Inflation: Why food prices matter for the US midterm elections

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe cost of food in the US is rising at the fastest pace since the 1970s, with grocery prices up 13.5% in the 12 months to September.

As elections approach in November and wages fail to keep pace, shoppers are feeling the pain. So when will it get easier - and will high prices shape how people vote?

Why are prices so high right now?

A carton of eggs in the US costs more than $3 today, more than twice what it was at the start of 2021, when US President Joe Biden took office. Beef and chicken prices have surged almost 20%, and a bunch of bananas runs 10% higher.

"It's very hard," says 78-year-old Edda Charbon. The New Yorker says she often finds herself returning items to the shelves that she used to buy, shocked by how much they cost. "Even to fry eggs - a little thing like that may cost a lot."

The price spikes started during the pandemic, when dining out plunged, demand for groceries surged and Covid outbreaks led to production issues.

Companies passed on higher costs they were facing, like higher wages and more expensive fuel.

Then, this year, the war in Ukraine disrupted supplies of fertilizer, wheat and other crops, sending global prices soaring. Bad weather has led to poor harvests, while outbreaks of bird flu have hit egg supplies.

When will food prices come down?

While restaurant prices have historically gone in only one direction - up - grocery prices do sometimes fall.

But for that to happen, supply has to get back in sync with demand.

There has been some good news on that front. Global food prices have eased in recent months, while oil prices have also dropped.

And as many like Edda cut back or switch to less expensive items, food companies, which have been passing on higher costs to customers while booking strong profits, may also find it harder to raise prices.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat's still unlikely to mean relief any time soon. Many firms such as Coca-Cola and Cheerios-maker General Mills told investors over the summer that they expect price increases to continue through the end of the year.

"The future is very uncertain," says Jayson Lusk, agricultural economist at Purdue University. "To the extent that we see lower agricultural commodity prices, lower energy prices - that will certainly help, but there are a lot of costs that happen after the farm - like labour and other issues, and those are harder to predict."

What has Joe Biden done to fight inflation, and what is the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022?

In the meantime, Americans consistently name the economy and rising prices as a top concern - and growing numbers say they are dissatisfied with President Joe Biden's performance, especially Republicans.

"He has not done a great job," says Romeisha Lowery, a 36-year-old former Trump voter from Texas, who says the rising costs of food, gas and other items had prompted her family to seek help from food pantries in recent months.

"I feel like within the past two years, we are way poorer then we were under the Trump administration."

Romeisha Lowery

Romeisha LoweryMr Biden has tried to respond, releasing unprecedented amounts of oil to bring down gas prices. When it comes to food, he's ordered investigations of competition in the meat industry, boosted support for farmers to buy fertiliser, and hosted a summit on nutrition and hunger.

Democrats also passed the so-called Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. But while it may have been savvy politics to claim it is about reducing price increases, most analyses suggest the law - which commits billions to fighting climate change and enacts a new minimum tax on companies among other measures - will have negligible impact on inflation.

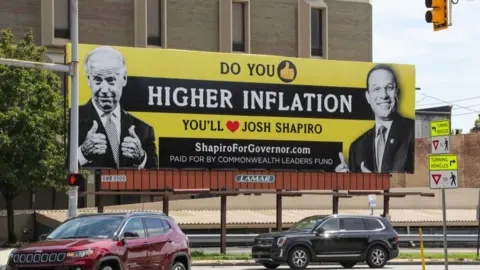

Republicans have seized on inflation as a winning issue, with adverts like one from Representative Don Bacon of Nebraska in which he serves so-called "Biden Burgers" to his wife - tiny hamburgers that he attributes to the high prices forcing people to cut back.

What do high food prices mean for the midterm elections?

The midterm elections, which are scheduled for November and will determine who controls Congress and the leadership of many states, are known for relatively low voter participation, with parties focused on driving turnout among their core supporters.

The party of the president typically loses seats. But many Democrats are hoping that the elections won't be as bad as once feared, even though the economy is working against them.

For one thing, there are fewer competitive races this year than in prior elections.

For the Democratic base, polls also suggest that inflation concerns have been overshadowed by the fight over abortion - which returned to the spotlight after the Supreme Court struck down the constitutional right to abortion in June - as well as worries about democracy generally, which some attribute to former president Donald Trump's involvement in politics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor Republicans, the economy remains key, especially as the price of gasoline - which looms larger than food prices in the public imagination - has started to tick higher, after dropping this summer. But candidates are also focused on issues that appeal to their base, like immigration.

"It's too risky to just run on gas prices," says pollster Lee Miringoff, director of the Marist Poll. "Perceptions of it change... and you don't want to be caught as a one-issue campaigner."

Polls show views of the economy are strongly tied to political leanings, with those on the right more likely to rate inflation as important - and to perceive the problem as worse.

Mr Miringoff said many voters have already made up their minds - and parties will be focused on "raising the stakes" to compel their supporters to the polls: "We're not going to see a lot of persuading or mind changing. We're going to see efforts to raise the language."