Europe is prepping for a trade war no-one wants

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn recent weeks I have been hearing a lot - both publicly and privately - from EU leaders, and from the chief executives of some of the region's biggest companies. No wonder. They've had a lot on their plate with events in Ukraine, a transformation of their energy supply lines, and the prospect of knock-on effects, including possible recession.

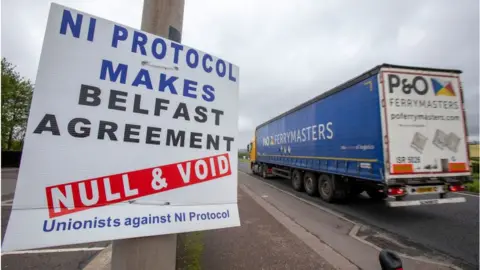

But I found many were also planning for the possibility of a major deterioration in trade relations with the UK, if the UK makes unilateral changes to the Brexit deal relating to Northern Ireland, and if those moves are deemed illegal.

Herbert Deiss, the chief executive of Europe's biggest carmaker, Volkswagen, told me he recently hosted high level discussions with the British ambassador to Berlin about the possibility of a trade war.

"There's a lot of communication going on. And there's also a dependency," he told me. "We have a British brand, Bentley, which is doing extremely well… also the UK is our biggest export market in Europe for the premium brands for VW and Audi ... so I think there will be, let's say, a mutual interest now to keep [trade] open."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut while that's what everyone wants, there's a quiet recognition that it might not be what they get.

At a recent private lunch one European leader, asked whether they thought that the difficulties over Northern Ireland could lead to a trade war, curtly answered "yes". In this particular leader's eyes, there was genuine shock that the pragmatic solution, agreed by both sides, could be ripped up. And the perception is that the risk from a trade war of doing "harm to your country" arises principally from internal party politics, rather than substantive concerns about Northern Ireland.

The Polish Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, told me trade wars are a "lose-lose situation". And he suggested the key antagonism over which he was trying to find compromise was between Paris and London.

"We will try to calm down the situation between France and the United Kingdom as much as possible, because I believe that only Putin and our enemies will be happy with yet another disagreement between such close partners as the United Kingdom and the European Union," he said.

At the same event the Irish Taoiseach, Micheál Martin, told me that "hopefully" such a fate would be avoided because a trade war would be "shocking" and "unnecessary".

Asked if the EU was preparing lists of UK goods against which to levy tariffs, Mr Martin told me: "We're not going to get into the detail of anything like that, because hopefully, that's something we don't ever have to contemplate. For now, I'm simply saying, and I've been consistently saying, get down there, get into the tunnel, UK government and EU, negotiate and get the technocrats in there."

In subsequent weeks Irish diplomats have walked the corridors of Europe, warning about what they see as a "low point" in EU-UK relations, and they say Berlin and Paris back a robust response.

Maximum political pressure

Work is going on behind the scenes.

In recent trade wars with the US for example, the EU (with the UK as a then-member participating) focussed retaliation on the most political of pressure points - Harley Davidson bikes, Levi jeans and Jack Daniel's whisky, and Florida's orange juice.

The US in turn focussed on the UK's famous exports of cashmere and whisky. All were deliberately chosen to maximise the political pressure and the headache in swing states. The equivalent process for the UK could focus on car exports from the North East, fishing and agricultural exports.

Then there is the question whether the UK would reply in kind, or at all. The Brexit opportunities minister Jacob Rees-Mogg has called the idea that the EU would levy tariffs as an "act of self harm". For the EU and the UK, suffering from low growth and high inflation on all sides, a trade war threatens to worsen both.

As Mr Deiss made clear, British diplomats have been meeting with German automakers to defend their interests, which suggests that there is a fear of tit-for-tat tariffs on carmakers.

European leaders are privately getting into gear, but they would have to agree the level and scope of any retaliatory action. None of this is certain, but business groups fear even the threat of this process will be enough to deter some investment. The process of escalation is certainly being prepared.