Covid: The vaccine patent row explained

Reuters

ReutersWhen it comes to the pandemic, if there's anything world leaders agree on it's that no one is protected until everyone is.

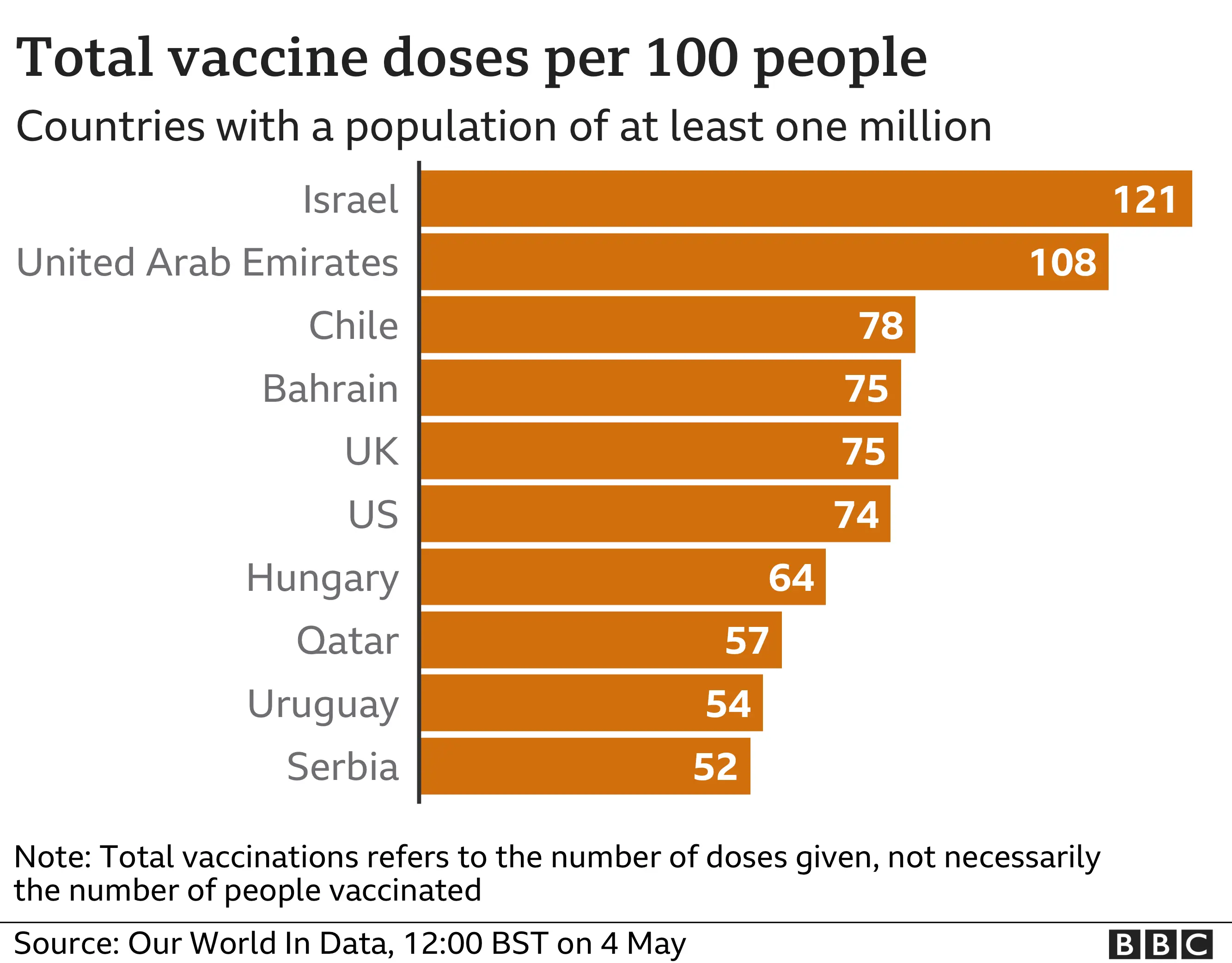

But they are struggling to agree on how to boost vaccine production amid a huge difference between vaccination rates in advanced and poorer nations.

This week, the US voiced its support for a temporary lift on the patents on vaccinations. But some countries have pushed back, insisting there are better options.

What is the row about?

Medicines and other inventions are covered by patents which provide legal protection against being copied, and vaccines are no exception.

Patents give makers the rights to their discoveries as well as the means to make more money from them - which is an incentive to encourage innovation.

But these are not normal times.

Last autumn, developing nations led by India and South Africa proposed to the World Trade Organization (WTO) that the patents on vaccinations and other Covid-related items should be waived.

They argued that, given the extreme nature of the pandemic, the recipe for the life-saving jabs should be made widely available so they could be produced locally in bulk by other manufacturers.

What's the problem?

The proposals were met with immediate criticism from pharmaceutical companies and Western nations including the EU, UK and - at that point - the US.

Most of the costs involved in coming up with vaccines are incurred in research and development: the manufacturing bit tends to cost less.

The obvious objection to lifting patents is that it could erode revenue and deter innovation.

So, does this just come down to money?

No. The waiver would be temporary - and some vaccine makers like AstraZeneca are offering doses at cost.

The key argument from vaccine producers and their home countries is that waiving patents alone wouldn't solve much. It would, they say, be like handing out a recipe without the ingredients or instructions.

The patent covers the bare bones of the blue print but not the precise production process. That's crucial here. Vaccines of the mRNA type - such as Pfizer and Moderna - are a new breed and only a small number of people understand how to make them.

BioNTech, the German company which partnered with Pfizer, have said that developing the manufacturing process took a decade and validating production sites can take up to a year. The availability of the raw materials needed has also been an issue.

Industry bodies fear that without access to all the know-how and parts, a waiver could result in quality, safety and efficacy issues and possibly even counterfeits. They point out that Moderna has already said it would not prosecute those found to be infringing their patent - but no one has yet.

What's the alternative?

The EU says it is ready to talk, but it previously said the best short-term fix would be supply chain improvements and pushing richer countries to export more jabs.

The UK says it is one of the biggest donors to Covax, which is masterminding the rollout of vaccines to many poorer countries. It also favours voluntary licensing - such as collaborations between the Serum Institute of India and Oxford-AstraZeneca. It wants the WTO, which oversees the rules on global trade, to support more partnerships.

The WTO system allows for this licensing arrangement to go even further. Governments can impose compulsory licenses on vaccine makers, compelling them to share their know-how and overseeing the production process along the way. But those pharmaceutical companies would have to be compensated for doing so.

Why did the US change its mind?

The announcement came after the US Trade Representative Katharine Tai held meetings with the big vaccine makers in an effort to supercharge vaccine production.

But some trade specialists must have queried if the move might be a negotiating tactic, to persuade vaccine makers to cooperate to a greater degree with licensing, either voluntarily or for a reduced charge.

What happens next?

Now the discussions will continue at the WTO where decisions are made by consensus.

Without the backing of other key nations, the proposals may stall. But they may pave the way to a compromise that could boost production.

The key question is when - and by how much.