Direct sales: 'My dream job turned into a nightmare'

BBC

BBCMatt stood, phone in hand, taking photos of his hair on the floor. His topknot had just been cut off as a forfeit for losing out on a challenge to a colleague at the direct sales company for which he worked in 2018.

Fail to make as many sales as your colleague door-to-door, or on the street? There were consequences, which included eating chillies, being slapped with a fish, or doing press-ups in front of the office.

Matt says it never crossed his mind not to do the forfeit due to the peer pressure from colleagues. "You realise it's weird but because you're in that bubble, it normalises itself."

He told his mum and dad very little about his new role - from working up to 80 hours a week, to earning commission only - because of a sense of embarrassment.

He says the job was framed as a junior executive role in sales and marketing. Quick progression was a big selling point, with the promise of branching out and owning his own direct sales company and earning six figures within a year.

Watch The Dark Side of Direct Sales on BBC iPlayer, or listen on BBC Radio 4.

"That's more money than any graduate scheme at the time," says Matt, now 25. "I was hooked. I was all in."

A year-long BBC investigation, based on the experiences of dozens of ex-sales agents, suggests Matt's story, while an extreme example, was not unique.

It revealed concerns around exhausting working conditions, low pay and how some companies have been exploiting young people with little knowledge of the job market.

After Lauren, now 20, lost her job bartending in London during the pandemic, an online message about a marketing vacancy seemed like a dream come true.

During an interview, the director of the company asked what she would like to achieve in life. "I said: 'Well, I'd love to retire my mum, I'd love to be able to drive a nice car.'"

Lauren says she was told that would be easy if she followed in her manager's footsteps.

Like Matt, she was hooked by the dream of entrepreneurship.

She suggests the hustle culture - the idea of becoming your own boss and prioritising work above all else - and its prevalence on social media had a part to play, but says she was willing to "grind" to achieve her goals.

Lauren's parents questioned the new role. "But I was so defensive," she says. "I told them that they weren't seeing 'the vision'." But the reality of the job quickly set in.

Drawn in by descriptions of immediately earning £300-400 a week, Matt says he found out on his induction day that the role was commission-only. He was asked to register as self-employed, which meant no minimum wage, paid holiday, or sick pay.

Determined to make a success of it, Matt says he tried his best to sell to customers on the street, working about 12 hours a day, six days a week.

But over the 14 months he worked there, he made only £7,900. Between having to pay for travel and accommodation during "road trips" - to sell in other towns or cities - he says he maxed out his overdraft and credit card.

On one occasion, he started crying in front of a manager who told him off for his dishevelled appearance. "I said, 'I can't afford shampoo, I can't afford hair gel.' So I'd had to use hand soap to try and make [my hair] look decent."

What are direct sales jobs?

- Direct selling is a way of marketing goods or services directly to shoppers, typically away from shops and face-to-face

- It can include things like door-to-door sales, selling to passers-by on the street or from a pop-up stand - as well as some online sales

- According to figures from market research firm IBISWorld, the industry will draw in sales of £2.6bn in the UK in 2022-23

- Although sales were affected by Covid lockdowns, it suggests they have rebounded since and more people joined the sector during the pandemic

For Lauren, it became clear at her second interview that she would be doing door-to-door sales. It was then that she was also told she would need to register as self-employed, earning commission only.

"If you put in the work, you won't even be on the doors for long," she says she was told, referring to the promise of moving up the chain.

She describes the first day selling as "horrific", being instructed by her team leader to run door-to-door, waiting no longer than three seconds at each one.

"I came into the office limping because my feet were swollen."

She says the breaking point came after three weeks, when she wasn't able to take a toilet break during her period, and bled through her clothes. She describes "begging" a manager to find somewhere to change.

Lauren says he eventually agreed. "He said: 'You're not giving 100%.' He asked: 'Do you even want this? Do you want to retire your mum? Your period can't stop you from doing that.' I just felt so humiliated."

A spokeswoman for the company Lauren worked for said it does not tell sales agents that there are "no toilet breaks or lunch breaks".

But describing the experience overall, Lauren says: "I don't want to sound dramatic, but it was kind of like selling your soul."

