Economic outlook 'unusually uncertain' despite 'rapid' vaccine rollout

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe outlook for the UK economy remains "unusually uncertain" despite the rapid rollout of the vaccine programme, the Bank of England has said.

It said it expected an economic rebound this year, as lockdown measures were eased and government support for jobs continued.

But it said the recovery still depended on the "evolution of the pandemic" and measures to protect public health.

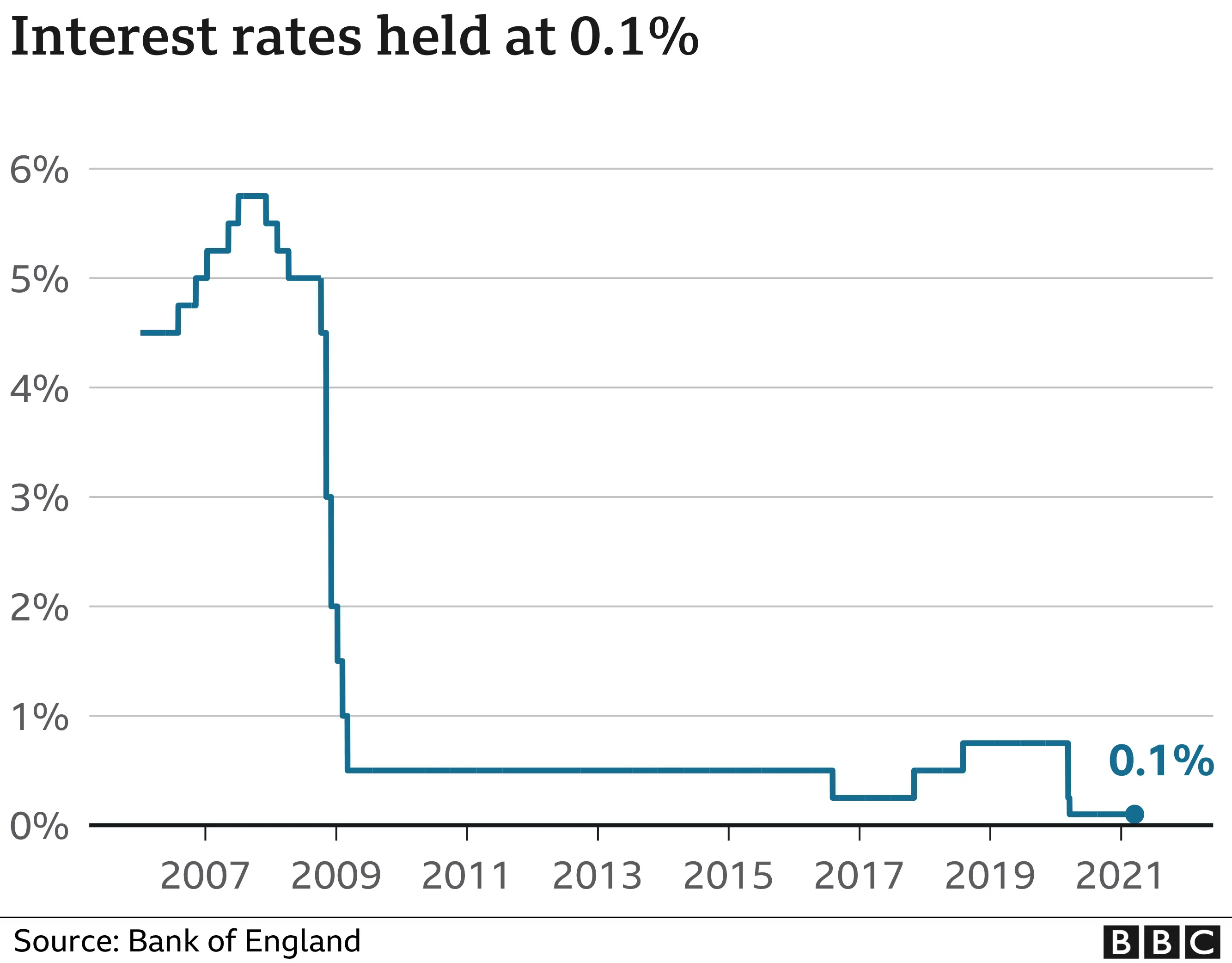

It came as the Bank held interest rates at historic lows of 0.1%.

According to official figures, the UK economy shrank by 2.9% in January amid the third lockdown, as restaurants and non-essential shops were shuttered.

But the drop was much smaller than expected, suggesting businesses have adapted to trading in lockdown.

It's added to growing expectations that the recovery will be stronger than previously expected, thanks in large part to the vaccine programme.

Despite concerns about supply, everyone above the age of 50 and all adults in risk groups are set to have their first jab by the end of May, followed by all adults by the end of July.

Last week, Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey told the BBC that he expected the economy to "get back at the end of this year to where it was at the end of 2019".

Meanwhile, the government's fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, forecasts that unemployment will peak at 6.5% instead of the 11.9% predicted last July.

Cautious tone

However, an official statement on Thursday from the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), which sets interest rates, was more cautious.

It said recent plans to ease lockdown "may be consistent with a slightly stronger outlook" in the near term, but it was unclear whether they would make a difference in the medium-term.

"The outlook for the UK economy, and particularly the relative movement in demand and supply during the recovery from the pandemic, remains unusually uncertain," it added.

"It continues to depend on the evolution of the pandemic, measures taken to protect public health, and how households, businesses and financial markets respond to these developments."

Silvia Dall'Angelo, senior economist at the International Business of Federated Hermes, said the cautious tone of the MPC's statement was in line with other central banks.

"The Bank of England is facing the same cross-currents. Since its previous meeting in February, most developments - notably fresh rounds of fiscal stimulus domestically and abroad - have had positive implications for the economic outlook, but downside risks and uncertainty concerning the evolution of the pandemic are still prominent."

There have been warnings that inflation could breach the Bank's 2% target this year, but Mr Bailey has played the threat down.

On Thursday, the MPC said it would continue to monitor the situation closely but had no immediate plans tighten monetary policy.

But it said if the outlook for inflation weakens, "the committee stands ready to take whatever additional action is necessary to achieve its remit".

On Wednesday, the US Federal Reserve also played down warnings of rising inflation, saying any increases above its own 2% target were likely to be "transient".

Today's Monetary Policy Report plays down the risk of a rate rise any time soon. And the BoE has more than one reason to do so.

The pandemic has brought weirdness to many of our lives. The same applies to the Bank of England. It continues to insist it doesn't engage in monetary financing, where the central bank simply creates money from nothing (once upon a time you could say "prints money" but now it's digital) and "lends" it to the government.

However, what's happening now is not much different. As the Financial Times has noted, of the money being borrowed by the government this financial year by issuing gilts - a sort of IOU note also known as a government bond - 92.7% of it will be owed to the Bank of England.

Not only is the government "borrowing" most of its money from another branch of the public sector. If it pays interest on that debt it gets it straight back. Easy money. But the money the BoE creates from nothing is used to buy gilts from big City players like pension funds, hoping they'll invest the cash in productive industry (the last 12 years by no means supports that hope).

What they get in exchange is BoE reserves, which pay interest at the official rate. So if rates rose, the BoE - underwritten by the Treasury - would be one of the biggest losers.