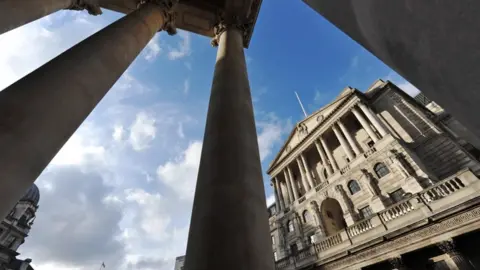

Risk of £50bn bond sale sparked emergency Bank of England move

BBC

BBCThe aftermath of the mini-budget could have seen a £50bn fire sale of UK government bonds by funds connected to the pensions industry, the Bank of England has said.

There was risk of a downward "spiral", it said, as increases in the cost of government borrowing hit the funds.

The Bank feared these funds would be forced to sell their government debt holdings, adding to the market turmoil.

The cost of borrowing saw record increases for two days, the Bank said.

The rise in borrowing costs over four days was "three times larger than any other historical move".

The Bank stepped in to calm markets last week following fears that some types of pension funds were at risk of collapse.

It pledged to buy up to £65bn of government bonds after the mini-budget sparked turmoil on financial markets and the pound plunged.

Investors had demanded a much higher return for investing in government bonds, causing some to halve in value.

The Bank said that the market in long-term loans to the government lasting three decades, known as 30-year gilts, saw two days where the effective cost of borrowing saw record increases, on its data which starts in 2000.

A letter from the Bank's deputy governor John Cunliffe to the Treasury Select Committee contains a diagram depicting the trigger for the interest rate shock as the "fiscal event", another name for the mini-budget, and that the nature of the move in the UK was not seen in the US or eurozone.

Jonathan Haskell, a member of the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee, also said in a speech on Thursday that "there was undoubtedly a UK-specific factor" in the market turmoil.

This contradicts the claims made by some government supporters that the mini-budget had nothing to do with last week's turmoil, which was instead caused by "global factors".

The UK's independent economic forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), had offered to prepare a draft forecast in time for the mini-budget, but the government did not take this up.

Mr Haskell added that the Bank uses OBR data in its own forecasts, and a "sidelined" OBR "generates more uncertainty by worsening everyone's information base".

The risk the Bank feared was that the funds connected to the pensions industry, known as Liability Driven Investments, would become forced sellers of their holdings of UK government debt, in an already troubled market.

A £50bn sale would represent four times the normal daily trade in the market, and would have pushed the effective cost of borrowing, or yield, even higher than 5%, leading to further problems. Before the mini-budget, this yield had stood at about 3.7%.

While individual defined benefit pension funds were not at risk, because they are guaranteed by the sponsoring company, it could have led to a wider financial stability challenge.

The Bank of England decided to intervene in the market last Wednesday, bringing down the effective borrowing cost from over 5% to under 4%.

As the Bank has eased off its interventions, on Thursday these costs had risen notably again, as high as 4.4%. These rates feed into the costs of long-term mortgages and business lending.

The Bank emergency intervention is due to end next week and it has so far bought a fraction of the government bonds it could have, spending just £3.7bn.

On Thursday, the Bank said it would wind down its bond buying in "a smooth and orderly fashion" once it felt the market was functioning normally again.

The Bank also said it is working with the UK's pensions and financial regulators to make sure that that investment strategies used by certain types of pension schemes can withstand market volatility.