Cost of living: Lessons from history about how we spend

Leeds Museums and Galleries

Leeds Museums and GalleriesIn 1967, in a field near the village of Cridling Stubbs in North Yorkshire, a pot containing more than 3,300 Roman coins was unearthed.

The hoard of copper coins from the 300s AD were still in the jar, buried upright, with a makeshift lid on top.

"We do not know for certain why they were buried there, and why nobody ever came back to find them," says Kat Baxter, Leeds Museums and Galleries' curator of archaeology and numismatics.

"That is the beauty of them - we do not know the answers. It is very mysterious."

We may not have the answers, but there are theories. The coins not only help us think about what wealthy people were doing with their cash nearly 2,000 years ago but may also frame some of the debate about the cost of living and cash today.

Security worries

The Cridling Stubbs hoard may have been buried for religious reasons, as some kind of offering to the gods.

Another possibility, is that it was hidden somewhere thought to be safe in a time before banks and building societies, particularly if the owners felt their money might be taken during a time of conflict.

"These were the security worries of the time. We have the same worries today but they just take a different form," Ms Baxter says.

Fraudsters steal £4m a day from people in the UK, so protection against such cons is high on the agenda for the finance industry and its customers.

Leeds Museums and Galleries

Leeds Museums and GalleriesThe Cridling Stubbs hoard is among more than 400 objects on display at the Money Talks exhibition, which runs at Leeds City Museum until 26 June.

As well as money security, the exhibits explore subjects including how money has been used in toys and play, the evolution of banking, and different examples of currency used around the world.

"Everyone has a relationship with money in some way," Ms Baxter says.

Our relationship with money is being tested at present, not only through the rising cost of living, but also in the changing way we pay for things.

