UK economy picks up as lockdown restrictions ease

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK economy shrank by 1.5% in the first three months of 2021, but gathered speed in March as lockdown restrictions began to ease, official figures show.

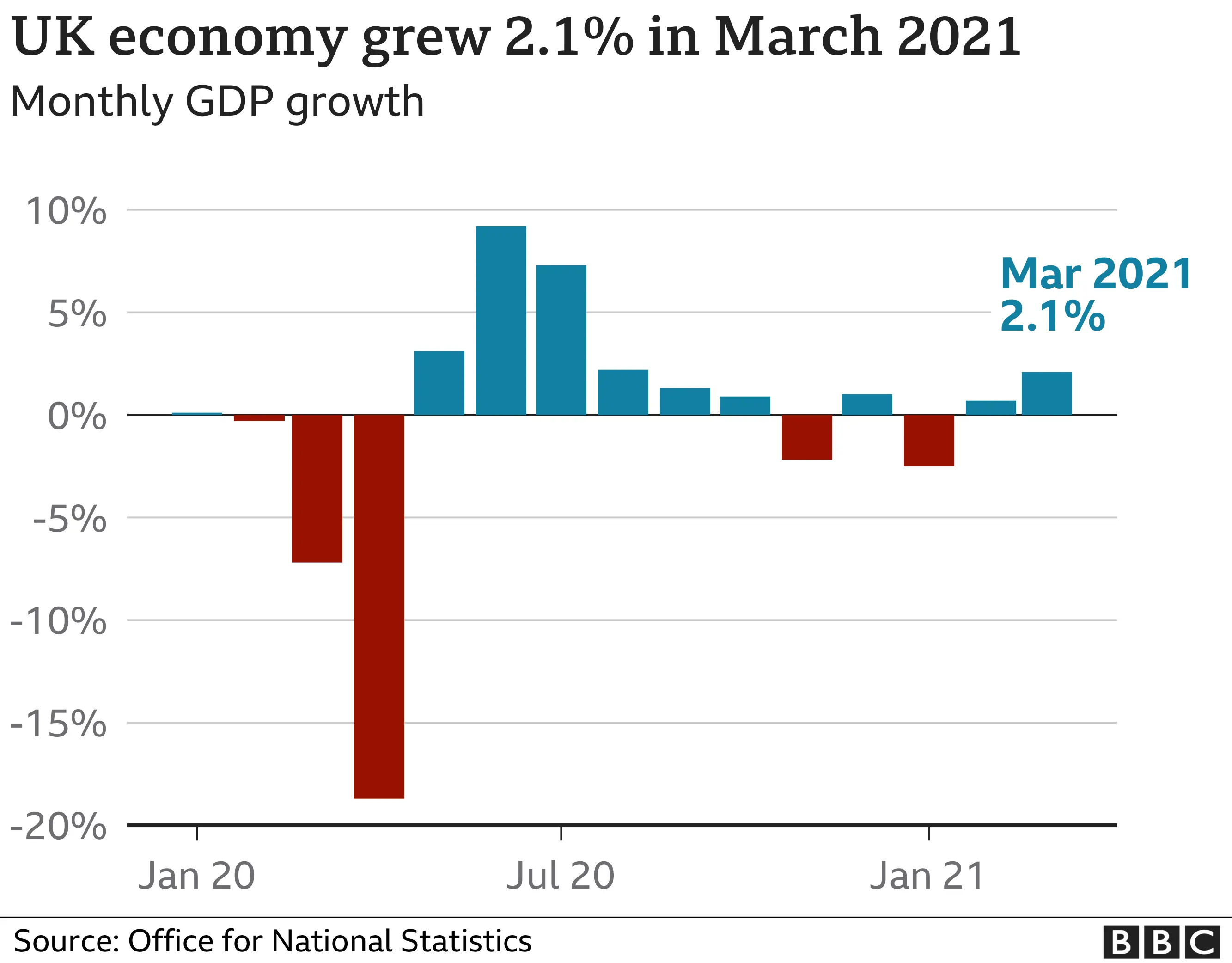

The reopening of schools and strong retail spending helped the economy grow 2.1% in March, its fastest monthly growth since last August.

