Why energy firm Bulb's collapse may cost you £200

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEnergy firm Octopus Energy is on track to buy collapsed rival Bulb which is being run by administrators after being bailed out by taxpayers.

You may not be one of Bulb's 1.6 million customers, but if you pay tax then you will be funding its rescue.

The total estimated bill is more than £200 for every UK taxpayer.

So how did a firm that was the poster child for the benefits of new competition in the energy market end up becoming the government's biggest bailout since the 2008 financial crisis?

The government's official budget forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), has said the support for the firm will cost the public around £6.5bn (although the government says the net cost will be lower).

There are four main reasons: bad regulation, bad luck, bad government policy and most likely some bad maths.

1. Bad regulation

Over the last two decades the energy regulator Ofgem, with the support of Conservative and Labour governments, prioritised stimulating competition in the energy market as the best way to bring down energy bills. The onetime monopoly of British Gas seemed a distant memory when looking at the proliferation of dozens of new providers competing via comparison websites and enabled by easy switching.

However, many of these companies had little or no shock-absorbing financial reserves. That was ok as long as they could pass on any rises in wholesale costs to their customers.

When a universally politically popular energy price cap was introduced at the beginning of 2019, the landscape changed. It introduced the risk that energy companies might have to buy energy at a higher cost than they could sell it.

Well run companies managed this risk by buying their energy well in advance so they could still survive under a cap set and monitored by Ofgem.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut some didn't do that.

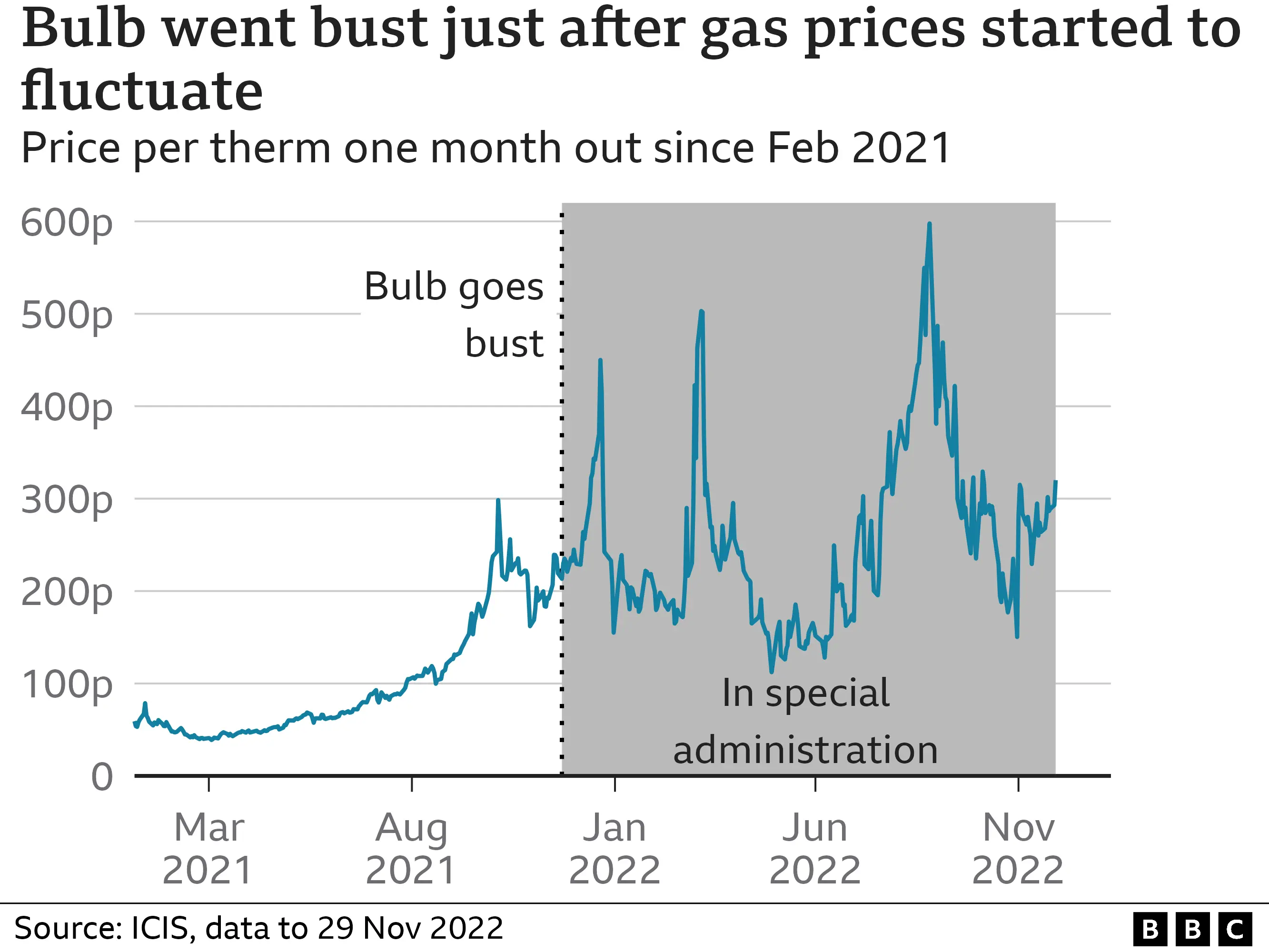

When energy prices started to skyrocket when world demand for oil and gas soared post-Covid, the difference between the wholesale price companies bought energy at and the lower price at which they were allowed to sell it, bankrupted dozens of companies which didn't have the financial reserves to absorb these losses.

