The underwater 'kites' generating electricity as they move

Minesto

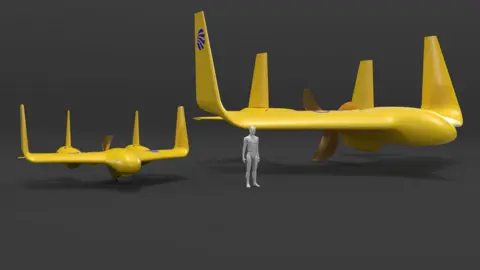

MinestoA pair of sleek, winged machines are "flying" - or at least swimming - beneath the dark waters of the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic.

Known as "sea dragons" or "tidal kites", they look like aircraft, but these are in fact high-tech tidal turbines, generating electricity from the power of the ocean.

The two kites - with a five-metre (16ft) wingspan - move underwater in a figure-of-eight pattern, absorbing energy from the running tide. They are tethered to the fjord seabed by 40-metre metal cables.

Their movement is generated by the lift exerted by the water flow - just as a plane flies by the force of air flowing over its wings.

Other forms of tidal power use technology similar to terrestrial wind turbines but the kites are something different.

The moving "flight path" allows the kite to sweep a larger area at a speed several times greater than that of the underwater current. This, in turn, enables the machines to amplify the amount of energy generated by the water alone.

An on-board computer steers the kite into the prevailing current, then idles it at slack tide, maintaining a constant depth in the water column. If there were several kites working at once, the machines would be spaced far enough apart to avoid collisions.

The electricity is sent via the tethering cables to others on the seabed, and then to an onshore control station near the coastal town of Vestmanna.

Minesto

MinestoThe technology has been developed by Swedish engineering firm Minesto, founded back in 2007 as a spin-off from the country's plane manufacturer, Saab.

The two kites in the Faroe Islands have been contributing energy to Faroe's electricity company SEV, and the islands' national grid, on an experimental basis over the past year.

Each kite can produce enough electricity to power approximately 50 to 70 homes.

But according to Minesto chief executive, Martin Edlund, larger-scale beasts will enter the fjord in 2022.

"The new kites will have a 12-metre wingspan, and can each generate 1.2 megawatts of power [a megawatt is 1,000 kilowatts]," he says. "We believe an array of these Dragon-class kites will produce enough electricity to power half of the households in the Faroes."

Minesto

MinestoThe 17 inhabited Faroe islands are an autonomous territory of Denmark. Located halfway between Shetland and Iceland, they are home to just over 50,000 people.

Known for their high winds, persistent rainfall and rough seas, the islands have never been an easy place to live. Fishing is the primary industry, accounting for more than 90% of all exports.

The hope for the underwater kites is that they will help the Faroe Islands achieve its target of net-zero emission energy generation by 2030.

While hydro-electric power currently contributes around 40% of the islands' energy needs, wind power contributes around 12% and fossil fuels - in the form of diesel imported by sea - still account for almost half.

Mr Edlund says that the kites will be a particularly useful back-up when the weather is calm. "We had an unusual summer in 2021 in Faroes, with about two months with virtually no wind," he says.

"In an island location there is no possibility of bringing in power connections from another country when supplies run low. The tidal motion is almost perpetual, and we see it as a crucial addition to the net zero goals of the next decade."

Minesto has also been testing its kites in Northern Ireland and Wales, where it plans to install a farm off the coast of Anglesey, plus projects in Taiwan and Florida.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

The Faroe Islands' drive towards more environmental sustainability extends to its wider business community. The locals have formed a new umbrella organisation - Burðardygt Vinnulív (Faroese Business Sustainability Initiative).

It currently has 12 high-profile members - key players in local business sectors such as hotels, energy, salmon farming, banking and shipping.

The initiative's chief executive - Ana Holden-Peters - believes the strong tradition of working collaboratively in the islands has spurred on the process. "These businesses have committed to sustainability goals which will be independently assessed," she says.

"Our members are asking how they can make a positive contribution to the national effort. When people here take on a new idea, the small scale of our society means it can progress very rapidly."

One of the islands' main salmon exporters - Hiddenfjord - is also doing its bit, by ceasing the air freighting of its fresh fish. Thought to be a global first for the Atlantic salmon industry, it is now exporting solely via sea cargo instead.

According to the firm's managing director Atli Gregersen this will reduce its transportation CO2 emissions by more than 90%. However it is a bold move commercially as it means that its salmon now takes much longer to get to key markets.

For example, using air freight, it could get its salmon to New York City within two days, but it now takes more than a week by sea.

Hiddenfjord

HiddenfjordWhat has made this possible is better chilling technology that keeps the fresh fish constantly very cold, but without the damaging impact of deep freezing it. So the fish is kept at -3C, rather than the -18C or below of typical commercial frozen food transportation.

"It's taken years to perfect a system that maintains premium quality salmon transported for sea freight rather than plane," says Mr Gregersen. "And that includes stress-free harvesting, as well as an unbroken cold-chain that is closely monitored for longer shelf life.

"We hope, having shown it can be done, that other producers will follow our lead - and accept the idea that salmon were never meant to fly."

Back in the Faroe Island's fjords, a firm called Ocean Rainforest is farming seaweed.

The crop is already used for human food, added to cosmetics, and vitamin supplements, but the firm's managing director Olavur Gregersen is especially keen on the potential of fermented seaweed being used as an additive to cattle feed.

He points to research which appears to show that if cows are given seaweed to eat it reduces the amount of methane gas that they exhale.

"A single cow will burp between 200 and 500 litres of methane every day, as it digests," says Mr Gregersen. "For a dairy cow that's three tonnes per animal per year.

"But we have scientific evidence to show that the antioxidants and tannins in seaweed can significantly reduce the development of methane in the animal's stomach. A seaweed farm covering just 10% of the largest planned North Sea wind farm could reduce the methane emissions from Danish dairy cattle by 50%."

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayThe technology that Ocean Rainforest uses to farm its four different species of seaweed is relatively simple. Tiny algal seedlings are affixed to a rope which dangles in the water, and they grow rapidly. The line is lifted using a winch and the seaweed strands simply cut off with a knife. The line goes back into the water, and the seaweed starts growing again.

Currently, Ocean Rainforest is harvesting around 200 tonnes of seaweed per annum in the Faroe Islands, but plans to scale this up to 8,000 tonnes by 2025. Production may also be expanded to other areas in Europe and North America.