Gen Z battles to bring back unions, one Starbucks at a time

Michael Sanabria

Michael SanabriaStressful working conditions, a lack of training, and slim hopes of a pay rise are just some of the things that anger Jaz Brisack, 24, about working at Starbucks in Buffalo, New York, USA.

Yet it was the "inability to negotiate as equals" with the coffee giant that pushed the barista and about 80 of her colleagues to do something out of the ordinary last month: call for a vote to form a union.

Currently none of Starbucks' 8,000 US cafes is unionised, meaning the world's biggest coffee house chain is under no obligation to negotiate with staff over pay and conditions. But the baristas hope to change that at three cafes in Buffalo, setting a precedent that could disrupt the firm's business practices much more widely.

"Starbucks likes to say they don't consider us employees, they consider us 'partners', but we have no power in that partnership," says Ms Brisack, who is part of the employees' organising committee, Starbucks Workers United.

"But if we can build actual worker power for baristas, then we can change not just Starbucks and make it the best it can be, but help make the whole services industry better."

The campaign at Starbucks is just the latest example of a resurgence in US labour activism after decades of decline. Politics, pandemic-related frustrations, and younger, more engaged workers are driving the change.

In 2021 alone, employees from Amazon warehouse staff to New York museum curators have sought to unionise for the first time, while there have been months-long strikes by coal miners in Alabama and grocery workers at food giant Mondelez International.

Ms Brisack and her colleagues - all of whom are under 30 - have applied to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to hold elections at the cafes in the coming months and think they have comfortable majorities to win. But Starbucks, they say, is doing everything it can to stop them.

Michael Sanabria

Michael SanabriaThe chain has hired law firm Littler Mendelsohn - famed for its "union busting" efforts at other big corporations - as an advisor. Regional managers have turned up at the Buffalo cafes "without warning" - including Starbucks' president for North America, Rossann Williams - and held "anti-union" focus groups on company time, it is claimed.

It has left would-be union representatives feeling "spied on" as they try to sign colleagues up during break times, the only time they're permitted to do so.

"What most companies do is make this a vote not about whether you want a union but whether you want to keep your job," says Richard Bensinger of Workers United, the union with which the baristas hope to affiliate. "They dominate the campaign."

Starbucks categorically denies the claims of spying, saying it holds around 2,000 listening sessions - or "Partner Open Forums" - a year and that it's not unusual for senior leaders to show up at cafes to discuss worker concerns.

"Our leaders are in the market to listen and take action to address the concerns of our partners. We are pro-partner, not anti-union," a spokesman says.

The firm is also one of the more generous and socially progressive in the US services sector - something the baristas acknowledge. It offers perks like free university tuition for staff, and in 2018, closed all its cafes to conduct racial bias training.

Yet while Starbucks says it respects the baristas' right to organise, the company also said it feels that it is "unnecessary" for them to unionise given its "outstanding" compensation and benefits.

Getty Images

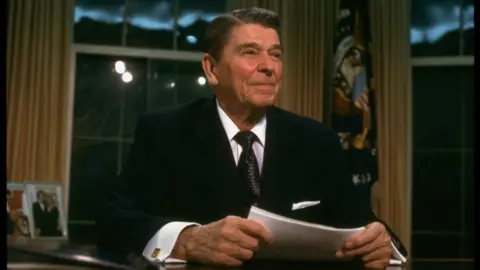

Getty ImagesRich history

The US has a rich history of labour organising dating back to the industrial revolution, and by the late 1960s more than a third of all US workers were union members. But that began to decline in the 1970s as manufacturing - the traditional backbone of US labour - moved offshore, and the Republican party under Ronald Reagan turned against unionism.

Many Republican states have since brought in "right to work" laws that weaken unions, while increasingly large corporations use their "vast resources" to quell organising efforts, says Dan Cornfield, an expert in unionism at Vanderbilt University.

But things are changing, he says.

Last year, the union membership rate edged up for the first time in years to 10.8%, while Gallup estimated 65% of all Americans approved of unions, the highest in over two decades.

Dr Cornfield says the election of Joe Biden - who has promised to be "the most pro-union president you've ever seen" - has brought organised labour back into the mainstream, while a "new vanguard" of younger educated professionals is driving change.

Allow X content?

"Unionism is not just for blue collar workers anymore," he says. "Younger workers in the service sector and some white collar occupations are calling for greater transparency from their employers, not just on pay but also issues like sexual harassment and racial justice."

Recent examples include the disgruntled Google engineers who unionised in January; a wave of successful campaigns at non-profit organisations such as the American Civil Liberties Union; and a new nurses' union at the Mission Hospital in North Carolina, one of the most anti-union states in the US.

The pandemic has put a fire under such efforts, after workers were abruptly laid off or had their hours or pay cut. Concerns about Covid safety measures also spurred walkouts at major names like McDonalds, Fiat Chrysler and the retailer Target.

"The pandemic showed workers that their very lives depended on having their own voice," says Mr Bensinger.

Reuters

ReutersSome of the newly unionised have already seen pay rises. Yet not all recent campaigns have succeeded. In April, Amazon easily defeated the first ever attempt to unionise one of its warehouses, in Bessemer, Alabama, with about 1,800 (71%) of workers voting against.

The shopping giant said it had listened to staff concerns and improved. It had also warned workers that the union would collect hundreds of dollars in dues without being able to deliver changes.

The NLRB has ordered a rerun after complaints of foul play by Amazon, but Gary Burtless of the Brookings Institution says "the vote totals do not suggest the union organisers were remotely close to winning".

He doesn't expect a big shift towards unionism, saying most low-paid workers still prefer unions "in theory" rather than practice. Mr Biden also lacks strong enough working majorities in the House and Senate "to expect much action at the federal level," Mr Burtless says.

In March, the House of Representatives passed the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, a sweeping pro-union bill backed by the President, which would change the rules around union elections and stiffen penalties for employers who violate workers' rights.

It comes after big firms - including Starbucks - were found to have illegally retaliated against employees who attempted to unionise.

Yet the PRO Act remains stalled in the Senate, along with attempts to raise the federal minimum wage to $15.

Allow X content?

The Buffalo baristas are undeterred and have received support from Starbucks workers across the US, as well as politicians such as congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the left-wing star of the Democratic party.

William Westlake, another member of the Buffalo organising committee, is sure unionism will grow.

"I think as we see increasing generational inequality then we're naturally going to see more of a fight to improve outcomes for the same entry level positions," he says.