Can better tech make video meetings less excruciating?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn most video conference calls, only one person gets to speak at a time. It's a deliberate, designed feature of platforms such as Zoom.

But as Susan D Blum's linguistic anthropology class found out, it makes having a natural conversation practically impossible.

"We always read transcripts out loud," she says, referring to her students at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana. The class exercise involves reading different parts of a dialogue together, exactly as they were spoken. That means overlapping at the end of some sentences, just like in casual conversation.

The problem is that Zoom, and other tools like it, only amplify one speaker's voice at a time - a deliberate feature of these platforms.

"You literally cannot have this kind of conversational overlap," says Prof Blum. "[The transcript readings] never worked at all."

Lionel Jensen

Lionel JensenMany people trying to have real conversations remotely have also found that chatter just didn't flow as smoothly as it does in face-to-face discussions.

Remote working will likely remain in place for some time, at least to some extent. So, will the technology that facilitates working from home improve?

A spokeswoman for Zoom says the platform uses various innovations to help meetings flow well, including noise suppression technology that removes background sounds, such as typing and paper rustling, or even dogs barking, to improve the audio.

But there are all sorts of other niggles with work-related virtual gatherings.

Sometimes people have mishaps on camera, connection issues cause disruption, and participants' body language may be difficult, or impossible, to read.

Research from the Institute for the Future of Work (IFOW) suggests that meeting via video has had benefits as well as downsides. On the one hand, sometimes workers have found it easier to keep track of, and join, meetings ad hoc.

On the other hand, video calls have sometimes made employees feel uncomfortable, especially those who are new to the company.

"This is not always as conducive to learning and training of younger members who aren't as confident to speak-up," says Abby Gilbert, principal researcher at IFOW. It means that good management and interpersonal skills are even more important for video meetings, she adds.

Technology can't replace those things but perhaps it can level the virtual playing field a bit.

The problem cited by Prof Blum, of unnatural audio, is one targeted by the app, High Fidelity, for instance. The app allows all participants on a call to speak at once and the software positions each speaker at a specific point along the stereo spectrum, from left to right.

The net effect is that the app can make it sound a bit like everyone is in the same room, it is most discernible when using headphones.

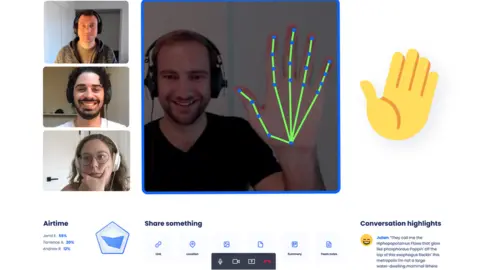

Another company that hopes to address the problems with online meetings is Headroom. Its platform, not yet publicly available, layers video calls with a suite of features intended to help participants read one another better.

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools in the software monitor people's faces and body language while they are on the call. The aim is to automatically alert the current speaker to gestures such as a raised hand (which suggests that someone would like to comment).

Headroom

HeadroomThe system can also quantify the "airtime" used by each participant, revealing who is dominating and who is hanging back, for instance. And speakers will even receive information about how engaged their audience is.

To do this, Headroom intends to constantly analyse the facial expressions of listeners on the call, among other things.

In-person meetings are, generally, much smoother than those online, says co-founder and chief executive, Julian Green.

"You can tell when people are with you because they're leaning in or nodding, or they're sort of in sync with you," he says. And you may find it easier to judge when to let someone else speak as a result of these subtle cues.

Emotion-detecting AI though is a controversial field because some previous systems have proved inaccurate, for example, or biased when reading the faces of non-white people.

Mr Green's fellow co-founder and chief technology officer Andrew Rabinovich acknowledges that building emotion-detecting AI is difficult but he argues that using multiple data sources - what people are typing as well as their facial expressions, for instance - can improve the overall accuracy of the system. This, the pair suggest, can give a broad sense of how engaged the audience is.

However, even such broad tracking will raise concerns about systems that monitor workers, which some call workplace surveillance.

Workplace surveillance has become more commonplace thanks to advances in technology and a rise in people working from home during the pandemic, according to a blog published last year by Dan Lucy at the Institute for Employment Studies.

"It also provides fertile ground for organisations and HR professionals to make poor decisions, damaging their reputation as an employer and place of work," he writes.

Another firm planning to launch emotion-detecting technology for meetings is Docket, which offers a range of tools to help workers plan agendas and take notes during video meetings.

Docket

Docket"That, we definitely believe, is going to be key to making that virtual meeting experience even more well rounded," says director of product Heather Hansson.

Will our meetings look more like video games?

Sharpening the productivity of meetings might be desirable. But it raises a question - just how well-oiled do we want all of our personal interactions with colleagues to be?

Many people working from home during the pandemic have missed informal chats and the casual office milieu. It's hard to replicate that in a video meeting.

But there could be another way. Video game-like platforms that allow employees to hang out online offer an opportunity for impromptu interactions.

Gather Town allows colleagues to spend time with one another "like you would in real life". In this case, that means socialising in a 2-D game world where your avatar can walk around and choose to meet specific colleagues - simultaneously via video chat - in small groups, rather than getting lumped in with everyone at once.

Enter Agora

Enter AgoraThen there is Enter Agora. It offers a 3-D virtual space that people can explore, mingle in, and attend more formal events such as meetings and presentations.

Chief executive Ruxandra Radulescu says that five clients, including a major law firm and a construction company are currently using the software.

The construction company, for instance, asked for specific locations from their headquarters to be replicated digitally in Enter Agora.

"You can have conversations with your colleagues as they land in the environment - the incidental conversations that you don't get to have otherwise," says Ms Radulescu.

I express some scepticism that people will want to spend much time in a video game version of their workplace. She says that, for quick meetings, a phone call or video chat may be preferable.

However, she also argues that Enter Agora can allow employees to feel a greater sense of togetherness when they are not able to travel to an event or office. Reducing the number of flights business people take could have environmental benefits, too.

Ms Radulescu asserts that people in the future will think it strange that such platforms weren't always an option.

"I see it 10 years from now… 'Do you remember when this happened? Wow, we used to have conversations in Zoom'," she says.