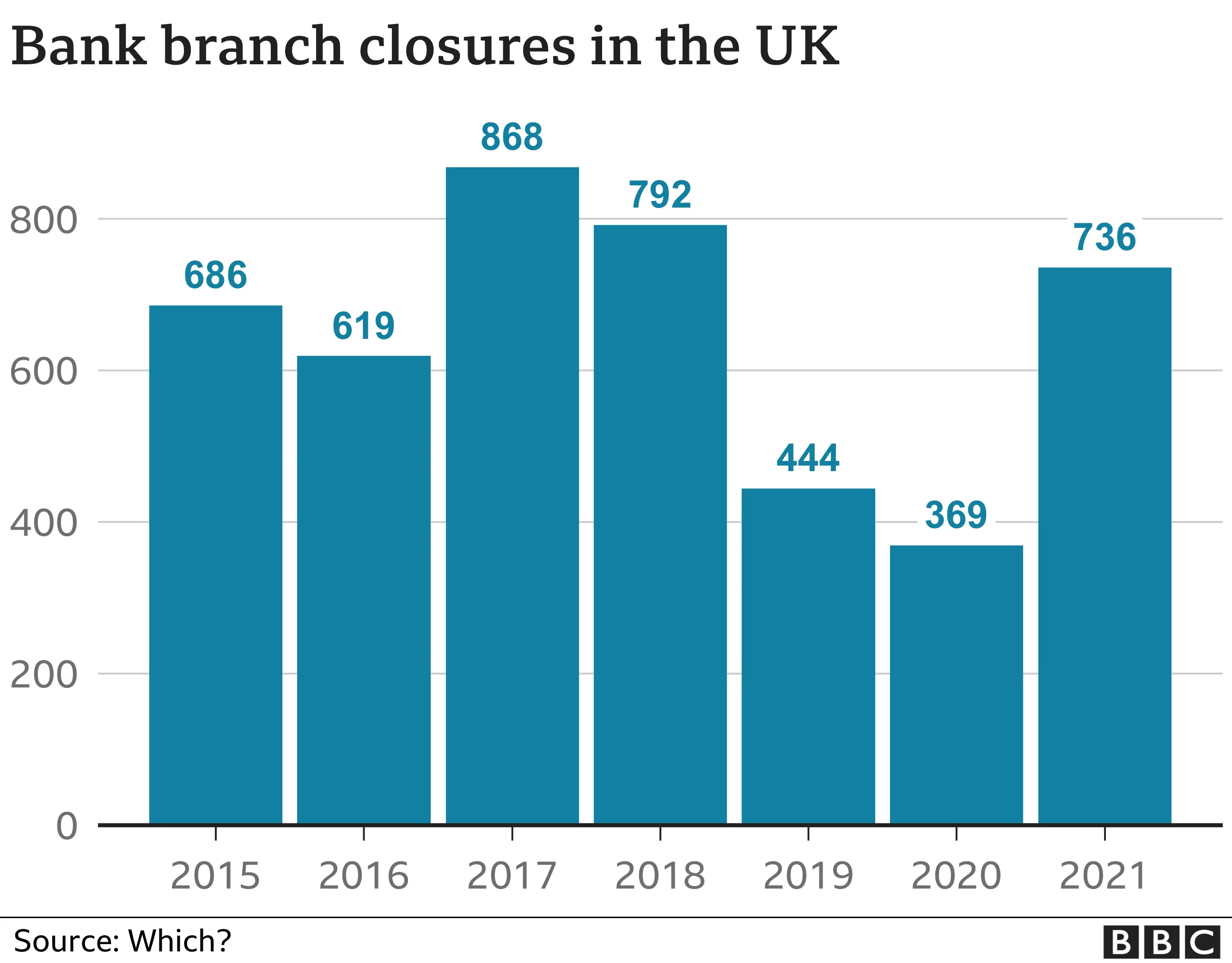

Since 2015, according to the consumer group Which?, some 4,685 bank branches have shut their doors.

A further 226 are already scheduled to close by the end of the year, it says, while the rate of closures in rural areas has outstripped those in urban areas.

People are increasingly using their smartphones and computers to manage their finances. Cards are now a much more common method of transaction than notes and coins.

However, Which? has warned that a move to a cashless society would leave millions of people "cut adrift". The government declared in the most recent Queen's Speech that it would legislate to ensure people had access to cash withdrawal and deposit facilities within a reasonable distance of home.

The exhibition in Leeds confirms there are plenty of examples through history of changing ways of paying for things.

Take, for example, the kind of items used as currency. In one display case sits a finely polished and ground axe head. It was probably never used to chop anything, but would have been used in some kind of transaction - a bit like bartering.

Ms Baxter points out that there would be a wider cultural impact if notes and coins were to disappear entirely.

One part of the exhibition examines how cash is used as a lucky charm in many ways - from popping it into the shoe of a new bride, to embedding it into necklaces.

"Going cashless does not just mean losing physical coins, it means losing a number of traditions too," she says.

Modern wearables

Less of a charm and more of a convenience is the way payment is often embedded into the things we wear and carry nowadays.

Using a smartphone or a watch, many of us will routinely tap to pay for items, or a bus or train fare,

Perhaps we are happy to lose some of the traditions and physicality of cash?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA recent survey by the card issuing platform, Marqeta, found that 77% of respondents aged 18 to 24 were confident enough in contactless payments to leave their wallet at home and go out with just their phone.

"While the pandemic was the catalyst for the shift to contactless and mobile wallets, it is the convenience, security, and speed of these payment options that have made them sticky," says Anna Porra, Marqeta's European strategy director.

Although she says these so-called intelligent mobile wallets are still in their infancy.

Diners are already paying at a restaurant by scanning a QR code on their phone at the table and settling the bill, without ever having to call over a waiter. Soon, she says, we will be standing at a bus stop and scanning QR codes for something we might be able to buy nearby.

The most significant developments will come, she suggests, when our devices not only act as a payment mechanism but also use artificial intelligence to prompt us with ways to manage our finances.

The merging of payments and financial services could even give information to businesses of our worthiness to buy something on credit, and guide consumers on the way to pay and whether it is affordable.

So-called super apps in the US and China already branch out into identifying what financial products might be available to consumers, as well as providing other services such as food, hotels and taxi options.

Ms Porra says widespread adoption of intelligent wallets will only come if providers also offer widespread education, to ensure users can be confident and have control over what is being suggested.

So, in the end it comes back to trust and security - not so different to the thought processes of someone burying a pot of coins in North Yorkshire nearly 2,000 years ago.