Tax rises of more than £40bn a year 'all but inevitable'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTaxes rises of more than £40bn a year are 'all but inevitable' to protect UK government debt from spinning out of control, a think tank has warned.

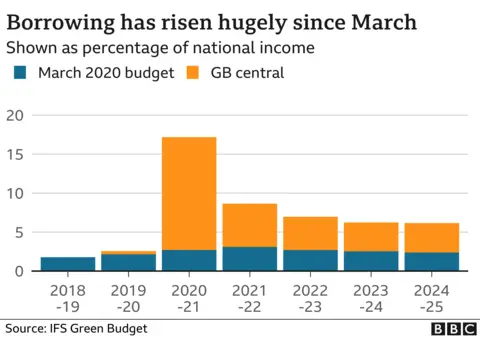

The Institute for Fiscal Studies said borrowing this year will hit levels not seen in peacetime due to the pandemic.

It said the state had pumped an extra £200bn into the economy to support jobs, businesses and incomes this year.

This was necessary but would mean big tax hikes into the middle of the next decade, the IFS said.

To pay for the services it provides, the UK government borrows from pension funds, insurance companies and investors around the world, then tries to balance its books through taxes.

But in an update originally meant to accompany the chancellor's now scrapped Autumn Budget, the IFS said this would become harder as the crisis rolled on.

It said the economy was forecast to be 5% smaller in 2024-25 than was projected back in March, which would leave the country with a £100bn hit to its finances from lower tax revenues.

At the same time, it said "higher borrowing will be with us for some time to come".

The government will not, as the chancellor promised just a week ago, "always balance the books" and the Conservative manifesto commitment on lower debt is impossible, says the Institute for Fiscal Studies in its annual audit of the public finances.

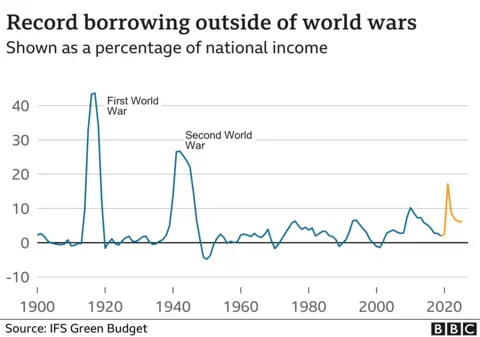

Annual government borrowing this year will reach levels only previously reached during world wars, while the national debt will be bigger than the economy, reaching 110% of GDP by 2025.

However, the IFS warns that now is not the time for tax rises or spending cuts. The economy will continue to need support because of one of the worst pandemic hits to growth in the world, alongside the prospect of new post-Brexit trade barriers with the EU.

For now, extra borrowing is helped by extraordinarily low rates of interest paid by the government. But the IFS outlines a scenario where even significant tax rises, worth £40bn a year from the middle of this decade, will fail to get the size of the national debt below 100% of GDP.

Repaying the Covid support spending is, the institute suggests, going to be a delayed and then very gradual programme of tax-and-spend restraint that could last a generation.

Paul Johnson, director of the IFS, said the government had no choice but to ramp up spending in the short term, and there was little it could do "fully to protect the economy into the medium run".

"We are heading for a significantly smaller economy than expected pre-Covid and probably higher spending too.

"Without action, debt - already at its highest level in more than half a century - would carry on rising. Tax rises, and big ones, look all but inevitable, though likely not until the middle years of this decade."

Reuters

ReutersThe UK's national debt - how much it owes investors and lenders - rose above £2 trillion for the first time in August.

The think tank said it expects debt will be just over 110% of national income by 2024-25. This would be up from 80% before the pandemic and 35% in the years leading up to the 2007-08 financial crisis.

The IFS said the UK had benefited from historically low interest rates during the crisis, which made it cheaper to borrow.

But it warned any increase in rates could, if not accompanied by stronger growth, be "hugely problematic for the public finances".

The forecast comes as the UK economy remains under stress. In an accompanying analysis, Citibank said every major economy bar China shrank in the first half of this year, mostly by historically large margins.

Spain and the UK did the worst, with output drops of roughly 20%, more than double the hit in the US or Germany.

The bank warned that even if another round of major lockdowns can be avoided, most economies will not return to pre-pandemic levels of output until 2021 or 2022.

And even when the pandemic is over, there will be lingering effects on consumer demand due to increased caution, shifts in behaviour and rising unemployment.

Citibank forecasts the unemployment rate in the UK is likely to increase to about 8% to 8.5% - or 2.7 to 2.9 million people out of work - in the first half of 2021.

That could see unemployment at its highest level since the early 1990s.