Why global tax talks are back on the agenda

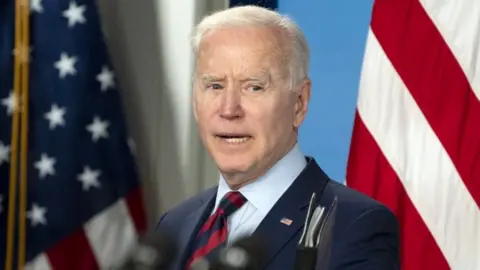

EPA

EPAInternational efforts to reform business taxation have been given new impetus by the new US administration.

Under President Joe Biden and his Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, the US has moved on two key areas where the negotiations were stuck.

One is having a minimum tax rate for corporate profits. The other is some exemptions on digital services taxes that the US had previously sought.

The goal of a global accord by mid-2021 now appears more credible.

The negotiations, co-ordinated through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), are building on previous work to reform corporate taxation.

The talks, which extend beyond the OECD's own member countries, are organised around what they call two pillars.

Both the issues have a bearing on all types of multinational business, but they are particularly acute in relation to some technology businesses.

The first is how to allocate profits, or revenue, between countries for taxing them.

Digital technologies make it so much more feasible to have a commercial relationship with a country, and make money from it, without any kind of physical presence.

So the debate is about ensuring that all types of business pay what a British government consultation paper called "a fair contribution to support our vital public services".

Going it alone

In the absence of an agreement in the OECD, some countries, including the UK, have gone ahead with their own digital services taxes.

The British one applies a 2% tax to the revenues (provided they exceed certain thresholds) derived from UK users of online marketplaces, social media and internet search engines.

The UK and some other countries have promised to discontinue the unilateral tax if there is an "appropriate" international agreement.

One of the factors impeding progress towards such a deal was the US's insistence on what was called a "safe harbour" provision. Critics described it as making the tax optional, a characterisation that Trump administration officials rejected.

But however it is described, the Biden administration has dropped the idea.

In fact, the US is reported by the Financial Times to have actively proposed a system in which multinationals would pay taxes based on their sales in each country - along the same general principles as the British and other unilateral taxes.

According to the FT, only very large firms would be subject to these tax arrangements under the US proposals.

That said, there are different, and rather complex, ideas under discussions in the negotiations. They would allocate profits beyond a certain baseline level to countries where the multinational company gets its revenue.

Profit shifting

The second pillar is a global minimum corporate tax rate. If that were applied widely enough, it would weaken the incentive that multinational companies have to shift their profits to places where the tax rate is lower.

The Trump administration opposed this. Now the US is in favour. Ms Yellen has said it would end what she called a race to the bottom, to see who can lower their corporate tax rate further and faster.

Why has the US position changed? The Biden administration's plans include a large programme of spending on infrastructure - traditional, such as roads, bridges and ports, and modern, such as broadband and clean energy.

The president and his Treasury secretary want to finance it to a large extent with higher rates of corporate tax. An international agreement could forestall efforts that other countries would be tempted to make, to entice American firms to choose them over the US.

There is a long history of international agreements on taxation. In the past, the aim tended to be to prevent "double taxation", the same income, personal or business, being taxed in twice in different jurisdictions.

More recent negotiations, including those in the OECD, have often had the opposite aim: the prevention of what has been called "double non-taxation".