A 'middleman'

Something else links Matt and Lauren's experiences: a company called Credico, one of the biggest players in the direct sales industry in the UK.

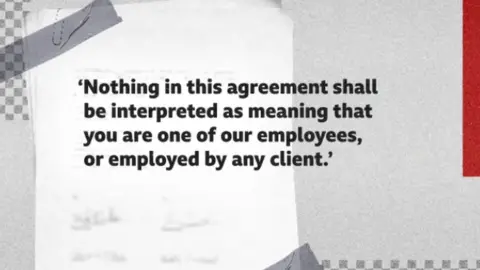

It is a company that essentially acts like a middleman. It contracts smaller sales companies, which get their recruits to go out and sell on behalf of big-name brands.

Credico was originally set up in Canada and boasts up to 15,000 sales agents working for its partner companies worldwide.

It says it now has more than 100 sales companies in its UK network, most owned by people who started out as sales agents themselves.

Matt says Credico was described to young recruits as "like Uber". "We were the taxi drivers, and the passengers were the clients. So Credico connect us and the clients together, they would give us the training materials and they will act as a go-between."

Despite the fact they were self-employed, many of the sales agents at these smaller companies told the BBC they felt a "lack of control" about when and where they would go and sell. "None of it was on my terms," Lauren says.

And court documents from a case brought by Credico for competition reasons last year suggest it does direct some of what the independent offices do.

For example, it provides the wording of the agreements that sales agents must sign when they are joining up to sell in its "network".

Several experts called this structure into question.

They criticised the working conditions described, as well as the fact that some job adverts for these companies outline a base salary, calling it "deeply misleading".

Employment lawyer Luke Menzies said there was a risk sales agents were being "taken for a ride without realising it".

"It seems to me, from what I've seen, that [sales agents] would have the right to go to an employment tribunal and say, 'I want my national living wage, I want my holidays.' And they would have the right to bring that claim."

But he said ultimately the responsibility for these sales agents would lie with the smaller companies in the network.

Labour MP Darren Jones, who chairs the House of Commons Business Committee, said he believed workers were being exploited.

"They are being exploited because they think they're signing up for an exciting job with a good salary that gives them prospects and actually, they arrive at the office and they're told they're self-employed, commission-only, door-to-door salespeople."

He also questioned why reforms aimed at helping vulnerable workers, promised as part of the 2019 Queen's Speech, have not yet materialised.

A government spokesman said new employment status guidance had been introduced, acting as a one-stop-shop for businesses and people to understand which employment rights apply to them.

"Exploitative practices have no place in our society, and we will investigate cases of malpractice," the spokesman added.

A Credico spokesman said: "Individuals are all engaged as independent contractors directly by independent sales offices, using a contract that is written using plain language to make it very clear that the individual will be self-employed."

It said standard pay and contracting models, which are common in the industry, were used.

"The contractors enjoy the flexibility that self-employment brings, as they are free to work the hours and days they choose, with many working less hours than a standard five-day week."

Credico also pointed out that it operates a whistleblowing programme for workers to flag concerns. Its spokesman added that the well-being of contractors was "extremely important to them".

As for Credico's clients, it is still an approved supplier for Shell Energy, but a spokesman said it has not used its services since October 2021.

The National Deaf Children's Society said it was not aware of the allegations and had launched an investigation. A spokesman added any malpractice will be treated "extremely seriously".

"It is crucial that any fundraising carried out for us is respectful to both the public and anyone working on our behalf," he said, adding that the charity has "sector-leading" safeguards.

TalkTalk told the BBC it "no longer" has a relationship with Credico, but described the practices uncovered as "shocking".

'You will get there'

Matt now works in sales in a salaried job. Meanwhile, Lauren describes the skills she gained in direct sales as helpful in finding a marketing job where she's happy.

But she added: "I want young people to be aware. Please don't get caught up in the hustle and the go-getter lifestyle. You will get there 100%. Don't feel like you have to rush it."

For details of organisations offering advice and support, go to BBC Action Line.

Follow reporter Lora Jones on Twitter.

Watch The Dark Side of Direct Sales on Tuesday, 23 August at 20:00 BST on BBC Three or BBC iPlayer, or listen on BBC Radio 4.