Amazon fight with workers: 'You're a cog in the system'

RWDSU

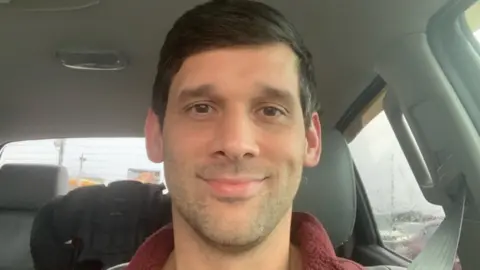

RWDSUJoseph Jones doesn't find the gruelling physical demands of his job at Amazon particularly troubling - he can walk as many as 17 miles per shift. The firm's attitude towards his work, however, is something else.

"It's a very adversarial relationship with the supervisors and the staff," says the 35-year-old, who started working part-time at the company's warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama in October. "You're a cog in the system... and it's very obvious."

During the busy season between Thanksgiving and Christmas, for example, he says Amazon required staff to extend their shifts - typically with little notice. Once, he says he didn't even know he had been asked to put in extra time until he arrived for work and the company app informed him he was an hour late.

Last year, the treatment prompted him to join a petition that sought an official vote on creating a union at the warehouse.

In December, state labour officials ruled the request had garnered enough support to warrant an election - the first such vote Amazon has faced in the US since 2014. Ballots were mailed this week.

If the campaign succeeds, the Bessemer facility, which opened in March, would become the only unionised Amazon location in the US.

Joseph Jones

Joseph JonesRWDSU campaign

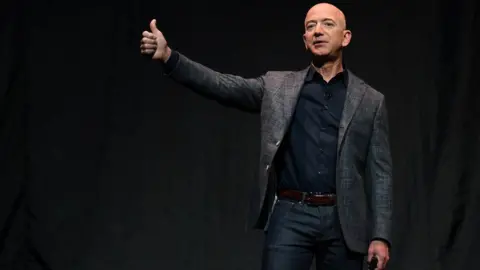

"This election takes on enormous importance because Amazon is not just another company," says Stuart Appelbaum, president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU), which is leading the effort. "This election transcends Bessemer. It's really about how workers are going to be treated in the future."

Organisers have spent months making their case to the nearly 6,000 people who work at the facility. They have lined the side of the road with signs, posted representatives at the plant's gates, hosted meetings and rallies, and spent hours "talking, talking, talking".

For its part, Amazon has responded with mandatory weekly meetings discouraging the proposal, plastered the warehouse with anti-union flyers, blasted text messages to staff, and launched a website "Do it without Dues", which promotes the firm's "high wages" - hourly pay starts at $15.30 (£11.15) - health benefits, and safety committee.

It also sought, unsuccessfully, to force the election to be held in person, rather than by mail, as officials required due to the pandemic.

Amazon spokeswoman Heather Knox says the company is "providing education" on the impact of a potential union - which it estimates would cost full-time staff $500 in dues - and does not believe the RWDSU "represents the majority of our employees' views".

"Our employees choose to work at Amazon because we offer some of the best jobs available everywhere we hire, and we encourage anyone to compare our total compensation package, health benefits, and workplace environment to any other company with similar jobs," she says, adding that the company has improved its safety measures since the start of the pandemic.

Reuters

ReutersAt the plant, Joseph says the pressure has been intense, with rumours flying about the firm's efforts to infiltrate workers.

"They're terrified of what precedent this could set," he says of the company.

Pandemic effect

For years, Amazon has been able to brush past complaints about its business practices and working conditions.

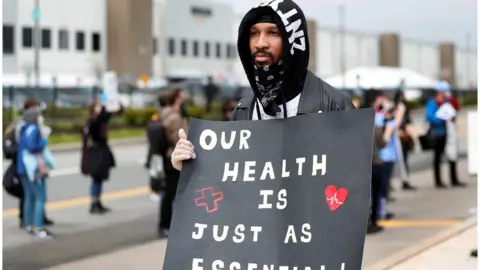

But the pandemic - which brought health risks alongside a surge in the firm's business and profit - has galvanised workers around the world. This is despite the firm's notoriously aggressive efforts to squelch labour activism, says Christy Hoffman, secretary general of UNI Global Union, which works with unions globally, including the RWDSU.

"Amazon's dynamics did not shift but the workers became much more active during the pandemic when the danger to them in connection with social distancing, the pace of work, the volume of work became so dangerous," she says.

Last year, the company was hit by strikes in Italy and Germany and protests at warehouses and grocery stores in the US. In France and Spain, unions lodged complaints with the state, leading to government intervention.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Bessemer, a majority black suburb of Birmingham, Alabama where a quarter of families live below the poverty line, tensions emerged amid last summer's Black Lives Matter protests.

Staff sought out the RWDSU. Mr Appelbaum says they wanted more information about co-workers falling ill and were upset by the "dehumanising" way they were managed - receiving unpredictable assignments from robots and getting disciplined via an app.

Other affronts came into play. In June, the firm abruptly ended hazard pay, an extra $2 per hour that it had offered at the start of the pandemic, even as virus cases continued to rage.

"Amazon's business is thriving and they do something as picky as taking away hazard pay from their employees," Joseph says. "I think it put a bad taste in everybody's mouth."

Will the campaign succeed?

The Birmingham area has a rich history of civil rights activism and unionisation, tied to its past as a coal mining and steel centre.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut unionisation rates have plunged in the US and in southern states, like Alabama, suspicion of organised labour runs deep. In Bessemer, a city of 27,000 hit hard by the departure of major manufacturers in the 1980s, Amazon's arrival was welcomed as a source of employment.

"The educated folks will tell you money's not a motivator. Well I guarantee you… money is a motivator and the biggest difference with Amazon is they pay," says labour leader Bren Riley, president of the Alabama AFL-CIO, of which the RWDSU is an affiliate. "They don't have problems getting people to come to work."

Alan Draper, the Ranger professor of government at St Lawrence University, says unions lose votes like the one facing Amazon much more than they did in the past.

"The sense of fear that employers are able to create is tremendous. That the union has been successful enough to get workers past that fear in order to get to an election is remarkable today," he says. "Unfortunately it's very episodic."

Reuters

ReutersIf the union wins, Amazon would be forced to negotiate over a contract, which could address anything from pay and holidays, to discipline and production expectations.

With ballots due on 29 March, the fight has attracted national attention. Liberal political stars in the US such as former presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders and Rep Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as well as the NFL Players Association, which represents American football players, have chimed in with support.

In Alabama, however, many politicians have steered clear of the fight.

"Whatever the differences are, I hope that they can be rectified to the satisfaction of the employees as well as to Amazon," says Bessemer Mayor Ken Gulley, a Democrat, who was part of a team that helped lure Amazon to town in 2018 with millions of dollars worth of state and local tax breaks.

RWDSU

RWDSUHe says he wants to see everyone "treated fairly" but worries that the high-profile union drive could hurt the city's efforts to attract other big employers like Amazon, whose economic impact he describes as "significant".

"Obviously it's a great company and we're looking to a strong partnership with them for many years to come."

Joseph says he's not sure how the vote will go, but is hopeful the Bessemer effort will inspire Amazon workers elsewhere to take a stand.

"If this is successful - knock on wood - then I hope everybody follows suit."