The codes helping visually-impaired people shop

A new, colourful kind of barcode technology, developed by a Spanish firm, is being adopted for the first time in food packaging in the UK.

It aims to help blind and partially-sighted people identify products in shops, and access health and safety information about food.

"I generally don't go shopping anymore because I can't do it without any kind of help," explains Beth Fowler, who is 19 years-old. "Because I can't see, practically… most things."

She is a pupil at St Vincent's School in Liverpool, a specialist school for people with sensory impairment.

"Shopping in supermarkets is a complete and utter pain," adds Marcia Shaw, 20, a recent graduate from the school, who is sight-impaired too. The store layouts keep changing, and you have to get help from assistants to find what you need, she explains.

But new technology is being rolled out that may help provide a solution to some of these problems.

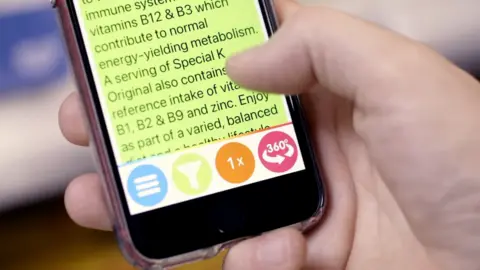

The school has been taking part in a trial with cereal manufacturer Kellogg's. The company has been testing out colourful barcodes on its packaging that mobile phone cameras can easily pick up using an app.

Normal barcodes, or QR codes, can be challenging for blind and partially-sighted people, because it takes a lot of dexterity to focus and frame them correctly, at close range, on a phone's camera.

These colourful ones can be detected at a distance of up to three metres, and in low-light conditions.

NaviLens

NaviLensThe technology is developed by a company from Murcia, Spain called NaviLens.

Its codes are already in use in Spain across public transport networks and museums. The New York City Subway system also uses it. Heathrow Airport in London began a trial, but this was postponed due to the pandemic.

All Kellogg's cereal packets will eventually display the code, starting with Special K cereal in January.

NaviLens

NaviLens"With the new app I can just pick the food off the shelf and scan it," explains Beth, "and read all the information, like ingredients, for example. Everything that a sighted person could see is made accessible."

Many pupils at St Vincent's School also have food allergies, explains Dianne Waites, who teaches Braille and assistive technology at the school, so this technology is even more vital for them.

Braille is a universal language that relies on physical touch, text is read by running your fingers over indentations on a surface. These indentations can be embossed on to food packaging, but take up a lot of space to convey limited information.

Only around 10% of blind and visually impaired people actually use Braille, according to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB).

All medicines in the UK must have the name of the medicine displayed in Braille on the labelling, and patient information leaflets must be available to the blind and partially sighted. But at the moment the vast majority of food products don't have Braille on their packaging, and there is no legal or regulatory requirement for them to include it.

NaviLens

NaviLensBecause the NaviLens digital codes trigger audio notes, the amount of information that can be conveyed is potentially limitless.

In addition to allergy warnings - like traces of nuts and the presence of gluten - the full range of information about ingredients, like fat and glucose composition, for example, can also be offered.

This kind of information can already be accessed across all products if you are shopping online - however when you are choosing products in a physical shop on the High Street, it's a different matter - customers also want to access the information at home when cooking.

There are a few other technologies already on the market aiming to address similar problems.

Google's Lookout app uses Artificial Intelligence to identify products through image recognition. This means no barcode or similar marker is necessary on the product packaging itself, but results are not perfect.

Meanwhile, Supersense, developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), is an app that reads out in a computer voice any text that you hover the camera over, and it can also read standard barcodes on food packages.

And Be My Eyes allows users to call volunteers for assistance, who can describe in real time what they see in front of them on a video call.

In 2018, Procter & Gamble introduced tactile markings on its Herbal Essences products so that people can distinguish between shampoo and conditioner. Sure deodorants, manufactured by Unilever, introduced Braille labelling this year.

Breakfast-only solution

However, with a proliferation of technologies companies may choose to invest in very different solutions, meaning a confused picture for consumers. So, for now, those who download the NaviLens app will find it only helps them fill a small but important part of their shopping basket - breakfast.

The RNIB surveyed its members and found that more than 95% want more assistive technology on products that can be accessed through phones.

"I describe my mobile phone as my Swiss Army Knife," explains Marc Powell, strategic accessibility lead for the RNIB, who is registered blind.

He says his phone allows him to access all kinds of information which he struggled to get hold of before, from bus timetables to courier delivery arrival times.

"There hasn't been technology available before that provides this amount of information all at once," he says.

"Standards need to start to change, we all have equal rights to access information, to independence. Technology is playing its part in making that happen."

Beth at St Vincent's school agrees it would make a really big difference to her life if the technology was adopted more widely.

"If we put accessible labels on bleach and medication, why shouldn't they be on food?" she says. "They can't put Braille on everything, but with these barcodes, it shouldn't be a massively difficult thing."

You can follow business reporter Dougal Shaw on Twitter: @dougalshawbbc