How Covid turbocharged the QR revolution

Duke's

Duke's"Our customers love it," says Michael Schatzberg, the co-founder of a US restaurant group.

He is talking about using QR codes (quick response codes), a technology from the 1990s, which is proving to be very useful in the Covid era.

Many restaurants have turned to the tech, which allows customers to see a menu, order and pay just by pointing their smartphone at the black, barcode-like squares.

"They don't have to wait. They can just pay and leave without asking for the bill," says Mr Schatzberg, whose restaurants include Duke's and Big Daddy's in New York.

QR codes were invented in Japan in the mid-90s to track components in car production.

They can hold a massive amount of data compared to standard barcodes - up to 2,500 numeric characters compared to a barcode's 43.

That means really useful information, including names, locations and website addresses can all be reliably and cheaply held in one small box.

And reports say that Apple could be giving the format an upgrade with dots, circles and colours, instead of the current blocks.

QR codes are enjoying their moment in the spotlight thanks to their ability to connect the digital world to the physical.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, many pubs and restaurants moved quickly to install QR code systems.

Branded Strategic Hospitality

Branded Strategic Hospitality"We saw how five years of a future technology was accelerating at a pace of five months," says Mr Schatzberg.

Pharmacies are also using QR codes. In the US, CVS is offering touch-free payments through a partnership with PayPal and Venmo at 8,200 stores.

The code is scanned during checkout, and customers simply open either the PayPal or Venmo mobile app and click the "Scan" button, then select the "Show to pay" option. Customers need to be PayPal or Venmo users, or they can pay using their debit and credit cards, or bank accounts.

The QR code checkout process pulls funds needed for the purchase from the customer's PayPal or Venmo account balance, bank account or from a debit or credit card, in a similar way to an online transaction.

Several start-ups are using the QR code for retail storefronts. Stockholm-based Ombori invented its Grid technology, which allows retailers to have a digital screen displaying QR codes, and offers passers-by the opportunity to purchase items right from the street after viewing photos and videos of them.

The system is used by firms in more than 24 countries, including clothes store H&M, Danish furniture chain BoConcept and hotel group Radisson Blu.

Andreas Hassellhof, founder and chief executive of Ombori, argues it is a good way for retailers to create extra online relationships with customers.

Getty Images

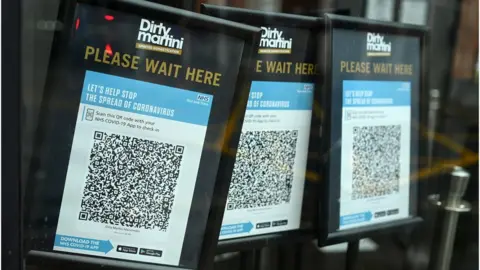

Getty ImagesPublic health agencies have also seen value in taking advantage of QR codes to assist with contact-tracing efforts.

In the UK, through the NHS, designated venues in certain sectors have a legal requirement to display NHS QR code posters so that customers with the NHS Covid-19 app can "check in" using this option as an alternative to providing their contact details to the venue.

If someone tests positive for Covid-19 at that venue, then other visitors to the location are alerted by an app thanks to the data accumulated from QR code scans.

The NHS notes the app will retain information about which users have frequented the location for 21 days.

QR codes are also being used for contact tracing in countries such as Australia, Singapore and South Korea.

Scanning food items and paying for them via QR codes is also trending, due to new technologies changing how we pay for everyday essentials. Grabango bills itself as "checkout-free technology", which will be familiar to anyone who uses Amazon Go.

Similar to Amazon's bricks-and-mortar stores, Grabango's technology allows grocery shoppers to simply take items off the shelf and leave without paying for them at the cashier. Instead, shoppers scan their unique QR code at a kiosk when they've finished shopping.

Grabango

GrabangoSo far, Grabango has secured a deal with Giant Eagle's supermarkets and convenience stores across the US.

"I don't see a reason why QR codes won't be pervasive in all of retail at some point in the future," says Andrew Radlow, chief business officer at Grabango.

Then there's the high-tech shopping cart that could usher in a new era of contactless shopping. Veeve's Smart Cart pairs shoppers with a QR code on their phone, which lets the store identify the individual shopper.

Placing items in the Smart Cart will add a tally to the trip's bill and then the shopper can head to a dedicated checkout lane where they only need to scan their QR code to make an automatic payment.

The system is currently being tested in two grocery stores, one in Seattle and one in California.

"Check-in is the new checkout," says Shariq Siddiqui, chief executive of Seattle-based Veeve. He credits the popularity of QR codes to their convenience. "They can give you the consumer a lot of control, as long as privacy concerns are met."

But privacy concerns still worry some, including Graham William Greenleaf, a professor of law and information systems at the University of New South Wales Sydney.

In his home country, his concerns revolve around "attendance tracking" technology enabled through QR codes so Australian companies can monitor capacity levels at their businesses. The innovation is also being used to help with contact tracing.

"These QR code systems have been established without any new protective legislation," he says, "in contrast with the strict privacy-protective 'CovidSafe Act' enacted to control the use of the CovidSafe app for Bluetooth-based proximity tracking. The solution to these problems lies with governments enacting protective legislation, not with the QR providers.

"Attendance tracking, a form of location surveillance, is a serious interference with privacy, and is only justified for so long as it is necessary for Covid-19 contact tracing. It must be terminated once no longer necessary."