How your personal data is being scraped from social media

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow much personal information do you share on your social media profile pages?

Name, location, age, job role, marital status, headshot? The amount of information people are comfortable with posting online varies.

But most people accept that whatever we put on our public profile page is out in the public domain.

So, how would you feel if all your information was catalogued by a hacker and put into a monster spreadsheet with millions of entries, to be sold online to the highest paying cyber-criminal?

That's what a hacker calling himself Tom Liner did last month "for fun" when he compiled a database of 700 million LinkedIn users from all over the world, which he is selling for around $5,000 (£3,600; €4,200).

The incident, and other similar cases of social media scraping, have sparked a fierce debate about whether or not the basic personal information we share publicly on our profiles should be better protected.

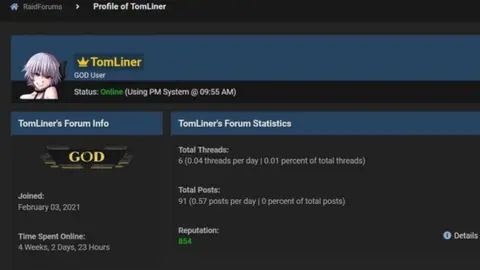

In the case of Mr Liner, his latest exploit was announced at 08:57 BST in a post on a notorious hacking forum.

It was a strangely civilised hour for hackers, but of course we have no idea which time zone, the hacker who calls himself Tom Liner, lives in.

"Hi, I have 700 million 2021 LinkedIn records", he wrote.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIncluded in the post was a link to a sample of a million records and an invite for other hackers to contact him privately and make him offers for his database.

Understandably the sale caused a stir in the hacking world and Tom tells me he is selling his haul to "multiple" happy customers for around $5,000 (£3,600; €4,200).

He won't say who his customers are, or why they would want this information, but he says the data is likely being used for further malicious hacking campaigns.

The news has also set the cyber-security and privacy world alight with arguments about whether or not we should be worried about this growing trend of mega scrapes.

What's important to understand here is that these databases aren't being created by breaking into the servers or websites of social networks.

They are largely constructed by scraping the public-facing surface of platforms using automatic programmes to take whatever information is freely available about users.

In theory, most of the data being compiled could be found by simply picking through individual social media profile pages one-by-one. Although of course it would take multiple lifetimes to gather as much data together, as the hackers are able to do.

NurPhoto

NurPhotoSo far this year, there have been at least three other major "scraping" incidents.

In April, a hacker sold another database of around 500 million records scraped from LinkedIn.

In the same week another hacker posted a database of scraped information from 1.3 million Clubhouse profiles on a forum for free.

Also in April, 533 million Facebook user details were compiled from a mixture of old and new scraping before being given away on a hacking forum with a request for donations.

The hacker who says he is responsible for that Facebook database, calls himself Tom Liner.

I spoke with Tom over three weeks on Telegram messages, a cloud-based instant messenger app. Some messages and even missed calls were made in the middle of the night, and others during working hours so there was no clue as to his location.

The only clues to his normal life were when he said he couldn't talk on the phone as his wife was sleeping and that he had a daytime job and hacking was his "hobby".

Tom told me he created the 700 million LinkedIn database using "almost the exact same technique" that he used to create the Facebook list.

He said: "It took me several months to do. It was very complex. I had to hack the API of LinkedIn. If you do too many requests for user data in one time then the system will permanently ban you."

API stands for application programming interface and most social networks sell API partnerships, which enable other companies to access their data, perhaps for marketing purposes or for building apps.

Tom says he found a way to trick the LinkedIn API software into giving him the huge tranche of records without setting off alarms.

Privacy Shark, which first discovered the sale of the database, examined the free sample and found it included full names, email addresses, gender, phone numbers and industry information.

LinkedIn insists that Tom Liner did not use their API but confirmed that the dataset "includes information scraped from LinkedIn, as well as information obtained from other sources".

It adds: "This was not a LinkedIn data breach and no private LinkedIn member data was exposed. Scraping data from LinkedIn is a violation of our Terms of Service and we are constantly working to ensure our members' privacy is protected."

In response to its April data scare Facebook also brushed off the incident as an old scrape. The press office team even accidentally revealed to a reporter that their strategy is to "frame data scraping as a broad industry issue and normalise the fact that this activity happens regularly".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, the fact that hackers are making money from these databases is worrying some experts on cyber security.

The chief executive and founder of SOS Intelligence, a company which provides firms with threat intelligence, Amir Hadžipašić, sweeps hacker forums on the dark web day and night. As soon as news of the 700 million LinkedIn database spread he and his team began analysing the data.

Mr Hadžipašić says the details in this, and other mass-scraping events, are not what most people would expect to be available in the public domain. He thinks API programmes, which give more information about users than the general public can see, should be more tightly controlled.

"Large-scale leaks like this are concerning, given the intricate detail, in some cases, of this information - such as geographic locations or private mobile and email addresses.

"To most people it will come as a surprise that there's so much information held by these API enrichment services.

"This information in the wrong hands could be significantly impacting for some," he said.

Tom Liner says he knows his database is likely to be used for malicious attacks.

He says it does "bother him" but would not say why he still continues to carry out scraping operations.

Mr Hadžipašić, who is based in southern England, says hackers who are buying the LinkedIn data could use it to launch targeted hacking campaigns on high-level targets, like company bosses for example.

He also said there is value in the sheer number of active emails in the database that can be used to send out mass email phishing campaigns.

'No ambiguity'

But cyber-security expert Troy Hunt, who spends most of his working life poring over the contents of hacked databases for his website haveibeenpwned.com, is less concerned about the recent scraping incidents and says we need to accept them as part of our public profile-sharing.

"These are definitely not breaches, there's no ambiguity here. Most of this data is public anyway.

"The question to ask, in each case though, is how much of this information is by user choice publicly accessible and how much is not expected to be publicly accessible."

Troy agrees with Amir that controls on social network's API programmes need to be improved and says we can't brush off these incidents.

"I don't disagree with the stance of Facebook and others but I feel that the response of 'this isn't a problem' is, whilst possibly technically accurate, missing the sentiment of how valuable this user data is and their perhaps downplaying their own roles in the creation of these databases."

Mr Liner's actions would be likely to get him sued by social networks for intellectual property theft or copyright infringement. He probably wouldn't face the full force of the law for his actions if he were ever found but, when asked if he was worried about getting arrested he said "no, anyone can't find me" and ended our conversation by saying "have a nice time".