But the economy is still 8.7% smaller than it was before the pandemic.

However, March marked a possible turning point, economists suggested.

Tej Parikh, chief economist at the Institute of Directors, predicted the UK economy was now on course for a bumper bounce-back this year.

"The first quarter should mark the low point for the economy in 2021," said Mr Parikh. "The lockdown, and added costs of navigating new trading terms with the EU, limited many businesses' trading activities at the start of the year."

What happened in the first three months of the year?

The UK economy suffered a record annual slump in 2020 as coronavirus restrictions hit output and 2021 started off equally downbeat.

The reintroduction of restrictions in January led to a fall in business investment and household consumption expenditure, according to the ONS.

However, schools reopening on 8 March triggered an uplift in retail sales and sectors such as construction and manufacturing remained resilient, growing strongly in March.

Businesses also continued to adapt and make themselves Covid secure.

Are things going to get better?

The vaccine rollout, the extension of support measures at the Budget, and the roadmap to reopen the economy have led to expectations that the UK economy will rebound strongly this year.

But there are concerns about long term damage.

Suren Thiru, head of economics at the British Chambers of Commerce, said: "The first quarter decline should be followed by a robust rebound in the second quarter as the effects of the release of pent-up demand, as restrictions ease and the strong vaccine rollout, are fully felt.

"However, with the longer-term economic damage caused by coronavirus likely to increasingly weigh on activity as government support winds down, the recovery may be slower than many, including the Bank of England, currently predict."

Alpesh Paleja, lead economist at the CBI, said that households and businesses have adapted better to working and living under Covid restrictions "despite the brutal cost of doing so".

But Pantheon Macroeconomics economist Samuel Tombs pointed out that the UK's economic growth was still the slowest of the Group of Seven (G7) rich countries, for the fourth quarter in a row.

GDP looks on course to grow by 5% between April and June "which should mean that the UK finally hands over the wooden spoon to another G7 economy", he added.

What do policymakers say?

On Wednesday, Chancellor Rishi Sunak told the the BBC the economy was "getting back on track".

"Despite a difficult start to this year, economic growth in March is a promising sign of things to come," he added.

Earlier this month, the Bank of England said it expected the UK economy to enjoy its fastest growth in more than 70 years this year, as restrictions are lifted.

But it cut its forecast for 2022 from 7.25% to 5.75%, suggesting the government was likely to raise taxes to pay for its huge pandemic-support programmes.

What's going on with trade?

Official trade figures, published at the same time as growth figures, showed a shift away from trading with EU countries since Brexit.

"Imports from Europe remained sluggish in the first three months of the year, being outstripped by non-EU imports for the first time on record," said ONS director of economic statistics Darren Morgan.

New Brexit trading rules between the EU and the UK came into effect at the beginning of January.

In the January to March quarter, the UK's exports to the EU fell 18.1% to £32.2bn, while exports to non-EU countries rose by 0.4% to £41.1bn, compared with the previous quarter.

The value of imports from the EU fell by 21.7% to £50.6bn, and imports from non-EU countries fell by 0.9% to £53.2bn.

The ONS said the UK's total trade deficit, excluding precious metals, narrowed by £8.4bn to £1.4bn.

Mr Sunak told the BBC the government has invested "hundreds of millions of pounds to help businesses adjust to those new trading arrangements and support them in the process".

"We've always said there will be a period of adjustment and that's what you're seeing," he added.

Why is there still uncertainty?

In ordinary times a 1.5% quarterly hit would be considered a considerable economic fall. In context of a further national shutdown, it shows some resilience in the UK economy.

Businesses, particularly manufacturing and construction, were beginning to work out how to cope with pandemic restrictions. The good news is that by the end of the quarter the rebound was starting.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak is not getting carried away with euphoria about the fastest growth in decades. The Treasury is well aware that this is mostly the arithmetic consequence of the bounce back from a sharp hit in 2020.

The ONS showed that the economic hole in the UK caused by the pandemic still does not compare favourably with other major economies, with the US, for example, having recovered all lost output.

Mr Sunak points to the much better than expected unemployment figures as the result of the furlough scheme. There is still uncertainty about how the global economy will respond to new waves of the pandemic. The chancellor is not changing the plan for tax rises on business.