UK wage growth lags rising cost of living

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUK wage growth continued to lag behind the rising cost of living between October and December, figures show.

Wages rose, but when taking inflation into account, pay showed a 0.8% fall from a year earlier, said the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Latest figures also show that the unemployment rate fell to 4.1% while job vacancies hit a fresh record high.

There are signs that these pressures might feed through to faster wage growth in the coming months.

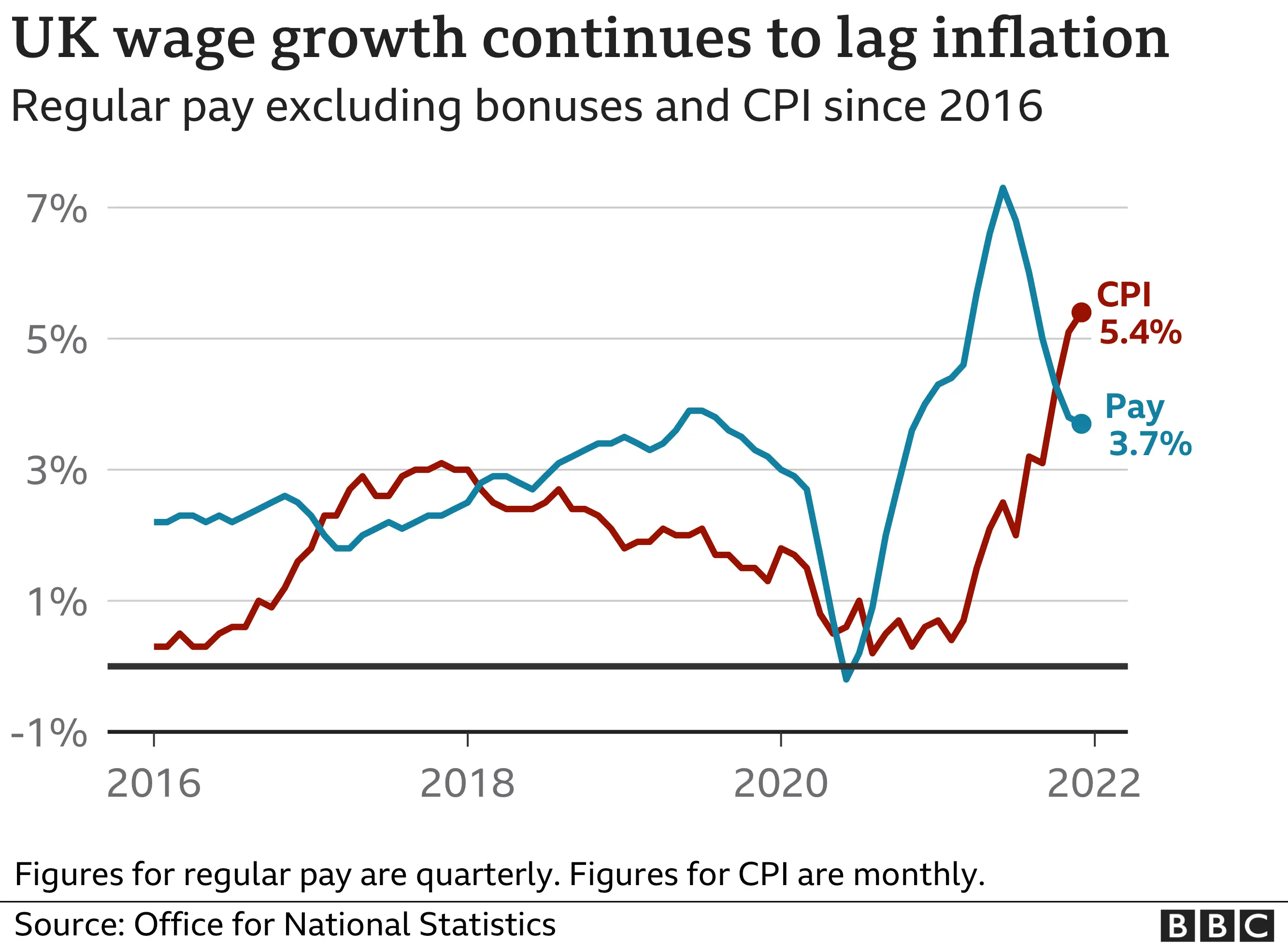

According to the ONS, employees' regular pay, excluding bonuses, grew by 3.7% between October and December from a year earlier - which is high compared with rates seen over the last decade.

However, the rising cost of food, energy and household goods has pushed inflation up by 5.4% in the 12 months to December. The ONS said real wages in the October to December period fell by 0.8% from a year earlier.

The Bank of England has warned this squeeze on workers will get worse, with inflation set to rise above 7% this year.

But the ONS said early estimates suggest employers are starting to push up wages further and faster in response.

It said that for workers on payrolls in January, median monthly wages increased by 6.3% compared with the same month last year, and they were 10.3% higher than before the pandemic in February 2020.

It added that wage rises for payrolled workers last month appeared to easily outpace inflation in some industries, such as science, finance and insurance, information and communication, and hotels.

Employers are having to increase salaries as they face a continuing shortage of workers.

Meanwhile the number of job vacancies between November and January hit another record of 1.3 million, the ONS said, with most industries finding it harder to recruit.

"The good news is that the UK economy is continuing to create jobs," said Matthew Percival, director for people and skills at the CBI.

"The bad news is that businesses are struggling to hire and pay is failing to keep up with inflation."

'Eye-watering'

Lee Powell, chief executive of GMI Construction Group, which employs 200 people in Leeds, told the BBC that the combination of inflation and skills shortages was a "headache at the moment".

"In the construction industry we've seen unbelievably rapid inflation across materials... and we're in a situation now where the demands for wage increases are somewhat eye-watering.

Getty Images

Getty Images"You'd automatically assume you could pass those prices straight on to the developer or to the end user but it's not as easy as that."

The governor of the Bank of England recently sparked controversy when he urged workers not to ask for big pay rises, to help stop inflation from rising out of control.

Andrew Bailey said that while it would be "painful" for workers to accept that prices would rise faster than their wages, he added that some "moderation of wage rises" was needed to prevent inflation becoming entrenched.

The GMB union branded the idea a "sick joke" while the government distanced itself from the comments.

Earlier this month, the Bank of England raised interest rates to 0.5% in an attempt to tame inflation.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist for Capital Economics, said the Bank was likely to take a more aggressive approach to rate increases this year and next given the economic picture.

"Employment has recouped the falls after the furlough scheme, the unemployment rate has fallen to pre-Covid levels, job vacancies are at a record high and wage growth is rising," he said.

"That's a recipe for more interest rate hikes, perhaps from 0.5% now to 1.25% this year and to 2% next year."

The latest estimates of wage increases for payrolled employees appear to confirm the Bank of England's fear that pay rises are taking off - one of the biggest reasons they've raised interest rates twice in a row.

While they are early estimates and subject to revision, they suggest that pay in January was up by just over 10% compared with February 2020. That is the first time we've heard of double-digit pay rises, even over two years, in a very long time.

Part of the reason is the tightest labour market we've had in living memory. Staff quit their jobs at record rates to take a better offer from another employer. Firms that want to keep people are having to pay more to retain them.

This is hard to reconcile with the more reliable but less up-to-date quarterly figures, showing pay rises at 3.7%, lagging price inflation. But statistical confusion will work itself out over time. Meanwhile, these figures will do nothing to discourage the Bank of England from raising interest rates a third time the next time its interest rate setters meet.