-year, while in Australia they have dropped almost 8%.

In the UK, the average price of homes sold in March fell 3% compared with 2022, according to the Nationwide.

"Even though demand has cooled, we still see there are not enough homes," says Nadia Evangelou, senior economist at the National Association of Realtors, which predicts prices will dip a modest 1.6% this year, despite mortgage rates hovering near 6.5% - roughly double what they were at the start of 2022.

Overall, prices jumped 42% nationally from 2019 to 2022, which means few long-time owners are facing a loss if they sell.

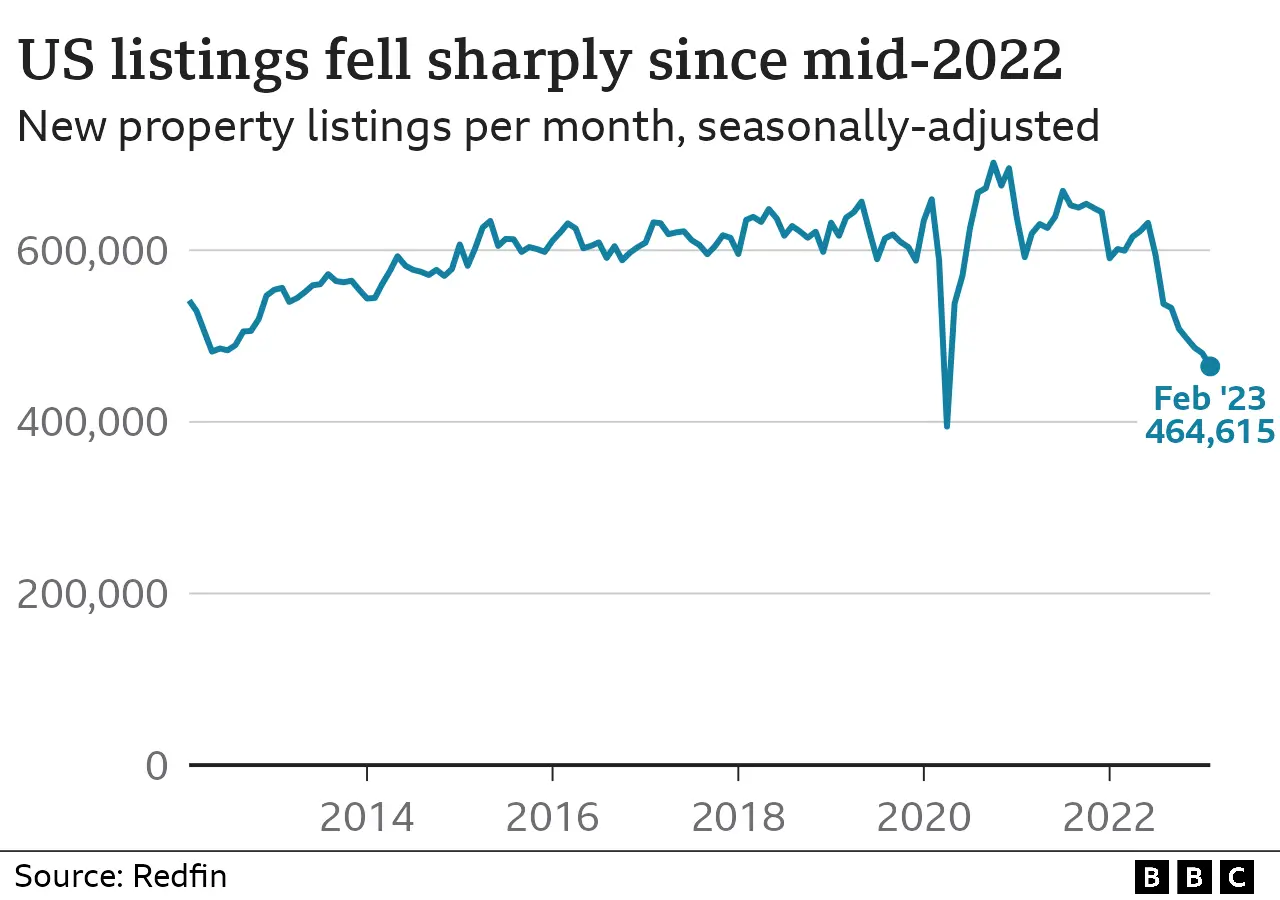

But the number of homes being put on the market has dropped sharply. Seasonally-adjusted figures from Redfin show there were just under 465,000 new listings nationally in February - the lowest level in more than a decade, except for the height of pandemic lockdowns in 2020.

"Buyers are jumping back in the fray as the new normal of rates are setting in. Homeowners who would typically sell their home, however, have the golden handcuffs of yesterday's rates making it much more attractive to stay put," says Rachel Mehmedagic, owner of Windermere Real Estate's office on Mercer Island in the Seattle region.

Ryan Boyle

Ryan BoyleSeattle has seen one of the biggest drop-offs in homes for sale, with the number of new listings falling more than 40% in February compared with a year earlier.

Seattle renter Ryan Boyle and his wife have been looking for a home to start a family for more than a year. At the start, they faced stiff competition and staggering prices. Though the frenzy appears to have subsided, he says properties that meet their needs and are within their budget remain few and far between.

"My wife spends four hours a day looking at houses. We've seen every listing and we're constantly watching the market," the 31-year-old says.

"If we find a place that is priced correctly, especially based on the interest rates, then we'd move on something. But I haven't felt that there's a tonne of inventory."

First-time buyers accounted for just 26% of home sales last year - the lowest number since the National Association of Realtors started tracking the figure.

Adam Hobart says he feels lucky he "got in the door before it closed" and sympathises with the hurdles faced by buyers trying to come after him. But he sees no easy fix to their problems.

If he does find a place, Adam says the monthly costs of his current home are low enough - about $900 - that he hopes he can hold onto it as a rental.

"Eventually, since I've got this low-interest mortgage, I can foresee paying that off and that turns into a part of a future retirement plan," he says. "I'm like, 'Shoot, am I part of the problem?' But also to some degree you have to look after yourself."