This exposed the regulator's failure to pay due - or any - regard to the financial resilience of the companies it regulated.

Ofgem had a system whereby the customers of these small, failed companies were absorbed by the larger, surviving companies. The additional cost incurred by those companies as they had to buy more energy at high prices for new customers, was passed on to all consumer bills over time.

But Bulb was deemed too big for other companies to want to absorb and see another big hike to consumer bills at a time when energy costs were soaring.

So in November 2021 Bulb was nationalised and special administrators appointed to run it. The government hoped to sell the business by the following spring and set aside £1.7bn to buy the energy to keep supplying Bulb customers until that time.

2. Bad Luck

But worse was to come and energy prices rocketed again when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, sending any would-be buyers running for the hills.

The government found itself owning an energy supplier at the worst time in living memory.

Prices rose to five and then 10-times their pre-pandemic, pre-Ukraine rates at the same time as the energy price cap, set every six months, meant they were painfully exposed to the extreme volatility of wholesale energy prices.

3. Bad Policy

The reason more energy companies didn't go bust was that the well-run, financially-resilient ones had insured themselves ("hedged") against that volatility by buying the gas they needed for their customers well in advance.

But the Treasury has a long-standing reluctance to do this. The government prefers to self-insure against financial risk rather than pay a fee to profit making third parties. "We don't pay Aviva to insure battleships - so we don't pay financial institutions to insure financial risks," said one Treasury official.

But this is a preference, not a rule.

A former senior Treasury official told the BBC that "Treasury theology wouldn't rule it out".

So the government could have insured against rocketing prices but chose not to.

4. Bad Maths?

But even that is not the main driver of the whopping £6.5bn bill for Bulb. It turns out that, to date, the administrators of Bulb have spent less buying energy than the government originally forecast they would. Although the meter is still running on it, they have currently spent less than £1.2bn. It seems the vast majority of the estimated bill comes from Treasury assumptions about a complex set of moving parts.

To transfer Bulb back into private ownership, the government has to set aside money to protect the would-be buyer from taking on risks that might ruin the company (Octopus) acquiring it.

Estimating the cost of this post-sale support depends on taking a view on future wholesale energy prices, the level at which future retail caps are set, the amount of ongoing government bill support, and assumptions about how much money the acquirer will pay back to the government from any extra profits from its new customers over time.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIndustry sources have told the BBC that the government appears to have taken the most conservative/most pessimistic view on all of these factors. Even some in the Treasury seem unsure as to how the number was arrived at, while sources close to the current administrators have used words like "toppy" and "baffling".

Some energy companies argue it means that Octopus was getting an unreasonable and unfair level of government support to take it out of public ownership.

Lawyers in court argued it amounted to a massive sweetener - or "cash dowry" to Octopus.

Octopus hit back, saying other companies were offered the same chance to take on Bulb but walked away.

But crucially, say the objectors to the Bulb/Octopus deal, at the time they were asked to consider taking on Bulb, the government had not yet announced its Energy Price Guarantee which saw the government subsidising household bills, meaning millions of customers who would not have been able to pay, now could. This fundamentally reduced the risk of taking on more customers.

The deal currently in front of the courts for Octopus to take control of Bulb includes a profit sharing agreement which would see Bulb repay some of the government support over time if Octopus made a profit supplying Bulb's customers.

Estimates of the final likely bill range from "only" £3bn to £4bn, rather than the OBR's £6.5bn estimate.

"[The OBR's] cost figure does not include the full details of any deal drawn up as part of the process to remove Bulb from the Special Administration Regime," said a business department (BEIS) spokesperson. "Nor do the OBR figures include the financial support that will be repaid by the new entity in accordance with an agreed repayment schedule, so we still expect the net cost to taxpayers to be much lower."

Sources close to Octopus insist that the government needs to proceed quickly as Bulb's consumer satisfaction scores are plummeting, leaving the government and the taxpayer with an asset deteriorating in value.

Not over yet

The great energy bust of 2021 and 2022 may not yet be over. The Business Secretary Grant Shapps, recently wrote to the remaining suppliers urging them to reduce customer direct debits when they used less energy prompting some, including Centrica boss Chris O'Shea, to imply that some companies were essentially borrowing money from their customers to finance their operations.

Some have described the energy bloodbath as the greatest regulatory failure since the financial crisis. While it is probably fair to say that few could have predicted a tenfold spike in the price of gas, regulators are there to imagine the "what ifs".

Ofgem has promised a new regime where the financial resilience of market participants, rather than their sheer number, is top of mind.

Many will say that is something that a regulator should have been doing anyway.